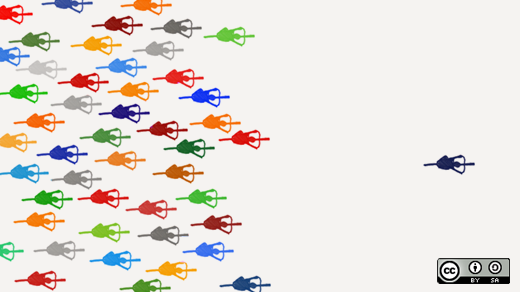

If you've ever watched a road bike race like the Tour de France, you know the peloton is the big group of riders that cluster together during the race to reduce drag. It's a great example of collaboration in action. But let's face it: the people in the middle of the peloton may go faster than they would otherwise, but they don't win the race.

When it comes to creating and innovating, most companies (and employees) are in the peloton. They are doing enough to survive, but they are stuck in the pack. And if they stay in the pack too long, they lose.

Escaping the peloton is tough. Often, you see a cyclist break away, sprint for a while, only to get sucked back into the main group over time as the pressures of making a go independently prove too much.

You've probably felt this way at work. You come up with an amazing idea, one that will change the company forever. But little by little, people—even the well-meaning ones—chip away at its soul, until the idea goes from being amazing to, well, average. You end up being sucked back into the peloton.

After this happens one too many times, you may feel like you want to stop collaborating and try to make things happen on your own. Don't do it. Even Lance Armstrong could rarely break away from the peloton without his teammates' help.

Instead, here are three tips to help you escape the creativity peloton without giving up on collaboration.

1. Tip #1: Rotate leadership regularly.

In a bike race, a successful breakaway often has two or more riders who escape together. They avoid getting sucked back by rotating who is in front, so everyone gets an opportunity to lead and to rest.

In the open source world, the Fedora Project is a great example of rotating leadership. I happen to know all five people who have been Fedora Project Leader over the years. When taking over the reigns, each brought unique perspective and new energy to the project.

I've discussed leadership strategy over the years with Greg DeKoenigberg and Max Spevack, two former project leaders, and they've told me that regular rotation of project leadership is a very deliberate strategy.

My view? Rotating leadership is a brilliant way to sustain a breakaway. Continually investing. In engaging new leaders, recruiting new talent, bringing in fresh ideas, and (at least in Fedora's case) keeping the old leaders deeply engaged too.

2. Tip #2: Collaborate only with those who share the vision.

Collaboration works. But only when everyone is trying to achieve the same goal. The Fedora Project is a good example here as well. People join because they believe in the core mission of the project. Those who don't believe the mission? They can go elsewhere.

Look around. Do the people in your breakaway group all share a common vision? Has it been articulated clearly? In my experience, when collaboration doesn't work it is often for one of two reasons: 1) lack of a common understanding of the mission (not on purpose) or 2) an outbreak of "clobberation" (totally on purpose).

I've written previously about the concept of "clobberation," the art of beating someone into submission under the guise of collaboration. If someone in your group is clobberating, they are trying to impose their ideas on others without being open to new ideas themselves. All mouth, no ears.

Nothing kills a shared vision faster than an individual who puts their personal vision ahead of the goals of the group. So articulate the vision clearly, come back to it regularly, ensure that new members deeply understand what it means, and weed out clobberators along the way.

3. Tip #3: Always build.

There is no rule that says you have to collaborate with everyone. At the same time you weed out clobberators, also weed out devil's advocates, in the sense that Tom Kelley of IDEO refers to them:

"Rather than support and grow the ideas of their team members, the Devil’s Advocate assumes the most negative possible perspective to quash fledgling concepts, often doing so with those oft-heard words, “Let me just play Devil’s Advocate for a minute…” This person represents a subtle yet toxic danger to your organization’s cause, greatly diminishing the chance for innovation with their negativity and naysaying."

A successful breakaway relies on strength, power, and endurance, but it also relies on fragile things like hope and faith. Nothing destroys hope, faith, and belief in a common vision faster than people who chip away at it. So don't tolerate a devil's advocate who tears down the shared vision of your team. Especially when it is you.

Trying to keep yourself in an "always building" mindset. Meaning, always building on the ideas of others, never destroying them. Rather than criticize an idea you don't like, replace it with a better one. Police your group so that others are doing the same. In my view, this is the way a healthy meritocracy works and a way to ensure the best ideas have a chance to win.

So there. Three simple ideas that may help your team avoid getting sucked back into the peloton. But why stop at three? Do you have any tips or experiences to share? Feel free to add them below.

5 Comments