The seventh season of Fox’s So You Think You Can Dance crowned its latest champion last week, and for the first time since the show debuted in 2005, I did not care. The first six seasons were a fantastically guilty pleasure—like a hip flask of whiskey at a dry wedding—that I hid from friends and colleagues. This year’s contest, however, proved beautifully boring. The choreography and dancing were still stellar but something was missing all season that I could not enunciate.

Then a friend shared a video with me of four young men in Oakland dancing on a street corner. I was spellbound. After watching the video for the fiftieth time, I realized that the video’s powerful draw rested in the sense of playfulness and improvisation that pervades the entire clip. (I particularly loved the masked man’s speed skater pose in the middle of Oakland traffic.) It eventually dawned on me that the spontaneity of the video was the missing element in this year's So You Think You Can Dance.

For those unfamiliar with the show, the format changed this year so that only ten dancers actually made the show (as oppose to twenty in past seasons). While the new format made for supposedly "better" dancing, it cut out the handful of street-trained dancers (B-boys and girls, tappers, folk dancers) who usually made the show so interesting. The show’s dullness (to paraphrase an Irving Berlin number from White Christmas) is because instead of dance, they were doing choreography.

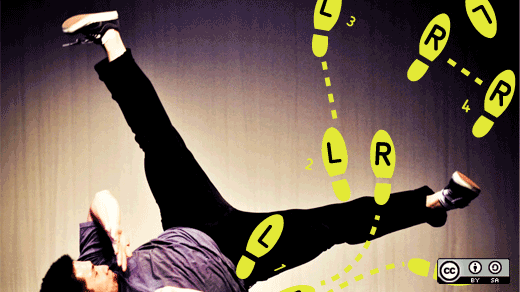

Vernacular dancing—as opposed to choreographed dancing—is most often learned through observation and perfected by participation rather than formal dance training. The genius of vernacular dancing—such as b-boying (the preferred term for "breakdancing")—is the ability of the artist to improvise and incorporate other styles and sources into their routines. For the modern b-boy, there is inspiration everywhere. Watch Scott Willis perform a routine that is as much martial artistry and gymnastics as dance or David Elsewhere’s infamous 2001 performance that borrows from sources as diverse as science fiction and contortionism. This tradition of incorporation and improvisation not only ensures that these dances stay relevant but—more importantly—creates a dance style that is open to virtually everyone.

Street dancing also shares an obvious parallel with the principles of open source. B-boys develop their moves through collaboration and barter. This effort most often occurs in the open public, and the final product is usually available for free (or a donation to the "crew"). Choreography, on the other hand, is a partnership between a writer (literally a "dance writer") and highly-trained artists. The partnership can be stunning, moving, and even political. But unlike street dancing, choreography takes place outside the public gaze and descends—deus ex machina—onto the stage to a very entertained audience. There is no doubt that choreographed dance is beautiful.

But, as this season of SYTYCD showed, I prefer the open and collaborative style of vernacular dance. While I appreciate beautiful choreography, vernacular dance has the unique ability to make people want to get involved, to move and to dance themselves. It is not put on the pedestal of the stage because it doesn’t belong there. Instead, it belongs in the street where it is owned by anyone willing to join in, to improvise or to simply dance.

So give me the heps doin’ steps, the Jakes doin’ breaks, and the chicks doin’ kicks. I will always prefer dance to choreography.

1 Comment