Municipalities across America should be working to bring open source educational tools to schoolchildren so they will have the necessary digital literacy skills to tap into their creativity and imagination, or even to provide them with valuable future life and workforce skills. And the case of the Feoffees of the Grammar School in Ipswich, Massachusetts—the oldest charitable trust in America—illustrates this point well.

Over 350 years ago, in 1660 William Paine bequeathed 27 acres of land at Little Neck in his will to benefit Ipswich schools and future generations of schoolchildren in the town. In 1647 Massachusetts law required towns to set up grammar schools, whose mission was to prepare young white males for Harvard and the puritan ministry. For hundreds of years, Feoffees, or trustees, acted as beneficiaries for the children and schools of Ipswich. Over the years 167 cottages were built on Little Neck, waterfront property; the Feoffees collected rent money on the cottages.

However, according to parents of students and concerned citizens who are advocating for accountability on the fate of Little Neck in Ipswich, over the last 30 to 50 years or more the Feoffees have not fulfilled their obligations and made little to no contributions to the town's children and schools. Instead, the Feoffees mismanaged the land and kept rents dramatically low, which denied the town and schoolchildren the benefit of revenue (potentially many millions). It is my stance that the focus of the Feoffees (and with other municipalities) should be on developing and making a commitment to renewable open source educational tools for the benefit of future generations of schoolchildren in Ipswich (and elsewhere).

In 17th century New England, paper, books, and other printed materials were expensive and somewhat scarce; literacy through print was uneven. Most books, pamphlets, and broadsheets were imported from England and Europe until printing presses existed in Boston. Yet news and interest in the printed word was widespread. Word of mouth reigned. Many people learned how to read though a hornbook (mainly the alphabet), psalm book, or Bible. Many people had some basic reading skills, but could not write. Others could possibly learn the alphabet enough to write their names, but did not know how to read. Female literacy rates for the 17th century are still difficult to ascertain. Nevertheless, books and printed materials helped to circulate ideas and information, though the scope of it was limited with literacy being uneven and without local printing presses.

In 21st century America, and in many places around the world, paper, books, and other printed materials are no longer expensive, scarce, or restricted; digital technology and digital information is quickly replacing paper, pen, and printed materials.

Digital literacy, however, is still uneven in America and throughout the world. Lack of hardware and software often hampers digital literacy and an importance placed on it. Many schools lack funds to move computers to classrooms. Many schools still confine computer hardware and software to a technology lab or a library. Some high schools do require the use a laptop or tablet today, but lack an integrated digital curriculum or fully understand what digital literacy is.

While the Common Core of State Standards calls for 50% informational text (nonfiction materials from newspaper articles to textbooks) in elementary and high schools across America, there is no similar call or even a consensus or urgency to embrace open source. Children in kindergarten, 1st grade, and 2nd grade learn about the differences between fiction and nonfiction, historical events, or basic scientific ideas or concepts, but do not learn about open source and the differences between them and the more common, commercial-based digital media.

Research and initiatives from the Joan Cooney Ganz Center and The Future of Children show that very young children are facing an unprecedented time of digital communication, technology, and literacy today that elicits our attention. An awareness to what is at stake as society transitions to a digital age for very young children is overdue. Young children today often seamlessly integrate the use of film, radio, television, video games, music, and the telephone with digital technology that previous generations could only fantasize about. Landline phones are becoming a distant thing of the past. And yet six-year-olds need guidance and support wth this unprecedented digital age and to learn digital literacy skills.

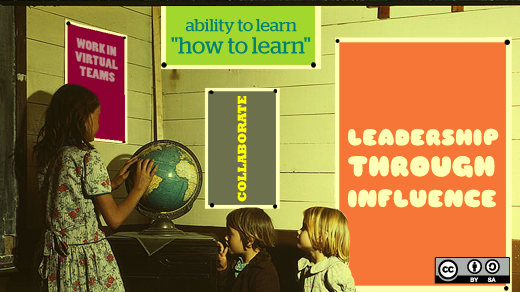

Open source presents a dilemma to these organizations, educators, and parents on when and how to introduce them into young people's lives. At the moment, children aged two to six are being introduced to digital technology, mainly from their parents. But there is a big void in education with open source and showing kids how to create them, use them imaginatively, and gain future life and workforce skills.

Events such as SCALE (Southern California Linux Expo) Kids Conference attempt to bridge this gap, but they need help in doing so. The next generation of open source citizens needs mentors. Some sites do feature digital citizenship and literacy courses for children, but few, if any, include open source.

Common Sense Media has free digital citizenship and classroom literacy courses for children from kindergarten to high school, but nothing on their site, including the digital literacy courses, on open source. Similarly, Digizen has information about digital citizenship and bullying, but nothing on open source. Even the guide, Net Cetera: Chatting with Kids About Being Online, from the federal government, makes no mention of open source and the opportunities for expanding a child's creativity, imagination, and future life and workforce skills.

Open source has the potential to make a surprising, educational impact if we tap the next generation. Parents and educators need to share open source innovations and affect change in their local communities and elsewhere. A forum discussion group where parents, educators, and open source advocates could band together and discuss these issues facing children today would be a place to start.

In fairness, SchoolForge is attempting to do this, though much of the discussion revolves around technical computing issues or particular software or hardware issues, but a broader, wider national (and global) audidence with coalitions of parents and educators to the local level is needed to bring open source in classrooms across America and affect social change.

2 Comments