Imagine a 20-year-old musician publishing his work today. Let's pretend he's living the fast and reckless life of a rock star and will die young at 45. Because the copyright term has been ratcheted up to life of the author plus 70 years (or 95 years from publication for corporate works), you won't be able to sample his work without permission (for your heartfelt tribute song, of course), until 2105. But since you're not living his rock star lifestyle, maybe you can hang on another 95 years to grab your chance.

"We are the first generation in history to deny our culture to ourselves," Jennifer Jenkins said.

Read part 1 of this series about the upcoming graphic novel. Theft! A History of Music and the history it reviews and, which discusses how copyright entered the picture.

Furthermore, as the new year approaches, we'll soon again "celebrate" Public Domain Day, January 1, which is the day when works entering the public domain in a given year do so. But as I explained for this year's non-celebration, because of copyright changes and extensions, there will be no previously copyrighted works entering the public domain in the US until 2019.

Under the law as it stood until 1978, most music would go into the public domain in 28 years, which would put works from the 80s into the public domain now. But the new terms have been retrospectively applied, sometimes applying to dead musicians, who presumably have other things to worry about besides their copyrights.

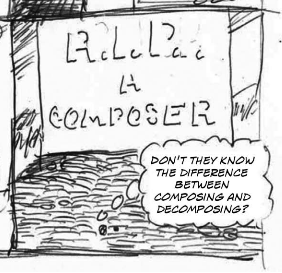

Copyright law has a built-in, careful balance between control and freedom. And we haven't just added a few marbles to one side of the scale—we've dropped an anvil on it. Outside of a conscious choice to release work to the public domain or to use a tool like Creative Commons, nothing you or any of your contemporaries creates will be available for building on, which was not the case for the works of Brahms or Beethoven, or many of the giants of jazz, blues, or rock 'n roll.

The real tragedy is that we're unlike the classical composers and rock 'n roll pioneers in another way. We have the Internet. Remixing software. Sharing tools. The technologies we have now offer anyone unprecedented opportunities for creating and sharing music. We live in a time that has the potential to be the most creative period in history. But the law is constraining that possibility by making those activities illegal.

"The gap between what technology is enabling and what the law is disabling is growing," Jenkins said. This gap will restrict the creativity to the fringes, rather than push it to the mainstream, which in the long term is the culture that is preserved and maintained.

So what do we do about it?

We could roll with increasing regulations. Lose your Internet connection for file sharing. Take away artists' rights to terminate recording contracts. We could go even further. Jail someone for singing in the shower, or for merely thinking about a song. (Those supporting the latter have probably heard me play Karaoke Revolution.)

Or we could turn around and march toward a future of digital revolution and cultural anarchy.

Neither extreme is particularly attractive. To say that we would be better off with a more balanced system is not the same as saying that we should abolish copyright altogether, much less that downloading music is a fundamental human right. But culture should not be degraded for a business model.

What if we could imagine a more balanced debate that includes the interests of artists and creators, record companies, civil liberties, digital freedom, and technological development—not just one of them? By looking to and learning from musical history, we can learn how to treat the fundamental components of how music is made.

Jenkins and her co-author and artist, James Boyle and Keith Aoki, expect to release Theft! A History of Music under a Creative Commons license in the spring or summer of 2011.

Comments are closed.