A few days ago, contributors to Opensource.com were asked to share our personal stories about how we got into programming. Many entertaining and fascinating responses were submitted. It would be interesting to quantify these data in time. Intriguing patterns emerged. The 70s generation was nostalgic about Fortran, punch cards, and dial-up access to shared mainframes. 80s kids (amongst which I qualify) shared stories of C, BASIC, or Pascal and their beloved Atari and Commodore computers. Surprisingly few stories from the 90s arrived. Almost like there's a generation gap. Maybe teenagers were running away in horror from C++, MFC, and the dreaded Hungarian notation, which was the order of the day. Then there's strange silence from the youngest generation. Maybe our young Raspberry Pi enthusiasts are too busy making things.

Here's more about my road to programming.

My first programming language

My first programming language was Microsoft BASIC. I learned it on the mighty MSX SpectraVideo 738 home PC. The MSX standard was a home computer architecture based on the Z80 CPU. Developed in the 80s by Microsoft, it was produced by Sony, Philips, Pioneer, Sharp, Yamaha, and many other vendors. My home country is Poland, and we were still under communist rule, and cut off from modern IT technology due to economic sanctions against us. But the winds of change came during the late 80s, and the MSX Spectravideo made it to my school.

Image CC BY-SA Hans Otten

I was a student at the time, so I wasn't paid. I got so fascinated with programming that I would be willing to pay myself for the pleasure. Thankfully, all schools and universities were free at that time. Imagine you would start your IT career with zero debt! I started during my early high school years, in 1988 in Poland. I had been growing long hair, playing guitar, listening to Black Sabbath, and hoping to have a rock band one day—all the while missing out on computers. And I had a friend, who I'll call Mr. Briefcase. He was another student, and also a computer nerd with a reputation. He entered the room one day and asked how are you? He had to listen to me for a while, because the Polish will tell you how they are, if you ask. Then he said: "Hey, I'm going to the computer lab. You can join me. There's no one there today except me." I jumped excitedly: "The entire evening?" He answered: "Sure thing. I'll be busy, but you can play games and stuff."

When we first entered the lab, it felt like a Star Destroyer command center from Star Wars. The following hardware was available:

- One beautiful IBM PC clone, Spectravideo SVI-838 xPress-16 with an excellent clickety keyboard—no modern mechanical keyboard has yet been able to replicate that experience. Unfortunately, it was off-limits for newcomers like me.

- ZX Spectrums—I was not too fond of these, since they looked like toys with their rubbery keyboards.

- Futuristic MSX SVI-738 computers with color screens and Seikosha dot-matrix printers.

The choice was made. I played for a while but got bored very quickly. I asked Mr. Briefcase:

Me: So what is it that you’re doing?

Briefcase: Programming.

Me: How do you do that?

Briefcase: Here.

And he threw a manual at me.

Hello world

I ran through the "hello world!" examples, and then stumbled onto a chapter about computer graphics. It turned out that our MSX had impressive graphic capabilities. After an hour of struggling with English, which was still foreign to me, there it was—my first working computer program, written in BASIC. I was thrilled, flabbergasted, and completely hooked. I could command this computing device to do things. Beautiful things. Utterly stupid things. Boring things. And it would do them all, without hesitation, line after line, only sometimes responding with Syntax error!

It was pure magic! The very next day, I signed up for the computer lab.

Computer graphics

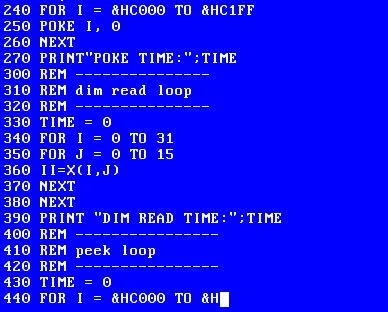

In the following months, I had a lot of fun with computer graphics. Those machines were amazingly efficient in educating young people in computing. Programming a language interpreter was the only way to interact with it. It booted, and you had to enter commands to do anything useful. If you were curious enough, you would inevitably ask—are there more commands? In the end, you got sucked into programming without even knowing it. The entry threshold was so low.

Image CC0 Alan Smithee

For example, to draw a circle on the screen, all I had to do was:

- Boot the computer and wait a few seconds. Yes, it only took seconds to boot!

- Write

10 CIRCLE 100,100,50and press ENTER. Yes, we had to number the lines ourselves. - Write

runand press ENTER.

There was a simplicity to programming in those days. Today, you have choices to make before you write a single line of code. You have to choose your development platform (web, desktop, both), your programming language, your framework, and more.

Of course there are always choices to make, but it feels simpler when all you need are a few resources, and when your computer has only 64kB of memory—the usual on 8-bit machines. To give you a sense of scale—a single high-resolution desktop icon on my Pop_OS Linux box can be bigger than that. Yet within this tiny memory, it could run an operating system and an academic-grade compiler. It could run graphic programs with flawless sprite animation and collision detection. It would play percussion tracks through a programmable noise generator. I have to admit, I know it's possible but I hardly know where to begin with these kinds of activities today.

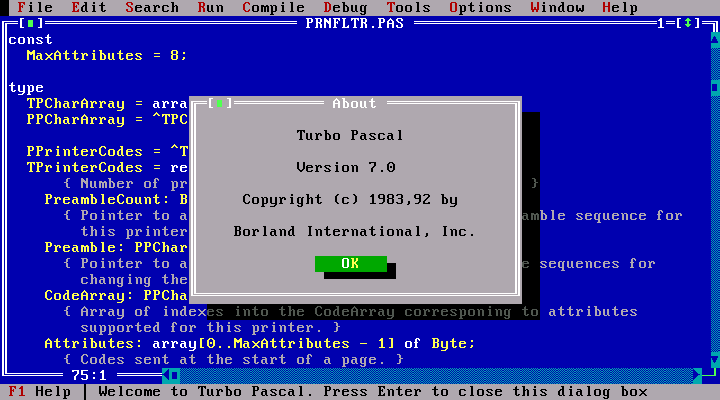

Pascal and beyond

My MSX had a 3.5" floppy drive—an amazing thing these days. One day we received floppies with the CPM 2.2 operating system and a Turbo Pascal 3.0 compiler. This is how I tasted my first actual programming language, while avoiding further exposure to BASIC. Turbo Pascal was beautiful: expressive, concise, safe, and structured. There's an anecdotal theory about why programmers from Central and Eastern Europe have such highly valued skills. In western countries, C and C++ were the order of the day, full of fun quirks and idiosyncrasies. Over here though, we started with Pascal. It was a programming language of choice in schools and universities. The differences between these two are substantial, and the theory is that they wired our young minds in a substantially different way.

Pascal was much more disciplined than C, and it was as "close to the metal" as it gets. Pascal had pointers, direct memory operations, and even asm ... end block for assembly code injection. Yet pointers weren't thrown in everywhere like they are in C, and buffer overflow attacks through null-terminated strings were non-existent. Strings in Pascal is just an array of characters, and only the first entry contains the explicit string length. Simple! It also had a proper module system, precompiled libraries, strict type control, and a blazing fast compiler on top of that.

Turbo Pascal had an enormous impact on the way I think while programming. Eventually it implemented object-oriented programming, and smoothly prepared me for complex software architectures and programming on Windows with Borland Delphi. I touched C and C++ only when I had no other choice.

Decades later, I've realized that all my career, I have unconsciously followed in the footsteps of Anders Hejlsberg. He and his team were creators of a highly successful line of Turbo compilers at Borland. Then they created Delphi, which was a relief for Windows programmers struggling with Visual Basic, WFC, MFC, Charles Petzold books, and Hungarian notation. After Borland, he continued at Microsoft and created .NET, which I happily jumped into. Finally, he created TypeScript, which became the backbone of modern enterprise web development.

Nowadays, I'm busy architecting and developing large web applications for enterprises. JavaScript and TypeScript is the order of the day, with back-ends running on NodeJS, .NET, or Python and writing little utilities and scripts with Python and Bash, and struggling with complexities of cloud computing and YAML. After all these years, I still enjoy the thrill. I can't imagine a more satisfying job that keeps challenging me and never gets dull and boring.

Comments are closed.