Installing an application on a computer system is pretty simple. You copy files from an archive (like a .zip file) onto the target computer in a place the operating system expects there to be applications. Because many of us are accustomed to having fancy installer "wizards" to help us get software on our computers, the process seems like it should be technically more complex than it is.

What is complex, though, is the issue of what makes up an application. What users think of as a single application actually contains code borrowing from software libraries (i.e., .so files on Linux, .dll files on Windows, and .dylib on macOS) scattered throughout an operating system.

So that users don't have to worry about that veritable matrix of interdependent code, Linux uses a package management system to track what application needs what library, and which library or application has security or feature updates, and what extra data files were installed with each software title. A package manager is, essentially, an installer wizard. They're easy to use, they provide both graphical interfaces and terminal-based interfaces, and they make your life easier. The better you know your distribution's package manager, the easier your life gets.

Installing applications on Linux

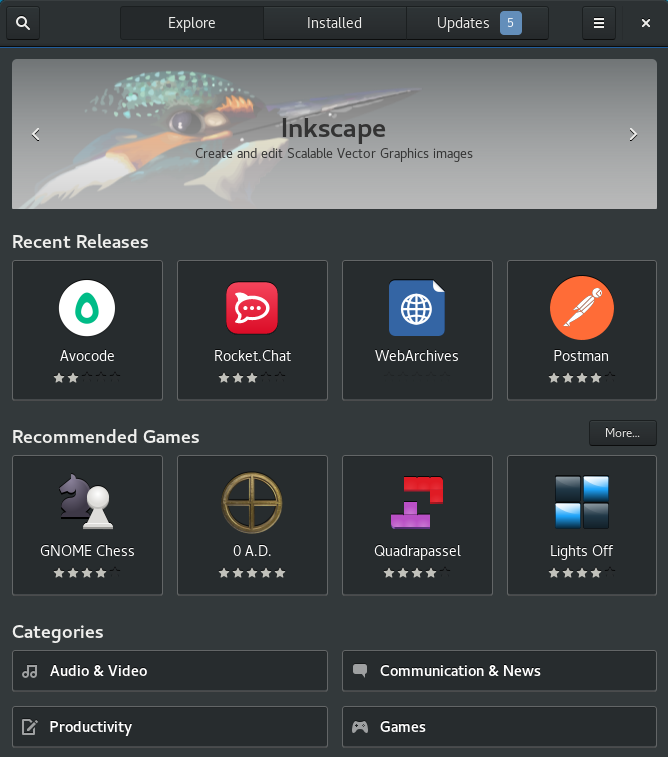

If you're a casual desktop user who wants to install an application on Linux, then you may be looking for GNOME Software, a desktop application browser.

It works as you'd expect: You click through its interface until you find an application that seems like it would be useful, and then you click the Install button.

Alternately, you can open .rpm or .flatpakref packages downloaded from the web in GNOME Software for it to install them for you.

If you're inclined toward controlling your computer with typed commands, read on!

Finding software with dnf

Before you can install an application, you may need to confirm that it exists on your distribution's servers. Usually, searching for the common name of an application with dnf suffices. For instance, say you recently read an article about Cockpit and decide you want to try it. You could search for cockpit to verify that your distribution includes it:

$ dnf search cockpit

Last metadata expiration check: 0:01:46 ago on Tue 18 May 2021 19:18:15 NZST.

==== Name Exactly Matched: cockpit ====

cockpit.x86_64 : Web Console for Linux servers

==== Name & Summary Matched: cockpit ==

cockpit-bridge.x86_64 : Cockpit bridge server-side component

cockpit-composer.noarch : Composer GUI for use with Cockpit

[...]There's an exact match. The package listed as a match is called cockpit.x86_64, but the .x86_64 part of the name only denotes the CPU architecture it's compatible with. By default, your system installs packages with matching CPU architectures, so you can ignore that extension. Therefore, you've confirmed that the package you're looking for is indeed called simply cockpit.

Now you can confidently install it with dnf install. This step requires administrative privileges:

$ sudo dnf install cockpitMore often than not, that's the typical dnf workflow: search and install.

Sometimes, however, the results of dnf search aren't clear to you, or you want more information about a package than just its common name. There are a few relevant dnf subcommands, depending on what information you're after.

Package metadata

If you feel like your search got you close to the package you want, but you're just not sure yet, it's often helpful to take a look at the package's metadata, such as the project's URL and description. To get this info, use the pleasantly intuitive dnf info command:

$ dnf info terminator

Available Packages

Name : terminator

Version : 1.92

Release : 2.el8

Architecture : noarch

Size : 526 k

Source : terminator-1.92-2.el8.src.rpm

Repository : epel

Summary : Store and run multiple GNOME terminals in one window

URL : https://github.com/gnome-terminator

License : GPLv2

Description : Multiple GNOME terminals in one window. This is a project to produce

: an efficient way of filling a large area of screen space with

: terminals. This is done by splitting the window into a resizeable

: grid of terminals. As such, you can produce a very flexible

: arrangements of terminals for different tasks.This info dump tells you the version of the available package, which repository registered with your system provides it, the project's website, and a long description of what it does.

What package provides a file?

Package names don't always match what you're looking for. For instance, suppose you're reading documentation telling you that you must install something called qmake-qt5:

$ dnf search qmake-qt5

No matches found.The dnf database is extensive, so you don't have to restrict yourself to searches for exact matches. You can use the dnf provides command to learn whether anything provides what you're looking for as part of some larger package:

$ dnf provides qmake-qt5

qt5-qtbase-devel-5.12.5-8.el8.i686 : Development files for qt5-qtbase

Repo : appstream

Matched from:

Filename : /usr/bin/qmake-qt5

qt5-qtbase-devel-5.15.2-3.el8.x86_64 : Development files for qt5-qtbase

Repo : appstream

Matched from:

Filename : /usr/bin/qmake-qt5This confirms that the application qmake-qt5 is a part of a package named qt5-qtbase-devel. It also tells you that the application gets installed to /usr/bin, so you know exactly where to find it once it's installed.

What files are included in a package?

There are times when I find myself approaching dnf from a different angle entirely. Sometimes, I've already confirmed that an application is installed on my system; I just can't figure out how I got it. Other times, I know I have a specific package installed, but I'm not clear on exactly what that package put on my system.

If you ever need to "reverse engineer" a package's payload, you can use the dnf repoquery command along with the --list option. This looks at the repository's metadata about a package and returns a list of all files provided by that package:

$ dnf repoquery --list qt5-qtbase-devel

/usr/bin/fixqt4headers.pl

/usr/bin/moc-qt5

/usr/bin/qdbuscpp2xml-qt5

/usr/bin/qdbusxml2cpp-qt5

/usr/bin/qlalr

/usr/bin/qmake-qt5

/usr/bin/qvkgen

/usr/bin/rcc-qt5

[...]These lists can get long, so it helps to pipe the command through less or your favorite pager.

Removing an application

Should you decide you no longer need an application installed on your system, you can use dnf remove to uninstall it, all of the files that were installed as part of its package, and any dependencies that are no longer necessary:

$ dnf remove bigappSometimes, dependencies get installed with one app and are later found useful by some other application you install. In the event that two packages require the same dependency, dnf remove does not remove the dependency. It's not unheard of to end up with a stray package here and there after installing and uninstalling lots of applications. About once a year, I perform a dnf autoremove to clear out any unused packages:

$ dnf autoremoveThis isn't necessary, but it's a housecleaning step that makes me feel better about my computer.

Getting to know dnf

The more you know about how your package manager works, the easier it is for you to install and query applications when necessary. Even if you're not a regular dnf user, it can be useful to know it when you find yourself interfacing with an RPM-based distro.

Having graduated from yum, one of my favorite package managers is the dnf command. While I don't love all its subcommands, I find it to be one of the more robust package management systems out there. Download our dnf cheat sheet to get used to the command, and don't be afraid to try some new tricks with it. Once you get familiar with it, you might find it hard to use anything else.

5 Comments