As the virtualization of U.S. defense agencies commences, the technology’s many attributes—and drawbacks—are becoming apparent.

Virtualization has enabled users to pack more computing power in a smaller space than ever before. It has also created an abstraction layer between the operating system and hardware, which gives users choice, flexibility, vendor competition and best value for their requirements. But there is a price to be paid in the form of expensive and cumbersome equipment, software licensing and acquisition fees, and long install times and patch cycles.

These challenges have led many administrators to turn to application container technology for answers to their virtualization needs. For this article, we’ll focus specifically on Linux containers, which are made of two core components: the container technology itself and application packaging technology. They enable multiple isolated Linux systems to run on a single control host. Most importantly, they enable the warfighter to have more capabilities in a fraction of the space required by traditional virtualization.

Getting past tradition

In traditional virtualization, each application runs on its own guest operating system. These operating systems need to be individually purchased, installed, and maintained throughout their lifecycles. That can be time-consuming and costly.

With Linux containers, only one Linux operating system needs to be purchased, installed, and maintained. Instead of separating every application by installing them on their own guest operating systems, Linux containers are separated using control groups (cgroups) for resource management; namespaces for process isolation; and NSA-developed Security-Enhanced Linux (SELinux) for security, which enables secure multi-tenancy and reduces the potential for security exploits.

The SELinux-based Linux container isolation provides an additional layer of defense for KVM-based virtualized and cloud environments that use SELinux-based sVirt isolation technology. Similar to a Russian nesting doll, many Linux containers are packed in a VM, many VMs in a hypervisor, and many hypervisors in a secure cloud. The result is a fast, efficient, and lightweight solution that is independent of underlying physical hardware; ideal for the military embedded space.

Finally, by eliminating the overhead of a guest operating system for every application, Linux containers enable increased densities of 10x more applications than traditional virtualization. SWaP (size weight and power) is decreased significantly and the need for traditional virtualization is potentially eliminated, as containers can run natively on bare metal with Linux.

The Docker factor

The need for containerized applications to use the same runtime stack as the underlying system is now unnecessary with the open source Docker project. That’s because Docker enables an application to run the same Linux kernel as the underlying container host but use a wholly different runtime stack:

Docker also:

- Provides the ability to package mission applications and their user space runtime dependencies in a standard format. This enables “golden image” warfighter applications to be shared and deployed on Linux hosts from various vendors who also support Docker.

- Works with Linux container hosts running on physical, virtual or cloud systems. Integrators can develop using agile methods in their cloud and field containerized applications on tactical bare metal appliances without the need of virtualized infrastructure.

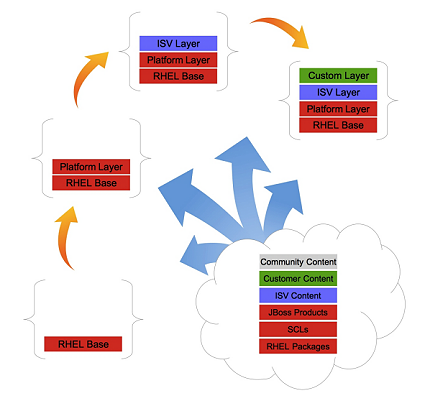

- Lets administrators layer containerized images and put them in an app store-like registry. For instance, the U.S. Army could develop a pre-STIGed Linux container and publish it in an Army app registry for all authorized government and integrator employees’ use. These images could be extended to contain certified layered products and services for Java application servers, Web servers, and more:

Photo from Dave Egts

Integrators could also develop applications based upon these containers and publish them back into the Army registry for use and remixing by the government and other integrators.

The Atomic option

Tactical environments require slimmer containerization footprints that are easier to maintain. Enter Project Atomic.

Project Atomic provides an Atomic host that is actually a slimmed down enterprise Linux distribution whose sole job is to run Docker containers. Its name is derived from two plays upon words: “atomic,” for a small footprint as discussed above, and “atomic operations,” which must be performed entirely or not at all. Atomic hosts are compelling for tactical environments because they enable containerized apps to be uniformly “flashed,” or “reflashed” quickly if a system rebuilding or updating. This is quite different from the traditional approach of patching deployed systems, where configurations can drift from being identical over time, making security measurement extremely difficult.

As the U.S. military continues its march toward virtualization, it will need to operate in an environment that runs on more agile solutions. Linux containers fit that bill nicely, enabling Defense Department agencies to take full advantage of virtualization benefits.

Originally published on DefenseSystems.com as How Linux containers can solve a problem for DOD virtualization. Reposted with permission.

Comments are closed.