Container technology has, for many years, been transforming how workloads in data centers are managed and speeding the cycle of application development and deployment.

In addition, container images are increasingly used as a distribution format, with container registries a mechanism for software distribution. Isn't this just like packages distributed using package management tools? Not quite. While container image distribution is similar to RPMs, DEBs, and other package management systems (for example, storing and distributing archives of files), the implications of container image distribution are more complicated. It is not the fault of container technology itself; rather, it's because container distribution is used differently than package management systems.

Talking about the challenges of license compliance for container images, Dirk Hohndel, chief open source officer at VMware, pointed out that the content of a container image is more complex than most people expect, and many readily available images have been built in surprisingly cavalier ways. (See the LWN.net article by Jake Edge about a talk Dirk gave in April.)

Why is it hard to understand the licensing of container images? Shouldn't there just be a label for the image ("the license is X")? In the Open Container Image Format Specification, one of the pre-defined annotation keys is "org.opencontainers.image.licenses," which is described as "License(s) under which contained software is distributed as an SPDX License Expression." But that doesn't contemplate the complexity of a container image–while very simple images are built from tens of components, images are often built from hundreds of components. An SPDX License Expression is most frequently used to convey the licensing for a single source file. Such expressions can handle more than one license, such as "GPL-2.0 OR BSD-3-Clause" (see, for example, Appendix IV of version 2.1 of the SPDX specification). But the licensing for a typical container image is, typically, much more complicated.

In talking about container-related technology, the term "container" can lead to confusion. A container does not refer to the containment of files for storing or transferring. Rather, it refers to using features built into the kernel (such as cgroups and namespaces) to present a sort of "contained" experience to code running on the kernel. In other words, the containment to which "container" refers is an execution experience, not a distribution experience. The set of files to be laid out in a file system as the basis for an executing container is typically distributed in what is known as a "container image," sometimes confusingly referred to simply as a container, thereby awkwardly overloading the term "container."

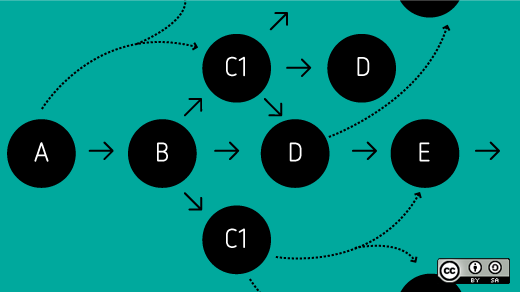

In understanding software distribution via container images, I believe it is useful to consider two separate factors:

- Diversity of content: The basic unit of software distribution (a container image) includes a larger quantity and diversity of content than in the basic unit of distribution in typical software distribution mechanisms.

- Use model: The nature of widely used tooling fosters the use of a registry, which is often publicly available, in the typical workflow.

Diversity of content

When talking about a particular container image, the focus of attention is often on a particular software component (for example, a database or the code that implements one specific service). However, the container image includes a much larger collection of software. In fact, even the developer who created the image may have only a superficial understanding of and/or interest in most of the components in the image. With other distribution mechanisms, those other pieces of software would be identified as dependencies, and users of the software might be directed elsewhere for expertise on those components. In a container, the individual who acquires the container image isn't aware of those additional components that play supporting roles to the featured component.

The unit of distribution: user-driven vs. factory-driven

For container images, the distribution unit is user-driven, not factory-driven. Container images are a great tool for reducing the burden on software consumers. With a container image, the image's consumer can focus on the application of interest; the image's builder can take care of the dependencies and configuration. This simplification can be a huge benefit.

When the unit of software is driven by the "factory," the user bears a greater responsibility for building a platform on which to run the software of interest, assembling the correct versions of the dependencies, and getting all the configuration details right. The unit of distribution in a package management system is a modular unit, rather than a complete solution. This unit facilitates building and maintaining a flow of components that are flexible enough to be assembled into myriad solutions. Note that because of this unit, a package maintainer will typically be far more familiar with the content of the packages than someone who builds containers. A person building a container may have a detailed understanding of the container's featured components, but limited familiarity with the image's supporting components.

Packages, package management system tools, package maintenance processes, and package maintainers are incredibly underappreciated. They have been central to delivery of a large variety of software over the last two decades. While container images are playing a growing role, I don't expect the importance of package management systems to fade anytime soon. In fact, the bulk of the content in container images benefits from being built from such packages.

In understanding container images, it is important to appreciate how distribution via such images has different properties than distribution of packages. Much of the content in images is built from packages, but the image's consumer may not know what packages are included or other package-level information. In the future, a variety of techniques may be used to build containers, e.g., directly from source without involvement of a package maintainer.

Use models

What about reports that so many container images are poorly built? In part, the volume of casually built images is because of container tools that facilitate a workflow to make images publicly available. When experimenting with container tools and moving to a workflow that extends beyond a laptop, the tools expect you to have a repository where multiple machines can pull container images (a container registry). You could spin up your own. Some widely used tools make it easy to use an existing registry that is available at no cost, provided the images are publicly available. This makes many casually built images visible, even those that were never intended to be maintained or updated.

By comparison, how often do you see developers publishing RPMs of their early explorations? RPMs resulting from experimentation by random developers are not ending up in the major package repositories.

Or consider someone experimenting with the latest machine learning frameworks. In the past, a researcher might have shared only analysis results. Now, they can share a full analytical software configuration by publishing a container image. This could be a great benefit to other researchers. However, those browsing a container registry could be confused by the ready-to-run nature of such images. It is important to distinguish between an image built for one individual's exploration and an image that was assembled and tested with broad use in mind.

Be aware that container images include supporting software, not just the featured software; a container image distributes a collection of software. If you are building upon or otherwise using images built by others, be aware of how that image was built and consider your level of confidence in the image's source.

Comments are closed.