Jonathan Rauch wrote in the National Journal Saturday on the “radical decentralization” of the tea party. A “Tea Party Patriots coordinator and co-founder” talks about it this way:

“I use the term open-source politics. This is an open source movement.... The movement as a whole is smart.”

No doubt, this has and will continue to be a bandwagon meme equating decentralization automatically with open source and by extension some form of novelty. Rauch, to his credit, focuses more on the decentralization aspect and acknowledges the “yes and no” answer to the novelty question.

We’ve been through this comparison before with the Howard Dean campaign.

Here’s an article from November 2003 based on discussions with Dean’s campaign manager: “The metaphor of choice...is ‘open-source politics’: a two-way campaign in which the supporters openly collaborate...and in which the contributions of the ‘group mind’ prove smarter than that of any lone individual.”

Which leads to some questions. Was the Dean campaign and is the tea party both open source (and does that give us any insight into their thinking), or is one more open than the other? And, what does it actually mean to be doing politics the open source way?

Daniel Kriess, a Ph.D. candidate at Stanford, has been studying the Dean campaign. Although Kriess found that the Dean campaign certainly defined itself as open source, especially in the media, the actual application was limited to a narrow set of tasks.

Open source thinking and practices really only took place in the Internet Division, an area limited to grassroots “fundraising, technical development, and volunteer operations.” Things like policy development, messaging, and strategy weren’t open to supporters in the same way.

Adding to that, this Internet Division was, Kreiss points out, “...embedded within and accountable to a formal organization staffed by political professionals with very different understandings of how political campaigns should be run...”

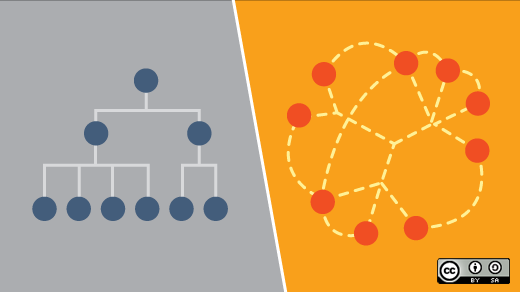

So, was it really open source politics if it was just a division accountable to a traditional command-and-control structure? And, did the campaign run things that way because it culturally didn’t want to be more open, or because it thought it didn’t stand a chance to win if it opened up other campaign functions?

There’s quite a difference between the desired outcome of the Dean campaign (get him elected), and the tea party (self-described as more of a social movement). For them, getting backed officials in office is a welcome side effect along the way.

Even given that, this distinction between facilitating participation or mobilizing people, and developing a tangible policy platform is an important one. In electoral politics, passion and resources are important, but so is the policy direction to know what a group believes, and more importantly, how they might offer alternatives. They feed each other.

Clearly, mobilization can happen the open source way. And here the tea party has an advantage, as the technology and cultural receptivity to use those technologies that lower communication costs is even better today than at the time of the Dean campaign.

Turning to the policy end, where open source software produces code, politics in the end produces law and policy. Even just in GNU/Linux we still talk in terms of tribes, factions, distribution wars, etc. We’ve all seen this mindmap of the evolution of Linux distributions (regardless whether splits were political or functional or some mix of both). But this constant threat and ability to split is often what keeps people involved and innovation going.

From the outside, at first tea party policy appears decentralized, even, chaotic; but, there may be some ingenuity in there. Its members developed a culture with a general values system and welcome all to fill in the rest at their respective level.

Due to the structure of the tea party brand anyone can lay claim to it, whether they’re the only person advocating what they want, or have a broader backing. We’re already seeing this in the various tea party platforms, declarations, etc. out there.

Whereas the Dean campaign proposed the policies and what to believe, the tea party in a sense develop it as they go, and at all levels. Sure, it’s by no means as coherent as a national party, whether Republican or Democrat, but then again, maybe it doesn’t have to be, and maybe it can’t exist any other way.

Here’s where open source starts to be invoked not just in practical methods for mobilization and development of policy, but as a key motivational driver. Kreiss writes: “...open source served the ideological function of allowing many of Dean’s staffers and foot soldiers to imagine themselves as part of a broader movement engaged in a project of techno-democractic reform...”

As the campaign often said, they wanted to “take their country back” a thread shared by the tea party. It was this shared language and commitment to open source principles that kept the passion going.

In the same way, Rauch points out that the tea party may be more appropriately seen as “a social movement, not a political one.” It’s out to “Raise consciousness. Change hearts, not just votes.”

The decentralized organizational structure and operation, although a reflection of its origins, may be the only way a movement advocating the philosophy it holds can operate—the structure is its lifeblood.

By allowing anyone to represent it, it taps volunteers, empowers individuals, and keeps the passion going. When someone says something outlandish to outsiders or even community members, it’s even easier to discount it, as no one is really official.

Rauch closes, “centerless swarms are bad at transactional politics. But they may be pretty good at cultural reform.”

What do you think? Is there anything akin to open source in the way the tea party works, or is it just decentralized? Is it new, or just an extension from grassroots movements seen since the beginning of politics?

Opensource.com

What to read next

2 Comments