Earlier this week some colleagues and I attended a fantastic gathering of business and political leaders called the Emerging Issues Forum. The theme of the forum—interestingly enough for a bunch of business folks—was creativity, and speakers included some of my favorite thinkers/authors who analyze the future of business:

- Roger Martin, Dean of the Rottman School of Management at the University of Toronto, and author of The Responsibility Virus, The Opposable Mind, and a new book on design thinking called The Design of Business.

- Tom Kelley, General Manager of legendary design firm IDEO, and author of The Art of Innovation and The Ten Faces of Innovation. IDEO's CEO Tim Brown also has a book out on the subject on Design Thinking, called Change by Design, which my friend Jonathan Opp wrote a nice review of here.

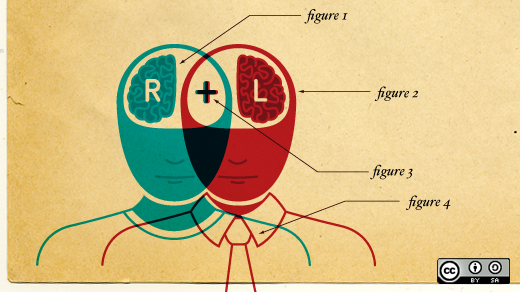

- Daniel Pink, bestselling author of A Whole New Mind, a book that has been extremely influential in my thinking about how the left brain and right brain can play nice in the business world. Pink also has a new book out, called Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us.

During their talks, I couldn’t help but notice all three touched on a similar thematic: the crucial role that inspiring creativity plays in driving innovation.

And all three raised questions about whether our “business-as-usual” (so to speak) business practices are creating the environment that will spur innovation needed to compete in the 21st century (some coverage here, here, and here) or whether they actually stifle creativity and innovation.

Other noted experts, including management guru Gary Hamel and legendary thinker Henry Mintzberg regularly raise similar questions (Mintzberg's essay "How Productivity Killed the American Enterprise", written before the economic collapse, puts him squarely in Nostradamus territory on the subject).

So today I ask you what may seem to be a simple question:

Is the traditional business world at war with creativity? Meaning:

- Why do creative, original ideas face so many challenges seeing the light of day and then surviving in traditional organizations?

- How can our organizations change so that rather than people who are good at “playing the game” always winning, the best ideas can win more often? Meritocracy in action and all that.

- And finally, what could us open source-minded folks teach the traditional business world? How could we help more companies innovate the open source way?

Let's give peace a chance, man. How do we end the war and get the right and left brains in our businesses on a more innovative path?

I’d love to hear what you think.

15 Comments