I’ve had many conversations recently that have me looking at a crucial question that impacts neurodivergent corporate employees and their managers: how do we understand, encourage, measure, nurture, and assess the career development of neurodivergent people? Development opportunities, and how managers assess performance, are critical aspects of career growth, financial compensation, morale, feelings of self worth, happiness, employee retention, and the ability of individuals and companies to achieve their goals. And yet, I believe it is something that can be subjective, underappreciated, and under-invested in. As a late-diagnosed autistic person who has had significant anxiety, social phobia, and other mental health conditions for my entire career, and as someone who has been in senior leadership roles, leading hundreds of employees, I’ve thought about this quite a bit.

When I talk about assessing performance I don’t just mean formal performance reviews that happen periodically (annually, semi-annually, quarterly). I’m also referring to career development and advancement, which is inevitably linked to performance appraisals. There are two scenarios that I’ve been hearing about as I speak to both managers and neurodivergent individual contributors, and each one has two different perspectives:

-

The manager feels the employee is presenting some kind of performance problem, or the employee feels the manager does not understand them or fairly assess their work.

-

The employee feels they are not being given opportunities for advancement, or the manager feels the employee does not consistently demonstrate the behaviors expected of more senior levels.

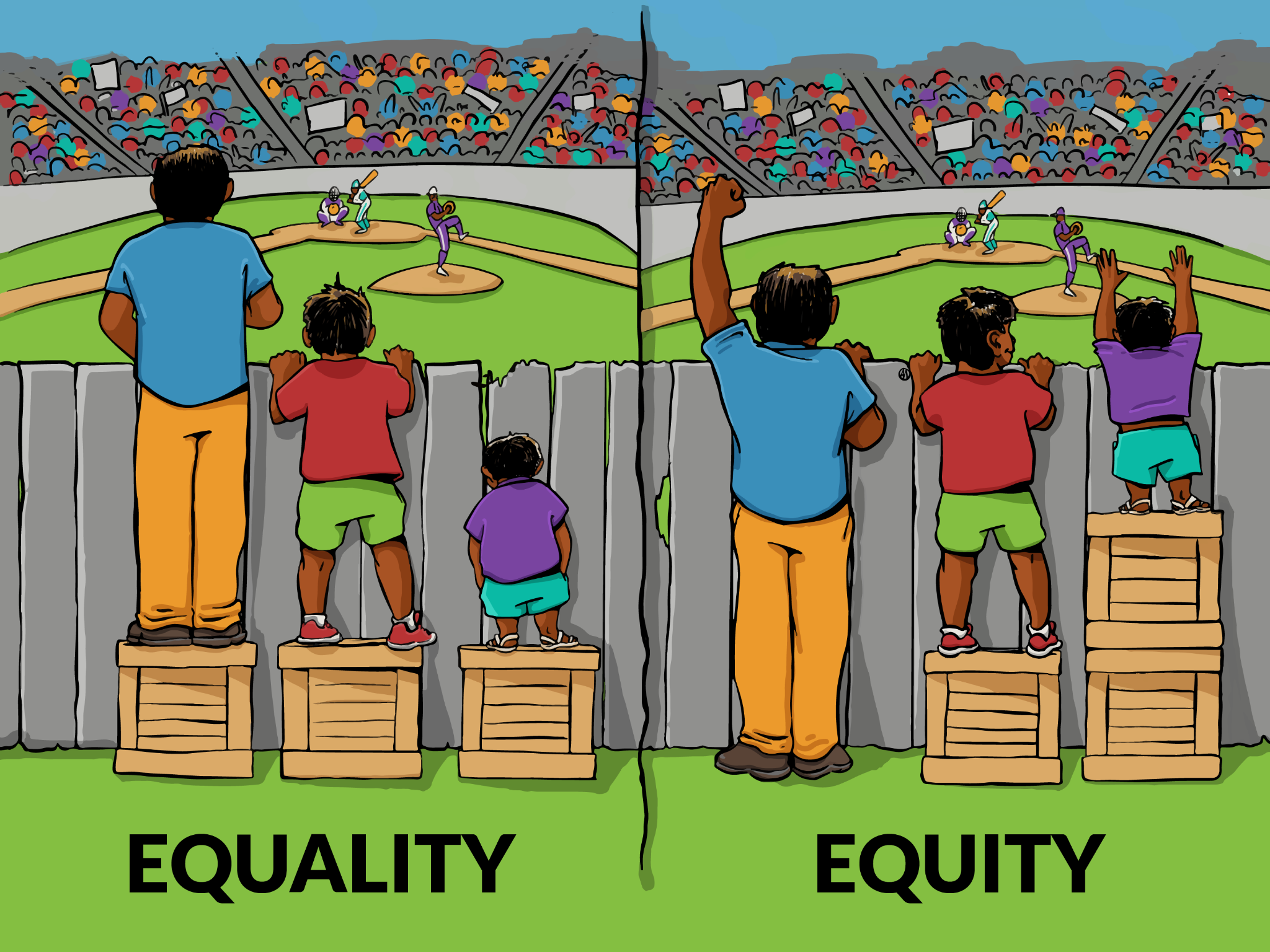

These different perspectives are at the root of the problem. Neurodivergent people experience the world in fundamentally different ways, and many work hard to live up to the expectations set by the social norms of their environment. This process (often called "masking") is hard work that is emotionally exhausting and can also be degrading. The neurotypical manager, on the other hand, may have no idea that the employee experiences the world differently; they may want to judge all employees by the same standards out of a sense of fairness, without realizing that those standards affect various employees differently. That sensibility reminds me of this meme that has been a popular way to illustrate these different perspectives:

(image CC BY-SA 4.0 Interaction Institute for Social Change | Artist: Angus Maguire)

It’s easy to see in the illustration that if each person of a different height is given the same size box to stand on, one of them does not get the benefit of the accommodation that the others enjoy. But, what if you were the person who handed out these boxes, and you never saw what they were being used for?

If the shortest person came back to you and asked for a second box, you might say, “I only have one box for each person - if I give two to you, then everyone would want two, and I don’t have enough.” The person might not want to explain that they need two because they are shorter than everyone else. That could be embarrassing for them, or demeaning. Why should they have to spell out how they are considered “less than” compared to their taller peers, to convince you that they are deserving of a second box?

If you are a neurotypical manager, you may have no idea that some of your employees are unable to see over the fence and some are, because you don’t even know that the fence is there. Imagine if these people were not just watching the game, but if their job was to report on it. If the person who couldn’t see over the fence was your employee, you’d probably want him to be able to focus on the game instead of worrying about finding a box to stand on. Ideally, you’d be proactively working to make sure all of your employees had the tools they need to do their jobs without having to spend time and energy on unrelated tasks.

To illustrate the disconnect, here are some comments and questions I’ve gotten from neurotypical people managers and neurodivergent individual contributors:

Neurotypical people managers (who may or may not know that the employee is neurodivergent):

-

My employee asks for things that nobody else asks for and that seem like “nice to haves”.

-

The performance of this employee is inconsistent. I try to be accommodating, but I have no idea what to expect from week to week.

-

Where is the line between providing accommodations to an employee and implementing a performance improvement plan?

-

I know this employee wants to get promoted, but they aren’t demonstrating senior-level behaviors; they need things from me that other senior-level people don’t need.

Neurodivergent individual contributors:

-

My manager starts with judgment instead of curiosity. Why does my manager approach me with “this is a performance issue” rather than asking me how I’m doing and what they can do to support me?

-

I get great feedback from my manager for months and then suddenly they start talking to me like I’m causing some kind of disruption on the team, or like I’m a problem employee.

-

Why do managers have such a hard time understanding that what was easy for them might not be easy for everyone? Why do they forget that they also had things in their career journey that they struggled with?

-

When I ask for simple accommodations that would be easy and free to implement, my manager reacts as if it’s a huge burden or major inconvenience.

As I talk to both neurodivergent employees and neurotypical people managers, I can see that they are both describing the same situations but from very different perspectives. Where the employee sees inconsistent feedback, the manager sees inconsistent performance. Where the employee sees a request for a simple accommodation scoffed at, the manager sees an associate asking for something that they feel shouldn’t be necessary. Where the manager sees a need to address a performance issue, the employee is wondering why their manager can’t be more supportive and empathetic.

As with many interpersonal dynamics at work, open communication and transparent behavioral norms are critical factors in helping to bridge the gap. But, this topic can be challenging (and traumatic) for neurodivergent employees, and it can be awkward and confusing for neurotypical managers. As a result, the conversations that would help resolve the conflict may not happen. Here are some ideas to help structure and motivate communication that I hope will promote more mutual understanding.

Fostering open communication

I believe that open communication is a critical part of employee development and plays a big role in the impact employees can have with their work. When we discuss open communication between managers and their employees, it’s important to keep power dynamics in mind.

Managers, whether they realize it or not, have a lot of power over their employees. They determine pay, rewards, career progression, development opportunities, and can help employees understand their value within the team and organization. Many managers consider themselves "open" and "accessible," but it may not feel that way to a lot of employees—especially neurodivergent ones.

No matter how friendly a manager is, no matter how many times they may say, “My door is always open," some employees will still be nervous or hesitant about approaching people in positions of power. Due to the existence of this power structure (even in relatively “open” or “flat” organizations), I encourage managers to think about how they can lessen the burden of communication for employees. Managers have the structural advantage; they should take the initiative to establish communication channels.

Many neurodivergent people, for example, have experienced trauma in their lives, and received a lot of negative attention that focuses on their behavior, often from direct supervisors at work, teachers or administrators at school, or even parents at home. A neurodivergent employee who has experienced a history of criticism or negative consequences in response to their behavior, the disclosure of their condition, or an articulation of their needs in the past, may find it difficult to approach their manager to ask for help or accommodations. Knowing that employees may not come to them, managers can be proactive in scheduling regular time with each team member, and also be more deliberate about asking questions based on their observations.

With the goal of strengthening the impact of each employee, below are some examples in a scenario where the manager may have concerns about the work the employee is doing:

-

I wanted to ask if everything is OK and if there is any way I can better support you at this time? (Open the conversation with empathy and curiosity).

-

I thought it might be good if I clarified my expectations on this project, so that you have a better idea of what I’d like to see at each milestone, would that be helpful? (Offering to clarify expectations can reduce anxiety for neurodivergent people and relieve the pressure from them to ask).

-

I think you have been doing a great job on [share some examples]. How do you feel things have been going? (Acknowledge the positive and get the employee’s perspective before you point out areas of concern).

-

I realize this is a stressful project and we’ve got some milestones looming - I wanted to check in on how your stress levels are and whether that’s something you might need help with? (Start by offering help and showing empathy if you have concerns, which can make it safer for the associate to acknowledge their needs).

Making social norms transparent

Whether they talk about it or not, teams establish and operate according to social norms. If those norms are not openly discussed, there might be some unspoken expectations that negatively impact some employees or that some people don’t understand. One of the most effective tools I’ve used for fostering team dynamics is to clearly establish expectations for team interactions through the use of a social contract.

A social contract is developed collaboratively with the entire team and seeks to define norms of behavior and shared expectations for how the team works together—openly and transparently. Establishing these guidelines openly is helpful for all team members. For neurodivergent folks, it is especially useful as it takes away a source of stress that can use energy better applied to important work—the stress of having to figure out expectations of colleagues and managers.

The Open Practice Library contains a detailed description of one process for creating a social contract. Below are some examples of potential social contract agreements, with explanations in parentheses after each one. Note that each team creates its own social contract together, so they are all unique and they may need to be revisited as the team changes. These are just a few ideas that could help start the process.

-

Include an agenda in all meeting invitations (nobody does this! But it’s so simple and helpful, not just to set expectations but to ensure a productive use of time).

-

For meetings with more than two or three people, raise your hand to speak using the raise hand functionality on video calls. (Raising your hand accomplishes several things: it gives people a way to satisfy the urge to speak without interrupting their colleagues, it creates a queue to give everyone a chance to speak who wants to, and it provides a way for more introverted team members to indicate they have something to say without forcing them to interject over more talkative colleagues.)

-

Don’t assume intent (positive or negative), but default to curiosity and try to understand diverging viewpoints. (Assuming positive intent can be an excuse for bad behavior, assuming negative intent can create conflict.)

-

Don’t question the experiences of others; accept the reality of a situation that is presented to you. (This helps promote mutual understanding and curiosity instead of fostering an environment of skepticism and judgment.)

-

Make sure every meeting has an appointed note taker and a facilitator to keep the meeting focused. The note takers should send the notes to the attendees afterward with clearly defined action items noting who is responsible for each one. These roles should be rotated for equal distribution over time. (Neurodivergent employees may have an especially hard time with executive function, which can include follow up on action items from discussions if they aren’t well noted.)

-

Share your needs and preferences. For example, “I can focus better on our discussion if I turn off my video and pace around while we talk.” Or, “When I’m listening carefully, my eyes wander and I might look distracted even though I’m not.” (If everyone shares their needs up front, then nobody has to assume anything when someone turns off their camera or looks distracted.)

Conclusion

Be mindful that there are many conditions that could make someone neurodivergent, and many of those conditions themselves present with a wide spectrum of characteristics. There is no single approach, no one answer, no "rule of thumb" for how to work with neurodivergent colleagues. That’s why I focus on the more general concepts of communication and transparent team norms rather than specific tactics. The ideas I’ve shared here can, I believe, be part of growing as a leader, being able to manage and work within larger and more complex organizations, and effectively working with diverse groups of employees at all levels.

Learning how to better support neurodivergent team members is not something that is only beneficial to those individuals; all of these suggestions are helpful to all people, and also help create a more productive and safer team environment.

Comments are closed.