Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, welcome to another gripping installment of my Six Degrees column. As usual, thanks for the support. So far you folks have helped Slashdot three out of four of these columns, and every one has hit the Top 5 list on Opensource.com, so let's keep this train on rolling.

Please be sure to get your trigger-happy thoughts into the comments box and your wider suggestions into my inbox at jono@jonobacon.org. Your feedback really does help make this column better.

The business of open source

I have long been fascinated by how collaboration works in open source and how we create communities to innovate and build interesting things. While open source continues to expand into diverse and unusual places, we have seen another interesting phenomenon spring up in the wake of the early open source successes: the open organization.

Open source companies are unusual and different. The planning, product development, culture, and business of open source have defined new rules that challenge business traditions, but also open up interesting new opportunities.

While I myself have spent a large chunk of my career working in open organizations, I was keen to get an additional perspective on them, so I sat down with Jim Whitehurst, CEO of Red Hat. Aside from running Red Hat, Jim recently released his first book, The Open Organization: Igniting Passion and Performance, which delves into the DNA of what makes an open organization tick.

An interesting journey

I had never talked to Jim Whitehurst before but was of course familiar with his accomplishments at Red Hat. He joined the company in 2008 as CEO, led them to being the first billion-dollar open source company, and moved Red Hat's stock up three-fold since he started.

I had never talked to Jim Whitehurst before but was of course familiar with his accomplishments at Red Hat. He joined the company in 2008 as CEO, led them to being the first billion-dollar open source company, and moved Red Hat's stock up three-fold since he started.

Whitehurst comes across as genuine and passionate about his work. It is clear that culture and the people that infuse that culture mean a lot to him. He speaks respectfully of his colleagues and dwelled in great detail on the cultural nuances he feels are important in not only making a profitable business, but one that people want to work at.

His descent into openness couldn't be more unusual. Prior to Red Hat he was COO at Delta Airlines, tapped by the CEO at the time to help lead them out of bankruptcy and avoid a hostile takeover by US Airways.

As we delved into this interesting move from airline to entrenched open source company, I posited that this must have been quite a bizarre move for him.

"That is the understatement of the century!" says Whitehurst. He continues, "At Delta I was always called 'that consultant,' and as soon as I came to Red Hat I was called 'that airline guy.'"

It wasn't as unusual as it might have seemed though. Whitehurst's degree from Rice University was in computer science and economics and he was already running Fedora at home. He had experimented with various Linux distributions and his nerdery even extended to putting Rockbox on his iPod.

"I did have some geek cred coming in, but it was clear that in terms of the business, it was chaos, and I had been brought in to clean it up."

In the following months Whitehurst spent time getting to know the new world he was suddenly submerged in. He met with employees and partners. He learned how the unique balance of office workers, remote workers, and community members all fit together. It was strange and unusual, yet compelling.

"Luckily, in the first few months I didn't get to change anything. Soon though I realized, 'Wow, this is an interesting way to run a company and it works really, really well.' I then spent the next nine months learning more about it and this is where I started thinking that I should write a book someday about this—not about what I have done, but what I have learned."

Under the brim

Back in 1993 when Red Hat was formed by Bob Young and Marc Ewing, the notion of an open organization was rare. Like many open companies, Red Hat has learned by doing. Over the years the company created a culture of openness that resonates to this day by utilizing a mishmash of technologies, communication channels, and process.

"We are distributed around the world with many, many of our people being remote" he says. He continues, "We keep people connected with video, we do something called 'the show' each quarter which includes a whole bunch of stories about Red Hat, and groups get together and watch it. We have a whole set of email lists about culture, strategy, and geography. We also talk about the Red Hat multiplier and the behaviors we expect out of people to move forward. The people I highlight in the company are the very people who demonstrate these behaviors."

Red Hat is not unique here. Increasingly companies are providing mixed environments of office and remote workers and putting tools and infrastructure in place to keep those people connected and collaborating.

What makes a company open, though, is the core of how the organization makes decisions, executes, and engages with their staff. I was keen to get to the heart of where Whitehurst sees openness strategically as opposed to tactically.

He sees it in two areas.

"Firstly, open organizations are opt-in. We assume that people are here because they have a choice and that it is participative. Secondly it is that we openly engage people in the decision-making process."

The core of Whitehurst's perspective is in building an environment that facilitates opportunity in which leadership delivers a culture of engagement.

"The mental model of assuming people have a choice and getting them to opt in and get involved flips around your leadership from 'My job is to get people to do X' to 'My job is to build a good environment where people want to work and are enabled to do their best'. It goes from 'Directly I am driving this' to 'Indirectly I am creating the environment where others can do their best.'"

As our conversation progressed, his philosophy got me thinking about the science of behavioral economics that determines how we make decisions based upon psychology, our environment, and other factors.

More specifically, Whitehurst's perspective reminded me of the research by Dr. David Rock that resulted in the SCARF model; an approach to engagement that specifically highlights choice, status, certainty, control over your environment, and other factors, each key to creating fulfilling organizations and work.

When I shared this with him, rather unsurprisingly, the similarities to behavioral economics was not news.

"Economics 101 assumes people are rational, that we assume people have perfect information, that we assume markets have equilibrium. We know none of these things are right. The same can be applied to management," says Whitehurst.

He went on to suggest that "behavioral economics is to economics as what we are talking about here is to management."

Management

Throughout my conversation with Whitehurst it became apparent that much of his perspective, and his determination of what makes a good open organization, is good management. It is clear that he values both the fiduciary and business value that a manager brings as well as the impact they have on people and culture.

He isn't wrong. Management can be the make or break of both financial and cultural success, and this is particularly tricky in an open organization.

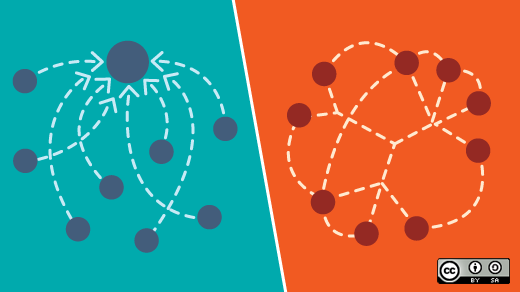

Open companies take a radically different approach to how they assess, develop, deliver, and market their products and services. They have different stake-holders, interests, and technological considerations. They operate in ecosystems where they don't have full control. Open organizations don't live in a walled garden, they exist in a broader commons.

This can be particularly challenging for people who were not born in the brine of open source and open organizations. While these folks can often learn the ropes, the nuances of managing teams so intimately connected to the social, political, and technological subtleties of open source can be near-impossible for some.

"It is hard to bring people in from a proprietary company because the whole mental model is different," says Whitehurst. He continues, "From not selling intellectual property because the IP is free to the way in which we think about product roadmaps to how we influence communities to how you build constructed offerings that provide value beyond just the free bits, all of that stuff is so mind numbing for people from that world."

Whitehurst's view is that the balance of cultural equilibrium and competitive advantage is essentially self-regulating and Red Hat has countered these challenges with extensive onboarding that helps with this self-regulation.

Whitehurst illustrated this further, "We bring people together, bring in senior executives, we have open source luminaries such as Michael Tiemann come in and talk about culture and heritage and why it is important, and the whole week we get great marks on it." He continues, "Ironically, we never really show you how to use your new Linux computer, so some people come out and say 'I have no idea to get anything done, but it was a great week because we focused on culture.'"

This onboarding is essential at this point in Red Hat's continual growth as it heads toward being a $2 billion company with over 7,000 employees. It is impressive to see this level of culture playing such a significant role.

Growth

While any company can start out with the best intentions for an open culture, to foster the right management and leadership, to make their employees feel engaged and for it to feel opt-in, all of that can go out of the window in periods of rapid growth.

Startups often maintain their open culture through the early years of growth, but as the company handbook gets more and more restrictive and as the communication between senior leadership and the junior staff gets wider, problems can set in.

Whitehurst rather unsurprisingly believes that the culture can't be treated secondary to the competitive advantage—that it is the competitive advantage.

"We deeply believe that our source of competitive advantage is a capabilities-based advantage around catalyzing open source communities and then delivering an enterprise product out of it. This capabilities-based advance is so tied to our commercial success that we have to consider them together."

His philosophy is spot-on, and where many have failed, Whitehurst has successfully managed to translate his philosophy into practical action.

The evidence speaks for itself on Glassdoor.com, the website where employees can rate their employers anonymously. Red Hat has netted a 4.1 out of 5 rating with a 95% approval of Whitehurst as CEO—pretty good for a site where it is easy to complain, criticize, and bemoan.

One of the techniques Whitehurst has used to maintain this culture in periods of growth has been to focus heavily on referrals.

"Over half of our hires come from Red Hat referrals," he says. "We spend a lot of time on the Red Hat ambassador program and how to find the right people, but it boils down to the simple saying of 'No one can identify a Redhatter like a Redhatter,' so we do this very purposefully."

Again, the approach seems to be working. Red Hat has grown into a significant open source organization with a large and capable workforce.

In such a period of growth, one of the other beneficial side-effects that has shaken out of an open organization is agility. Unsurprisingly, the culture of the open source collaboration can be used to experiment and explore new technologies and new markets. This helps the organization to be nimble.

"90% of the way in which we work is similar to the open source culture in which we stumble into new areas or find interesting new opportunities, put a few engineers on it, and it grows."

Their portfolio is littered with examples of this approach, with one of the most notable being OpenStack. Red Hat originally put a few engineers on it to explore the technology and they are now significant contributors and have an OpenStack product for their customers.

Conclusion

Like anything in the open source world, everyone has their own view of Red Hat. Love 'em or hate 'em, though, no one can question their tremendous rise to power. From their humble roots in 1993, in 22 years they have grown to be a powerhouse of open source, espousing the values of an open organization and broadly keeping their employees engaged and satisfied through this tectonic change.

Are they perfect? Of course not, but I would argue that the story of how Red Hat has grown and evolved in challenging markets is testament to both their commitment to an open culture as well as the leadership of Whitehurst and the wider senior management team. It is hard enough leading a startup through that kind of change, let alone a company the size of Red Hat.

Exploding the picture out a little wider from Red Hat specifically, the opportunity of an open organization is tremendous. As Whitehurst shared, while it may be unconventional in a traditional business sense, being an open company can net a tremendous culture, agility in exploring new markets, planning and delivering products, relations with other communities, increased market opportunity, and the financial gains that are associated with this amalgam of benefits.

Cynics may argue that Whitehurst will tell me anything to shill his book, but I have spent the majority of my career working for similar organizations and working with execs in those organizations and my bullshit radar had barely a flicker on it. This story is not unique to Red Hat—Red Hat is merely a tremendous illustration of what an open organization can look like.

As ever, I want to hear your feedback. What do you think about Whitehurst's perspective? What are the opportunities for an open organization? What other examples of open organizations would you recommend? What are the challenges that face open organizations moving forward? Let me know in the comments, and I will look forward to seeing you all next month!

Follow the conversation on Twitter #theopenorg

Degrees

This article is part of Jono Bacon's Six Degrees column, where he shares his thoughts and perspectives on culture, communities, and trends in open source.

5 Comments