The oldest joke in open source software is the statement that "the code is self-documenting." Experience shows that reading the source is akin to listening to the weather forecast: sensible people still go outside and check the sky. What follows are some tips on how to inspect and observe Linux systems at boot by leveraging knowledge of familiar debugging tools. Analyzing the boot processes of systems that are functioning well prepares users and developers to deal with the inevitable failures.

In some ways, the boot process is surprisingly simple. The kernel starts up single-threaded and synchronous on a single core and seems almost comprehensible to the pitiful human mind. But how does the kernel itself get started? What functions do initrd (initial ramdisk) and bootloaders perform? And wait, why is the LED on the Ethernet port always on?

Read on for answers to these and other questions; the code for the described demos and exercises is also available on GitHub.

The beginning of boot: the OFF state

Wake-on-LAN

The OFF state means that the system has no power, right? The apparent simplicity is deceptive. For example, the Ethernet LED is illuminated because wake-on-LAN (WOL) is enabled on your system. Check whether this is the case by typing:

$# sudo ethtool <interface name>where <interface name> might be, for example, eth0. (ethtool is found in Linux packages of the same name.) If "Wake-on" in the output shows g, remote hosts can boot the system by sending a MagicPacket. If you have no intention of waking up your system remotely and do not wish others to do so, turn WOL off either in the system BIOS menu, or via:

$# sudo ethtool -s <interface name> wol dThe processor that responds to the MagicPacket may be part of the network interface or it may be the Baseboard Management Controller (BMC).

Intel Management Engine, Platform Controller Hub, and Minix

The BMC is not the only microcontroller (MCU) that may be listening when the system is nominally off. x86_64 systems also include the Intel Management Engine (IME) software suite for remote management of systems. A wide variety of devices, from servers to laptops, includes this technology, which enables functionality such as KVM Remote Control and Intel Capability Licensing Service. The IME has unpatched vulnerabilities, according to Intel's own detection tool. The bad news is, it's difficult to disable the IME. Trammell Hudson has created an me_cleaner project that wipes some of the more egregious IME components, like the embedded web server, but could also brick the system on which it is run.

The IME firmware and the System Management Mode (SMM) software that follows it at boot are based on the Minix operating system and run on the separate Platform Controller Hub processor, not the main system CPU. The SMM then launches the Universal Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) software, about which much has already been written, on the main processor. The Coreboot group at Google has started a breathtakingly ambitious Non-Extensible Reduced Firmware (NERF) project that aims to replace not only UEFI but early Linux userspace components such as systemd. While we await the outcome of these new efforts, Linux users may now purchase laptops from Purism, System76, or Dell with IME disabled, plus we can hope for laptops with ARM 64-bit processors.

Bootloaders

Besides starting buggy spyware, what function does early boot firmware serve? The job of a bootloader is to make available to a newly powered processor the resources it needs to run a general-purpose operating system like Linux. At power-on, there not only is no virtual memory, but no DRAM until its controller is brought up. A bootloader then turns on power supplies and scans buses and interfaces in order to locate the kernel image and the root filesystem. Popular bootloaders like U-Boot and GRUB have support for familiar interfaces like USB, PCI, and NFS, as well as more embedded-specific devices like NOR- and NAND-flash. Bootloaders also interact with hardware security devices like Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs) to establish a chain of trust from earliest boot.

opensource.com

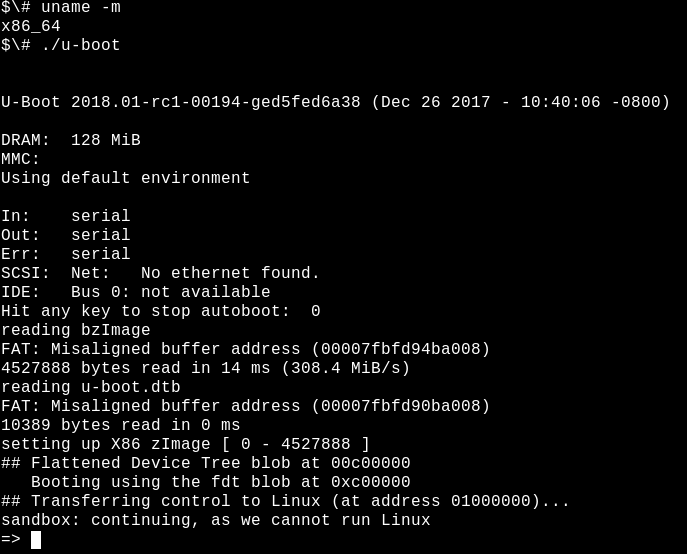

The open source, widely used U-Boot bootloader is supported on systems ranging from Raspberry Pi to Nintendo devices to automotive boards to Chromebooks. There is no syslog, and when things go sideways, often not even any console output. To facilitate debugging, the U-Boot team offers a sandbox in which patches can be tested on the build-host, or even in a nightly Continuous Integration system. Playing with U-Boot's sandbox is relatively simple on a system where common development tools like Git and the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) are installed:

$# git clone git://git.denx.de/u-boot; cd u-boot

$# make ARCH=sandbox defconfig

$# make; ./u-boot

=> printenv

=> helpThat's it: you're running U-Boot on x86_64 and can test tricky features like mock storage device repartitioning, TPM-based secret-key manipulation, and hotplug of USB devices. The U-Boot sandbox can even be single-stepped under the GDB debugger. Development using the sandbox is 10x faster than testing by reflashing the bootloader onto a board, and a "bricked" sandbox can be recovered with Ctrl+C.

Starting up the kernel

Provisioning a booting kernel

Upon completion of its tasks, the bootloader will execute a jump to kernel code that it has loaded into main memory and begin execution, passing along any command-line options that the user has specified. What kind of program is the kernel? file /boot/vmlinuz indicates that it is a bzImage, meaning a big compressed one. The Linux source tree contains an extract-vmlinux tool that can be used to uncompress the file:

$# scripts/extract-vmlinux /boot/vmlinuz-$(uname -r) > vmlinux

$# file vmlinux

vmlinux: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), statically

linked, strippedThe kernel is an Executable and Linking Format (ELF) binary, like Linux userspace programs. That means we can use commands from the binutils package like readelf to inspect it. Compare the output of, for example:

$# readelf -S /bin/date

$# readelf -S vmlinuxThe list of sections in the binaries is largely the same.

So the kernel must start up something like other Linux ELF binaries ... but how do userspace programs actually start? In the main() function, right? Not precisely.

Before the main() function can run, programs need an execution context that includes heap and stack memory plus file descriptors for stdio, stdout, and stderr. Userspace programs obtain these resources from the standard library, which is glibc on most Linux systems. Consider the following:

$# file /bin/date

/bin/date: ELF 64-bit LSB shared object, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically

linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 2.6.32,

BuildID[sha1]=14e8563676febeb06d701dbee35d225c5a8e565a,

strippedELF binaries have an interpreter, just as Bash and Python scripts do, but the interpreter need not be specified with #! as in scripts, as ELF is Linux's native format. The ELF interpreter provisions a binary with the needed resources by calling _start(), a function available from the glibc source package that can be inspected via GDB. The kernel obviously has no interpreter and must provision itself, but how?

Inspecting the kernel's startup with GDB gives the answer. First install the debug package for the kernel that contains an unstripped version of vmlinux, for example apt-get install linux-image-amd64-dbg, or compile and install your own kernel from source, for example, by following instructions in the excellent Debian Kernel Handbook. gdb vmlinux followed by info files shows the ELF section init.text. List the start of program execution in init.text with l *(address), where address is the hexadecimal start of init.text. GDB will indicate that the x86_64 kernel starts up in the kernel's file arch/x86/kernel/head_64.S, where we find the assembly function start_cpu0() and code that explicitly creates a stack and decompresses the zImage before calling the x86_64 start_kernel() function. ARM 32-bit kernels have the similar arch/arm/kernel/head.S. start_kernel() is not architecture-specific, so the function lives in the kernel's init/main.c. start_kernel() is arguably Linux's true main() function.

From start_kernel() to PID 1

The kernel's hardware manifest: the device-tree and ACPI tables

At boot, the kernel needs information about the hardware beyond the processor type for which it has been compiled. The instructions in the code are augmented by configuration data that is stored separately. There are two main methods of storing this data: device-trees and ACPI tables. The kernel learns what hardware it must run at each boot by reading these files.

For embedded devices, the device-tree is a manifest of installed hardware. The device-tree is simply a file that is compiled at the same time as kernel source and is typically located in /boot alongside vmlinux. To see what's in the binary device-tree on an ARM device, just use the strings command from the binutils package on a file whose name matches /boot/*.dtb, as dtb refers to a device-tree binary. Clearly the device-tree can be modified simply by editing the JSON-like files that compose it and rerunning the special dtc compiler that is provided with the kernel source. While the device-tree is a static file whose file path is typically passed to the kernel by the bootloader on the command line, a device-tree overlay facility has been added in recent years, where the kernel can dynamically load additional fragments in response to hotplug events after boot.

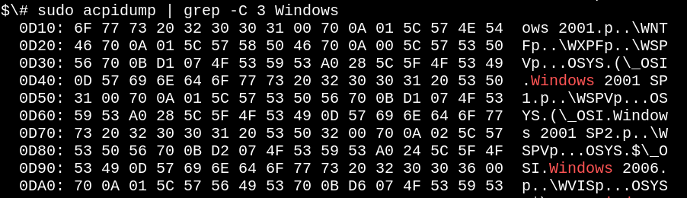

x86-family and many enterprise-grade ARM64 devices make use of the alternative Advanced Configuration and Power Interface (ACPI) mechanism. In contrast to the device-tree, the ACPI information is stored in the /sys/firmware/acpi/tables virtual filesystem that is created by the kernel at boot by accessing onboard ROM. The easy way to read the ACPI tables is with the acpidump command from the acpica-tools package. Here's an example:

opensource.com

Yes, your Linux system is ready for Windows 2001, should you care to install it. ACPI has both methods and data, unlike the device-tree, which is more of a hardware-description language. ACPI methods continue to be active post-boot. For example, starting the command acpi_listen (from package apcid) and opening and closing the laptop lid will show that ACPI functionality is running all the time. While temporarily and dynamically overwriting the ACPI tables is possible, permanently changing them involves interacting with the BIOS menu at boot or reflashing the ROM. If you're going to that much trouble, perhaps you should just install coreboot, the open source firmware replacement.

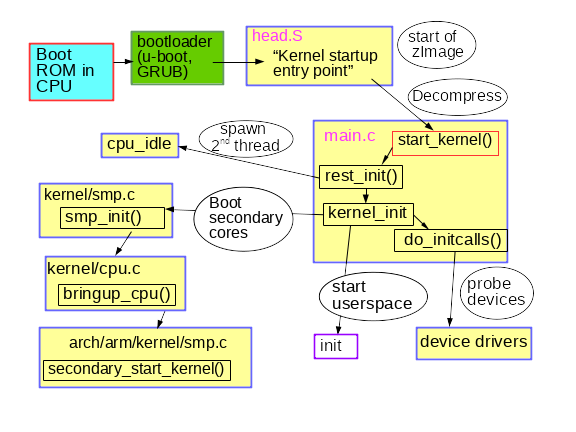

From start_kernel() to userspace

The code in init/main.c is surprisingly readable and, amusingly, still carries Linus Torvalds' original copyright from 1991-1992. The lines found in dmesg | head on a newly booted system originate mostly from this source file. The first CPU is registered with the system, global data structures are initialized, and the scheduler, interrupt handlers (IRQs), timers, and console are brought one-by-one, in strict order, online. Until the function timekeeping_init() runs, all timestamps are zero. This part of the kernel initialization is synchronous, meaning that execution occurs in precisely one thread, and no function is executed until the last one completes and returns. As a result, the dmesg output will be completely reproducible, even between two systems, as long as they have the same device-tree or ACPI tables. Linux is behaving like one of the RTOS (real-time operating systems) that runs on MCUs, for example QNX or VxWorks. The situation persists into the function rest_init(), which is called by start_kernel() at its termination.

opensource.com

The rather humbly named rest_init() spawns a new thread that runs kernel_init(), which invokes do_initcalls(). Users can spy on initcalls in action by appending initcall_debug to the kernel command line, resulting in dmesg entries every time an initcall function runs. initcalls pass through seven sequential levels: early, core, postcore, arch, subsys, fs, device, and late. The most user-visible part of the initcalls is the probing and setup of all the processors' peripherals: buses, network, storage, displays, etc., accompanied by the loading of their kernel modules. rest_init() also spawns a second thread on the boot processor that begins by running cpu_idle() while it waits for the scheduler to assign it work.

kernel_init() also sets up symmetric multiprocessing (SMP). With more recent kernels, find this point in dmesg output by looking for "Bringing up secondary CPUs..." SMP proceeds by "hotplugging" CPUs, meaning that it manages their lifecycle with a state machine that is notionally similar to that of devices like hotplugged USB sticks. The kernel's power-management system frequently takes individual cores offline, then wakes them as needed, so that the same CPU hotplug code is called over and over on a machine that is not busy. Observe the power-management system's invocation of CPU hotplug with the BCC tool called offcputime.py.

Note that the code in init/main.c is nearly finished executing when smp_init() runs: The boot processor has completed most of the one-time initialization that the other cores need not repeat. Nonetheless, the per-CPU threads must be spawned for each core to manage interrupts (IRQs), workqueues, timers, and power events on each. For example, see the per-CPU threads that service softirqs and workqueues in action via the ps -o psr command.

$\# ps -o pid,psr,comm $(pgrep ksoftirqd)

PID PSR COMMAND

7 0 ksoftirqd/0

16 1 ksoftirqd/1

22 2 ksoftirqd/2

28 3 ksoftirqd/3

$\# ps -o pid,psr,comm $(pgrep kworker)

PID PSR COMMAND

4 0 kworker/0:0H

18 1 kworker/1:0H

24 2 kworker/2:0H

30 3 kworker/3:0H

[ . . . ]where the PSR field stands for "processor." Each core must also host its own timers and cpuhp hotplug handlers.

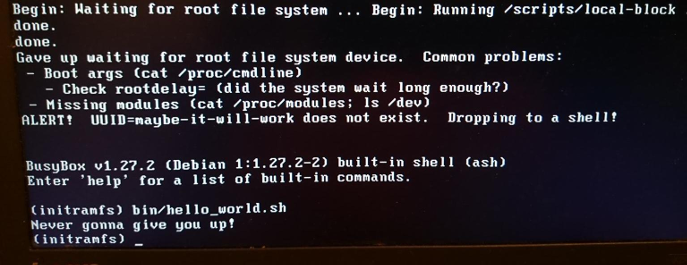

How is it, finally, that userspace starts? Near its end, kernel_init() looks for an initrd that can execute the init process on its behalf. If it finds none, the kernel directly executes init itself. Why then might one want an initrd?

Early userspace: who ordered the initrd?

Besides the device-tree, another file path that is optionally provided to the kernel at boot is that of the initrd. The initrd often lives in /boot alongside the bzImage file vmlinuz on x86, or alongside the similar uImage and device-tree for ARM. List the contents of the initrd with the lsinitramfs tool that is part of the initramfs-tools-core package. Distro initrd schemes contain minimal /bin, /sbin, and /etc directories along with kernel modules, plus some files in /scripts. All of these should look pretty familiar, as the initrd for the most part is simply a minimal Linux root filesystem. The apparent similarity is a bit deceptive, as nearly all the executables in /bin and /sbin inside the ramdisk are symlinks to the BusyBox binary, resulting in /bin and /sbin directories that are 10x smaller than glibc's.

Why bother to create an initrd if all it does is load some modules and then start init on the regular root filesystem? Consider an encrypted root filesystem. The decryption may rely on loading a kernel module that is stored in /lib/modules on the root filesystem ... and, unsurprisingly, in the initrd as well. The crypto module could be statically compiled into the kernel instead of loaded from a file, but there are various reasons for not wanting to do so. For example, statically compiling the kernel with modules could make it too large to fit on the available storage, or static compilation may violate the terms of a software license. Unsurprisingly, storage, network, and human input device (HID) drivers may also be present in the initrd—basically any code that is not part of the kernel proper that is needed to mount the root filesystem. The initrd is also a place where users can stash their own custom ACPI table code.

opensource.com

initrd's are also great for testing filesystems and data-storage devices themselves. Stash these test tools in the initrd and run your tests from memory rather than from the object under test.

At last, when init runs, the system is up! Since the secondary processors are now running, the machine has become the asynchronous, preemptible, unpredictable, high-performance creature we know and love. Indeed, ps -o pid,psr,comm -p 1 is liable to show that userspace's init process is no longer running on the boot processor.

Summary

The Linux boot process sounds forbidding, considering the number of different pieces of software that participate even on simple embedded devices. Looked at differently, the boot process is rather simple, since the bewildering complexity caused by features like preemption, RCU, and race conditions are absent in boot. Focusing on just the kernel and PID 1 overlooks the large amount of work that bootloaders and subsidiary processors may do in preparing the platform for the kernel to run. While the kernel is certainly unique among Linux programs, some insight into its structure can be gleaned by applying to it some of the same tools used to inspect other ELF binaries. Studying the boot process while it's working well arms system maintainers for failures when they come.

To learn more, attend Alison Chaiken's talk, Linux: The first second, at linux.conf.au, which will be held January 22-26 in Sydney.

Thanks to Akkana Peck for originally suggesting this topic and for many corrections.

8 Comments