In today's connected embedded device market, driven by the Internet of things (IoT), a large share of devices in development are based on Linux of one form or another. The prevalence of low-cost boards with ready-made Linux distributions is a key driver in this. Acquiring hardware, building your custom code, connecting the devices to other hardware peripherals and the internet as well as device management using commercial cloud providers has never been easier. A developer or development team can quickly prototype a new application and get the devices in the hands of potential users. This is a good thing and results in many interesting new applications, as well as many questionable ones.

When planning a system design for beyond the prototyping phase, things get a little more complex. In this post, we want to consider mechanisms for developing and maintaining your base operating system (OS) image. There are many tools to help with this but we won't be discussing individual tools; of interest here is the underlying model for maintaining and enhancing this image and how it will make your life better or worse.

There are two primary models for generating these images:

- Centralized Golden Master

- Distributed Build System

These categories mirror the driving models for Source Code Management (SCM) systems, and many of the arguments regarding centralized vs. distributed are applicable when discussing OS images.

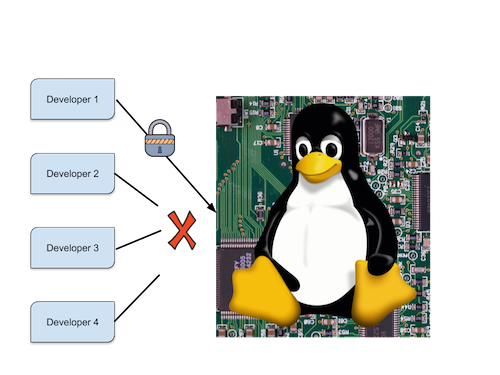

Centralized Golden Master

Hobbyist and maker projects primarily use the Centralized Golden Master method of creating and maintaining application images. This fact gives this model the benefit of speed and familiarity, allowing developers to quickly set up such a system and get it running. The speed comes from the fact that many device manufacturers provide canned images for their off-the-shelf hardware. For example, boards from such families as the BeagleBone and Raspberry Pi offer ready-to-use OS images and flashing. Relying on these images means having your system up and running in just a few mouse clicks. The familiarity is due to the fact that these images are generally based on a desktop distro many device developers have already used, such as Debian. Years of using Linux can then directly transfer to the embedded design, including the fact that the packaging utilities remain largely the same, and it is simple for designers to get the extra software packages they need.

There are a few downsides of such an approach. The first is that the golden master image is generally a choke point, resulting in lost developer productivity after the prototyping stage since everyone must wait for their turn to access the latest image and make their changes. In the SCM realm, this practice is equivalent to a centralized system with individual file locking. Only the developer with the lock can work on any given file.

The second downside with this approach is image reproducibility. This issue is usually managed by manually logging into the target systems, installing packages using the native package manager, configuring applications and dot files, and then modifying the system configuration files in place. Once this process is completed, the disk is imaged using the dd utility, or an equivalent, and then distributed.

Again, this approach creates a minefield of potential issues. For example, network-based package feeds may cease to exist, and the base software provided by the vendor image may change. Scripting can help mitigate these issues. However, these scripts tend to be fragile and break when changes are made to configuration file formats or the vendor's base software packages.

The final issue that arises with this development model is reliance on third parties. If the hardware vendor's image changes don't work for your design, you may need to invest significant time to adapt. To make matters even more complicated, as mentioned before, the hardware vendors often based their images on an upstream project such as Debian or Ubuntu. This situation introduces even more third parties who can affect your design.

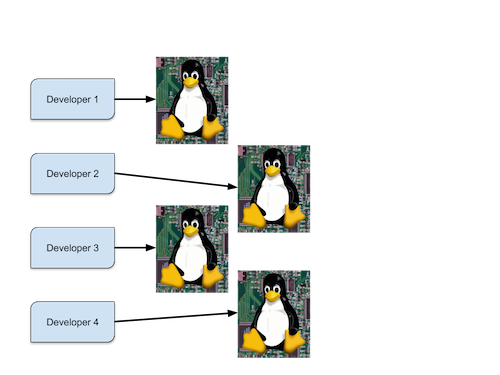

Distributed Build System

This method of creating and maintaining an image for your application relies on the generation of target images separate from the target hardware. The developer workflow here is similar to standard software development using an SCM system; the image is fully buildable by tooling and each developer can work independently. Changes to the system are made via edits to metadata files (scripting, recipes, configuration files, etc) and then the tooling is rerun to generate an updated image. These metadata files are then managed using an SCM system. Individual developers can merge the latest changes into their working copies to produce their development images. In this case, no golden master image is needed and developers can avoid the associated bottleneck.

Release images are then produced by a build system using standard SCM techniques to pull changes from all the developers.

Working in this fashion allows the size of your development team to increase without reducing productivity of individual developers. All engineers can work independently of the others. Additionally, this build setup ensures that your builds can be reproduced. Using standard SCM workflows can ensure that, at any future time, you can regenerate a specific build allowing for long term maintenance, even if upstream providers are no longer available. Similar to working with distributed SCM tools however, there is additional policy that needs to be in place to enable reproducible, release candidate images. Individual developers have their own copies of the source and can build their own test images but for a proper release engineering effort, development teams will need to establish merging and branching standards and ensure that all changes targeted for release eventually get merged into a well-defined branch. Many upstream projects already have well-defined processes for this kind of release strategy (for instance, using *-stable and *-next branches).

The primary downside of this approach is the lack of familiarity. For example, adding a package to the image normally requires creating a recipe of some kind and then updating the definitions so that the package binaries are included in the image. This is very different from running apt while logged into a running system. The learning curve of these systems can be daunting but the results are more predictable and scalable and are likely a better choice when considering a design for a product that will be mass produced.

Dedicated build systems such as OpenEmbedded and Buildroot use this model as do distro packaging tools such as debootstrap and multistrap. Newer tools such as Isar, debos, and ELBE also use this basic model. Choices abound, and it is worth the investment to learn one or more of these packages for your designs. The long term maintainability and reproducibility of these systems will reduce risk in your design by allowing you to generate reproducible builds, track all the source code, and remove your dependency on third-party providers continued existence.

Conclusion

To be clear, the distributed model does suffer some of the same issues as mentioned for the Golden Master Model; especially the reliance on third parties. This is a consequence of using systems designed by others and cannot be completely avoided unless you choose a completely roll-your-own approach which comes with a significant cost in development and maintenance.

For prototyping and proof-of-concept level design, and a team of just a few developers, the Golden Master Model may well be the right choice given restrictions in time and budget that are present at this stage of development. For low volume, high touch designs, this may be an acceptable trade-off for production use.

For general production use, the benefits in terms of team size scalability, image reproducibility and developer productivity greatly outweigh the learning curve and overhead of systems implementing the distributed model. Support from board and chip vendors is also widely available in these systems reducing the upfront costs of developing with them. For your next product, I strongly recommend starting the design with a serious consideration of the model being used to generate the base OS image. If you choose to prototype with the golden master model with the intention of migrating to the distributed model, make sure to build sufficient time in your schedule for this effort; the estimates will vary widely depending on the specific tooling you choose as well as the scope of the requirements and the out-of-the-box availability of software packages your code relies on.

Comments are closed.