I love a good game, and I particularly enjoy tabletop games because they have many of the same traits that open source has. When you're playing a card game in real life with friends sitting around a table, you can as a group decide that Jokers are wild. Alternately, you could arbitrarily decide that should a Joker come into play, anyone holding an Ace must discard that Ace. Or when a Queen of Diamonds comes into play, everyone must pass their hand to the player on their right. In other words, you can reprogram the rules on a whim because a game is nothing but a mutually agreed-upon set of conditions. To me, what's even better is that you can invent your own games instead of hacking the rules of somebody else's game. From time to time, I do this as a hobbyist, and because I like to combine my hobbies, I tend to design games with only open source and open culture resources.

First of all, it's important to understand that there are, broadly, two facets of a game: flavor and mechanics. The flavor is the story and theme of the game. The mechanics of a game are the rules and the condition of play. The two aren't always completely separate from one another, and there's an elegance to designing a game themed around race cars, for instance, with rules that demand players to perform actions very quickly. However, the flavor and mechanics are just as often treated separately, and it's entirely reasonable to invent a game that could be played with a standard deck of poker cards, but that's themed around space llamas, just for the fun of it.

Open source artwork

If you've ever gone to a museum of modern art, you've probably found yourself standing in front of a canvas painted solid blue and overheard somebody utter this time-honored phrase: "Heck, I could make that!" But the truth is, artwork is hard work. Making art that's pleasing to the eye takes a lot of thought, time, confidence, and skill, so it makes sense that the art is one of the most difficult things to procure for a game you're designing.

I have a few "hacks" on dealing with this classic snag.

1. Find common ground

There's free and open art out there, and a lot of it is very good. The problem is that games usually need more than one art piece. If you're designing a card game, you probably need at least four or six distinct elements (assuming your cards follow the foundations laid out by the Tarot deck) and possibly more. If you spend enough time on it, you can find Creative Commons and Public Domain artwork online on sites like OpenGameArt.org, FreeSVG.org, ArtStation.com, DeviantArt.com, and many others.

If the site you're using doesn't have a Creative Commons search, enter the following words into any search engine, "This work is licensed under a Creative Commons" (the quotes are important, so don't leave those off) and whatever syntax your favorite search engine uses to limit the search to just one site (for example, site:deviantart.com).

Once you have a pool of art to choose from, sort the art that you've found by identifying common themes in the artwork. Two pictures of robots by two different people might look nothing alike, but they're still both robots. Provided you have enough robot-themed art, you can structure the flavor of your game around robots.

2. Commission Creative Commons art

You can hire artists to make custom art for you. I work with artists who use open source paint programs like Krita and Mypaint, and as part of the contract, I specify that the art must be licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Share-alike (CC BY-SA) license. I've only ever had one artist decline the offer because of the license restriction, and most are happy for their artwork to have a potentially larger life than just as part of a hobbyist's self-published game.

3. Make your own

As a trip to the museum of modern art reveals, art is a very flexible term. I've found that as long as I give myself a goal of how many cards or tokens for a game I need to create, I can usually produce something with one of the many graphical creative tools available on Linux. It doesn't have to be anything fancy. Just like modern art, you can paint a card with blue and yellow stripes, another with red and white polka-dots, another with green and purple zig-zags, and nobody but you will ever know that you secretly meant for them to be the lords and ladies of the fairy court, except that you don't know how to draw those. Think about all the simple things you can create in a graphics application, or by tracing photographs of everyday objects, or by remixing classic Poker suits, or Tarot themes, and so on.

Layout

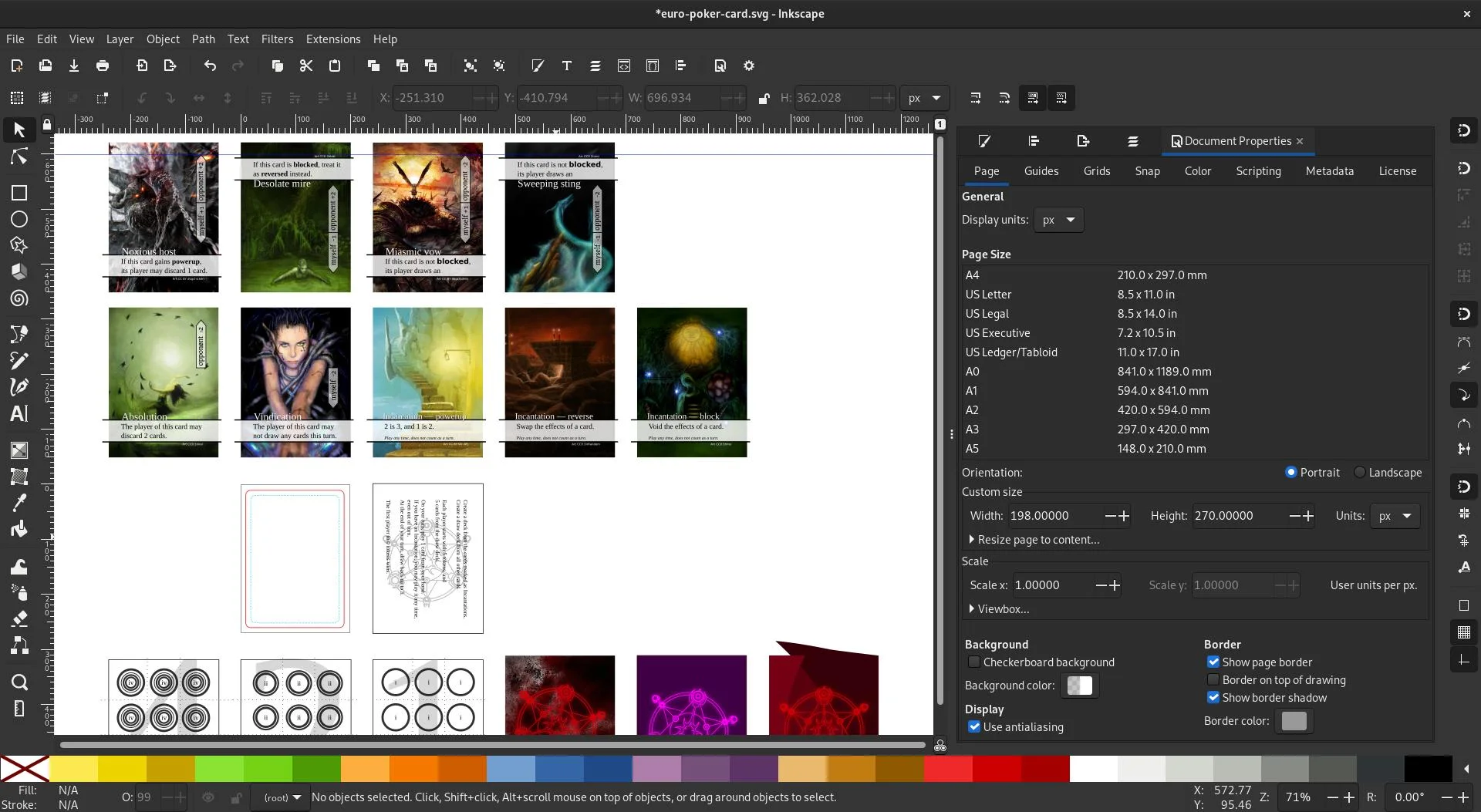

I use Inkscape, Scribus, or GIMP for layout, depending on what my assets are and what manner of design I'm after.

For cards, I find that a simple layout is easy to do and look at, solid colors tend to print better than gradients, and intuitive iconography is best.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

I did the layout in a single Inkscape file for my latest game, which uses just nine images from three or four different artists on OpenGameArt.com. I design the layout of each card in its own file for games with a more extensive set of art and card variety.

Know your target output before you do any layout for your game assets. If you're going to print your game at home, then do the math and figure out how many cards or tokens or tiles you can fit on your default paper size (US Letter for some, A4 for everybody else). If you're printing with a game printer like TheGameCrafter, download the template files.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Mechanics

Game mechanics are the most important part of a game. They're what makes the game a game. Developing rules for a game doesn't have to be a formal process. You can come up with a game on a whim, or take a game that exists and remix its rules until it's something different, fix a game that just doesn't work for you, or mash two different games together. Start simple, using index cards, standard playing cards, or a Tarot deck to mock up how you think your game will work. You can play early game ideas by yourself, but eventually, getting a friend to help is a great way to introduce surprise glitches and optimizations.

Playtest often. Play your game with a diverse set of players, and listen to their feedback. Your game might inspire many players to invent new rules and ideas, so separate feedback about what's broken from feedback about what could be different. You don't have to implement feedback that just iterates your idea, but give careful thoughts to the bug reports.

Once you've decided how you want your rules to work, write them down to make them short and easy to parse. Your rules don't have to convince players to play the game, you don't have to explain the strategy to them, nor do you need to give permission to players to remix the rules. Just tell the players the sequence of steps they need to take in order to make the game work.

Most importantly, consider making your rules open source. Gaming is all about shared experiences, and that ought to include the rules. A Creative Commons or Open Game License ruleset allows other gamers to iterate, remix, and build upon your work. You never know, somebody might come up with a variant that you enjoy more than your own!

Open source gaming

Open source isn't just about software. It's a cultural phenomenon, a natural fit for tabletop games. Take a few evenings to experiment with creating a game. If you're new to it, start with something simple, like this blank card activity:

- Gather up some friends.

- Give each person a few blank index cards, and tell them to write a rule on each card. The rule can be anything ("If you're wearing something red, you win" or "The first person to stand up wins," and so on.)

- On your own index cards, write and, but, or, but not, and not, except, and other conditional phrases.

- Shuffle your deck and deal the cards to all players.

- Each player may play one card per turn.

- The goal is to win, but players may play the and, but, and or cards to modify the conditions of what determines the winner.

It's a fun party game and a nice introduction to thinking like a game designer because it helps you recognize what tends to work as a game mechanic and what doesn't.

And, of course, it's open source.

Comments are closed.