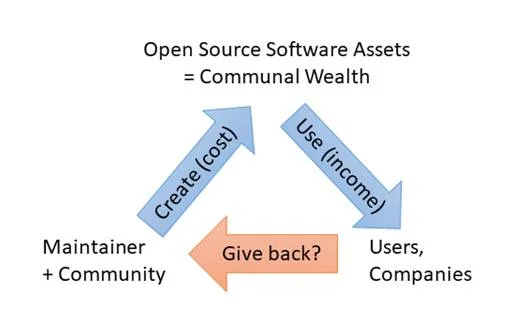

If wealth is the abundance of valuable possessions, open source has a wealth of software. While no one “owns” open source, some are better than others at converting this communal wealth to personal wealth.

Many open source project maintainers who produce free open source software do not have a model for deriving income from the assets they have created. However, companies that use open source software to enhance their products and services convert this valuable asset into income.

The open source ecosystem needs novel mechanisms to distribute privatized wealth back to maintainers if open source projects are to remain sustainable. In this post, I'll discuss the challenges of distributing wealth more fairly, starting with three key observations:

- We need to identify projects that are important and need funding.

- We lack fair rules for distributing money among open source project contributors.

- Transaction costs are too high in underbanked areas. Bugmark and ossgrants (both discussed below) are two project ideas for addressing this problem.

Wealth creation in open source

The wealth created by open source rests today on an imbalance between those who bear the costs and those who enjoy the income. Consider the following example:

An amateur developer creates an open source project as a side project or hobby and releases the software free of charge. The software increases communal wealth when users derive value from it. Companies in particular leverage the open source software in their innovation stream, building products and services with less investment and converting valuable open source software assets into income.

A growing user base brings more support inquiries, bug reports, and feature requests, which take more time and increase costs for the maintainer. A community of contributors might form and share the work of developing and maintaining the software. Sharing the cost of creating communal wealth by contributing, however, does not provide income for the maintainer, who cannot generate personal wealth without mechanisms that distribute income from other users.

It is important to recognize that maintainers need to make a living, and if they have no income from open source projects, they likely have another job—which reduces the time they can spend on maintaining open source software. A lack of funding for open source projects becomes problematic when the software is part of our modern infrastructure and requires long-term maintenance.

The question then becomes: How can the wealth created by use of open source software be distributed to support long-term maintenance by paying maintainers?

At MozFest 2018, 23 people gathered to discuss this question. In small groups, participants discussed problems of interest, chose one problem to work on, and later presented their solutions to the larger group. This post summarizes key takeaways from this presentation and draws on ideas discussed during Sustain Summit 2018.

Participants in the MozFest 2018 met to discuss open source wealth distribution.

Why and how to share wealth

A central question is this: Why would companies share the income they generate from using open source software?

For-profit companies are seen as profit maximizers, and sharing revenue with open source maintainers, who license their intellectual property for free, seems counterintuitive. One survey found that 50% of respondents believe that large tech companies gain more from using open source than they contribute, which demonstrates that companies generate means to give back by using open source. (Note that I am not referring to the many open source projects companies actively maintain, or those that a company started. The focus here is on volunteer-driven communities.)

Three concrete value propositions can convince a company to pay open source maintainers:

- Donating to open source projects earns a good name within the open source ecosystem. Donating to a project or a maintainer—for example via Patreon, OpenCollective, or an open source foundation—funds development work without exerting influence.

- Funding open source maintenance ensures that an open source project will be updated and vulnerabilities fixed, which is important for companies that rely on the software for their products, services, and infrastructure.

- A company gains influence over the strategic direction of an open source project when a donation or membership fee is rewarded with access to core maintainers. Special access can require that maintainers sign non-disclosure agreements and help develop solutions for vulnerabilities that may not yet have been publicly disclosed.

An open source project can also start a company that provides hosting and support services, and collect funds by selling their services. This is the most formalized way of securing funds and provides a clear value proposition. The key point is that a maintainer must figure out how to participate in the economy around open source software.

Distributing wealth: 3 practical issues

The following issues arise when the donation model is used:

First, not every project benefits equally from funds. Do you rely on open source software that might become unsupported if you do not donate to the project? The goal of such an evaluation is to find weak spots in an open source supply chain that can be strengthened with the least amount of cost. Consider using metrics, like the ones created by the CHAOSS project, for determining the health of an open source project. How exactly to identify open source projects that need funding before they become unmaintained is an unsolved problem. The Core Infrastructure Initiative has developed the Census Project to work on a solution. TideLift takes an innovative approach, paying more than $1 million to open source project maintainers based on how much a project is used.

Second, how should funds be distributed among open source project members? Defining how donations will be used should be declared upfront to avoid conflict. One approach might be to recognize individual contributors based on their contributions. For example, you could distribute funds based on the number of issues closed, commits accepted, lines added, wiki pages edited, documentation pages revised, forum messages posted, blog posts published, or other quantifiable contributions. But not all contribution types to a project can be measured—for example, organizing meetings and presenting at conferences are valuable but time-intensive contributions that do not produce trace data in a collaboration software. Every project must set its own rules, but we can share stories and best practices. Open Collective brings this conversation to the public.

Third, transaction costs hinder fair distribution of the wealth created by open source. Specifically, many people in underbanked regions struggle with the logistics of receiving payments. When an open source team member must wait for hours to cash a check, the cost of the time might outweigh the amount they receive for their work. This very real problem may be beyond the scope of what open source projects can do (except perhaps initiatives for Web3), but it deserves attention. Ultimately, the solution is to bring banking to all people and improve the interoperability of banking systems around the world.

Facilitating and incentivizing wealth transfer

There are many initiatives to solve the sustainability problem in open source, but I'll highlight two projects that I find intriguing.

Bugmark answers the question of who within an open source project should get paid, and how much, by creating a marketplace that introduces price signals to open source. The Bugmark exchange allows trading on the status of an issue—for example, issues listed by an open source project on their GitHub issue tracker. Unlike bug bounties, trading on the status of an issue is independent of doing work. By decoupling payment and work, Bugmark has the potential to fund open source work that is not reliant on fixing an issue. For example, a project member who does bug triaging, an honorable but tedious task, has in-depth knowledge of how a project is doing and what is being worked on. This person can use their insider knowledge to trade on Bugmark and earn money. For more details on how Bugmark works, I recommend this publication.

Funding Index is an early-stage idea that revolves around donations. Donations provide a project with money without restrictions. Donations benefit companies, but the publicity effect is short-lived. At SustainSummit, we developed an idea to capture donations more permanently and create a funding index. Donations would be logged and aggregated across companies and projects. Similar to consumer rating agencies that rate products and services, this index would rate companies by how much they donate to open source projects relative to how many employees they have. We could produce badges for “#1 donor to open source,” “#1 donor to infrastructure open source projects,” or “#1 mid-sized company donor to open source.” Such a badge would extend the publicity effect of donations and hopefully incentivize companies to donate more. Funding Index exists in a first prototype and welcomes discussions on the Discourse Forum.

Sustainability is more than funding

Funding helps to pay for living expenses, servers, stickers, and travel to conferences to enable face-to-face collaboration. Funding is a necessary component of a sustainable open source project, but it requires additional elements.

A sustainable open source project fosters a healthy community, which is welcoming, provides a productive work environment, supports its members, and is prepared to let members move on when their focus in life changes. These governance and community concerns build the foundation from which open source projects work, and once they are in place, funding can leverage the work and help project members excel.

A final thought: Companies that are willing to financially support open source projects need to see the business value. Currently, there is no single solution that fits all open source project contexts. Every open source project may need to experiment for themselves and find a way to secure funds. Umbraco, for example, built a sustainable business around its open source CMS system and has experimented with 11 different business models since its inception in 2004.

More conversations are needed, and experiences must be shared. SustainOSS.org brings sustainers together to have these conversations. In conclusion, fair distribution of the wealth created by open source can enhance what already works well in open source, but it will not replace traditional open source practices.

Post Scriptum

I acknowledge that companies and foundations also create open source projects. Sustainability issues exist nonetheless, and takeaways transfer.

Acknowledgments

I'd like to thank all MozFest 2018 session participants, especially the note-takers. I appreciate constructive feedback from Sean Goggins and Tobie Langel. I received a Linux Foundation Community Travel Fund to present at Open Source Summit Europe 2018 in Edinburgh, which allowed me to participate in the SustainSummit and MozFest in London later during the same week. This work is supported through the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Digital Technology grant on Open Source Health and Sustainability, Num: 8434

2 Comments