On most computer systems, Linux or otherwise, when you plug a USB thumb drive in, you're alerted that the drive exists. If the drive is already partitioned and formatted to your liking, you just need your computer to list the drive somewhere in your file manager window or on your desktop. It's a simple requirement and one that the computer generally fulfills.

Sometimes, however, a drive isn't set up the way you want. For those times, you need to know how to find and prepare a storage device connected to your machine.

What are block devices?

A hard drive is generically referred to as a "block device" because hard drives read and write data in fixed-size blocks. This differentiates a hard drive from anything else you might plug into your computer, like a printer, gamepad, microphone, or camera. The easy way to list the block devices attached to your Linux system is to use the lsblk (list block devices) command:

$ lsblk

NAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINT

sda 8:0 0 238.5G 0 disk

├─sda1 8:1 0 1G 0 part /boot

└─sda2 8:2 0 237.5G 0 part

└─luks-e2bb...e9f8 253:0 0 237.5G 0 crypt

├─fedora-root 253:1 0 50G 0 lvm /

├─fedora-swap 253:2 0 5.8G 0 lvm [SWAP]

└─fedora-home 253:3 0 181.7G 0 lvm /home

sdb 8:16 1 14.6G 0 disk

└─sdb1 8:17 1 14.6G 0 partThe device identifiers are listed in the left column, each beginning with sd, and ending with a letter, starting with a. Each partition of each drive is assigned a number, starting with 1. For example, the second partition of the first drive is sda2. If you're not sure what a partition is, that's OK—just keep reading.

The lsblk command is nondestructive and used only for probing, so you can run it without any fear of ruining data on a drive.

Testing with dmesg

If in doubt, you can test device label assignments by looking at the tail end of the dmesg command, which displays recent system log entries including kernel events (such as attaching and detaching a drive). For instance, if you want to make sure a thumb drive is really /dev/sdc, plug the drive into your computer and run this dmesg command:

$ sudo dmesg | tailThe most recent drive listed is the one you just plugged in. If you unplug it and run that command again, you'll see the device has been removed. If you plug it in again and run the command, the device will be there. In other words, you can monitor the kernel's awareness of your drive.

Understanding filesystems

If all you need is the device label, your work is done. But if your goal is to create a usable drive, you must give the drive a filesystem.

If you're not sure what a filesystem is, it's probably easier to understand the concept by learning what happens when you have no filesystem at all. If you have a spare drive that has no important data on it whatsoever, you can follow along with this example. Otherwise, do not attempt this exercise, because it will DEFINITELY ERASE DATA, by design.

It is possible to utilize a drive without a filesystem. Once you have definitely, correctly identified a drive, and you have absolutely verified there is nothing important on it, plug it into your computer—but do not mount it. If it auto-mounts, then unmount it manually.

$ su -

# umount /dev/sdx{,1}To safeguard against disastrous copy-paste errors, these examples use the unlikely sdx label for the drive.

Now that the drive is unmounted, try this:

# echo 'hello world' > /dev/sdxYou have just written data to the block device without it being mounted on your system or having a filesystem.

To retrieve the data you just wrote, you can view the raw data on the drive:

# head -n 1 /dev/sdx

hello worldThat seemed to work pretty well, but imagine that the phrase "hello world" is one file. If you want to write a new "file" using this method, you must:

- Know there's already an existing "file" on line 1

- Know that the existing "file" takes up only 1 line

- Derive a way to append new data, or else rewrite line 1 while writing line 2

For example:

# echo 'hello world

> this is a second file' >> /dev/sdxTo get the first file, nothing changes.

# head -n 1 /dev/sdx

hello worldBut it's more complex to get the second file.

# head -n 2 /dev/sdx | tail -n 1

this is a second fileObviously, this method of writing and reading data is not practical, so developers have created systems to keep track of what constitutes a file, where one file begins and ends, and so on.

Most filesystems require a partition.

Creating partitions

A partition on a hard drive is a sort of boundary on the device telling each filesystem what space it can occupy. For instance, if you have a 4GB thumb drive, you can have a partition on that device taking up the entire drive (4GB), two partitions that each take 2GB (or 1 and 3, if you prefer), three of some variation of sizes, and so on. The combinations are nearly endless.

Assuming your drive is 4GB, you can create one big partition from a terminal with the GNU parted command:

# parted /dev/sdx --align opt mklabel msdos 0 4GThis command specifies the device path first, as required by parted.

The --align option lets parted find the partition's optimal starting and stopping point.

The mklabel command creates a partition table (called a disk label) on the device. This example uses the msdos label because it's a very compatible and popular label, although gpt is becoming more common.

The desired start and end points of the partition are defined last. Since the --align opt flag is used, parted will adjust the size as needed to optimize drive performance, but these numbers serve as a guideline.

Next, create the actual partition. If your start and end choices are not optimal, parted warns you and asks if you want to make adjustments.

# parted /dev/sdx -a opt mkpart primary 0 4G

Warning: The resulting partition is not properly aligned for best performance: 1s % 2048s != 0s

Ignore/Cancel? C

# parted /dev/sdx -a opt mkpart primary 2048s 4GIf you run lsblk again (you may have to unplug the drive and plug it back in), you'll see that your drive now has one partition on it.

Manually creating a filesystem

There are many filesystems available. Some are free and open source, while others are not. Some companies decline to support open source filesystems, so their users can't read from open filesystems, while open source users can't read from closed ones without reverse-engineering them.

This disconnect notwithstanding, there are lots of filesystems you can use, and the one you choose depends on the drive's purpose. If you want a drive to be compatible across many systems, then your only choice right now is the exFAT filesystem. Microsoft has not submitted exFAT code to any open source kernel, so you may have to install exFAT support with your package manager, but support for exFAT is included in both Windows and MacOS.

Once you have exFAT support installed, you can create an exFAT filesystem on your drive in the partition you created.

# mkfs.exfat -n myExFatDrive /dev/sdx1Now your drive is readable and writable by closed systems and by open source systems utilizing additional (and as-yet unsanctioned by Microsoft) kernel modules.

A common filesystem native to Linux is ext4. It's arguably a troublesome filesystem for portable drives since it retains user permissions, which are often different from one computer to another, but it's generally a reliable and flexible filesystem. As long as you're comfortable managing permissions, ext4 is a great, journaled filesystem for portable drives.

# mkfs.ext4 -L myExt4Drive /dev/sdx1Unplug your drive and plug it back in. For ext4 portable drives, use sudo to create a directory and grant permission to that directory to a user and a group common across your systems. If you're not sure what user and group to use, you can either modify read/write permissions with sudo or root on the system that's having trouble with the drive.

Using desktop tools

It's great to know how to deal with drives with nothing but a Linux shell standing between you and the block device, but sometimes you just want to get a drive ready to use without so much insightful probing. Excellent tools from both the GNOME and KDE developers can make your drive prep easy.

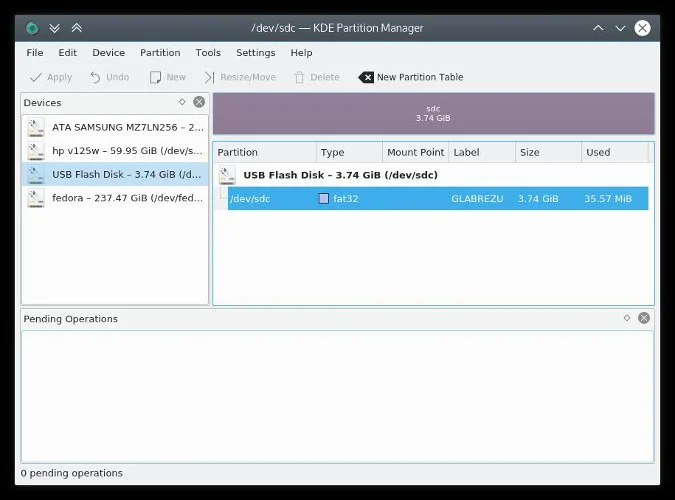

GNOME Disks and KDE Partition Manager are graphical interfaces providing an all-in-one solution for everything this article has explained so far. Launch either of these applications to see a list of attached devices (in the left column), create or resize partitions, and create a filesystem.

KDE Partition Manager

The GNOME version is, predictably, simpler than the KDE version, so I'll demo the more complex one—it's easy to figure out GNOME Disks if that's what you have handy.

Launch KDE Partition Manager and enter your root password.

From the left column, select the disk you want to format. If your drive isn't listed, make sure it's plugged in, then select Tools > Refresh devices (or F5 on your keyboard).

Don't continue unless you're ready to destroy the drive's existing partition table. With the drive selected, click New Partition Table in the top toolbar. You'll be prompted to select the label you want to give the partition table: either gpt or msdos. The former is more flexible and can handle larger drives, while the latter is, like many Microsoft technologies, the de-facto standard by force of market share.

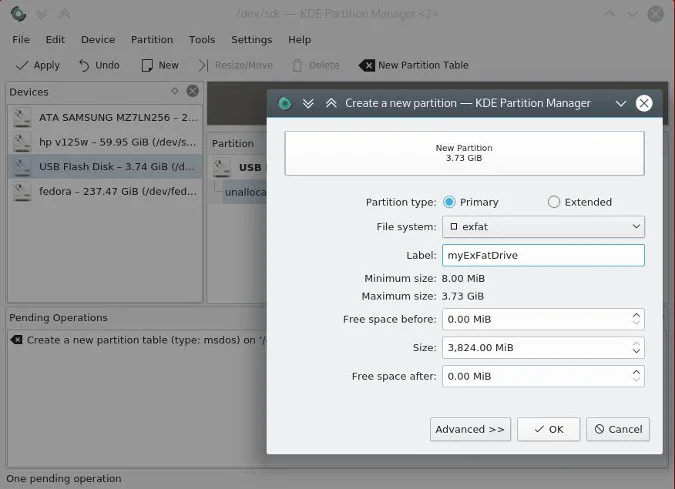

Now that you have a fresh partition table, right-click on your device in the right panel and select New to create a new partition. Follow the prompts to set the type and size of your partition. This action combines the partitioning step with creating a filesystem.

Creating a new partition

To apply your changes to the drive, click the Apply button in the top-left corner of the window.

Hard drives, easy drives

Dealing with hard drives is easy on Linux, and it's even easier if you understand the language of hard drives. Since switching to Linux, I've been better equipped to prepare drives in whatever way I want them to work for me. It's also been easier for me to recover lost data because of the transparency Linux provides when dealing with storage.

Here are a final few tips, if you want to experiment and learn more about hard drives:

- Back up your data, and not just the data on the drive you're experimenting with. All it takes is one wrong move to destroy the partition of an important drive (which is a great way to learn about recreating lost partitions, but not much fun).

- Verify and then re-verify that the drive you are targeting is the correct drive. I frequently use lsblk to make sure I haven't moved drives around on myself. (It's easy to remove two drives from two separate USB ports, then mindlessly reattach them in a different order, causing them to get new drive labels.)

- Take the time to "destroy" a test drive and see if you can recover the data. It's a good learning experience to recreate a partition table or try to get data back after a filesystem has been removed.

For extra fun, if you have a closed operating system lying around, try getting an open source filesystem working on it. There are a few projects working toward this kind of compatibility, and trying to get them working in a stable and reliable way is a good weekend project.

Comments are closed.