Running software is something that most of us do without thinking about it. We run in "on premises"—our own machines—or we run it in the cloud - on somebody else's machines. We don't always think about what those differences mean, or about what assumptions we're making about the security of the data that's being processed, or even of the software that's doing that processing. Specifically, when you run software (a "workload") on a system (a "host") on the cloud or on your own premises, there are lots and lots of layers. You often don't see those layers, but they're there.

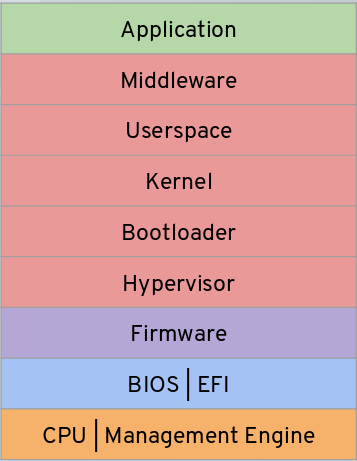

Here's an example of the layers that you might see in a standard cloud virtualisation architecture. The different colours represent different entities that "own" different layers or sets of layers.

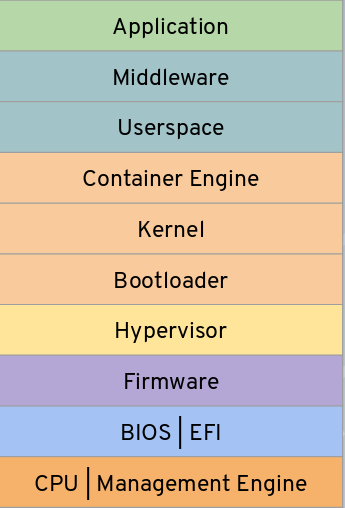

Here's a similar diagram depicting a standard cloud container architecture. As before, each different colour represents a different "owner" of a layer or set of layers.

These owners may be of very different types, from hardware vendors to OEMs to cloud service providers (CSPs) to middleware vendors to operating system vendors to application vendors to you, the workload owner. And for each workload that you run, on each host, the exact list of layers is likely to be different. And even when they're the same, the versions of the layers instances may be different, whether it's a different BIOS version, a different bootloader, a different kernel version, or whatever else.

Now, in many contexts, you might not worry about this, and your CSP goes out of its way to abstract these layers and their version details away from you. But this is a security article, for security people, and that means that anybody who's reading this probably does care.

The reason we care is not just the different versions and the different layers, but the number of different things—and different entities—that we need to trust if we're going to be happy running any sort of sensitive workload on these types of stacks. I need to trust every single layer, and the owner of every single layer, not only to do what they say they will do, but also not to be compromised. This is a big stretch when it comes to running my sensitive workloads.

What's Enarx?

Enarx is a new project that is trying to address this problem of having to trust all of those layers. A few of us at Red Hat have been working on it for a few months now. My colleague Nathaniel McCallum demoed an early incarnation of it at Red Hat Summit 2019 in Boston, and we're ready to start announcing it to the world. We have code, we have a demo, we have a GitHub repository, we have a logo: what more could a project want? Well, people—but we'll get to that.

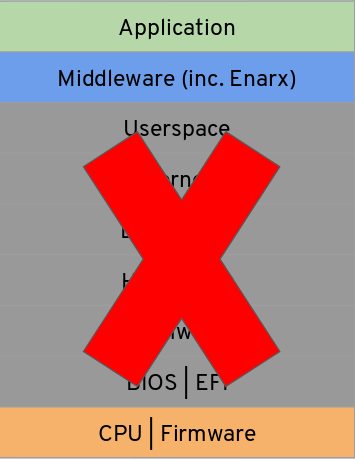

With Enarx, we made the decision that we wanted to allow people running workloads to be able to reduce the number of layers—and owners—that they need to trust to the absolute minimum. We plan to use trusted execution environments ("TEEs"—see "Oh, how I love my TEE (or do I?)") to provide an architecture that looks a little more like this:

In a world like this, you have to trust the CPU and firmware, and you need to trust some middleware—of which Enarx is part—but you don't need to trust all of the other layers, because we will leverage the capabilities of the TEE to ensure the integrity and confidentiality of your application. The Enarx project will provide attestation of the TEE, so that you know you're running on a true and trusted TEE, and will provide open source, auditable code to help you trust the layer directly beneath your application.

The initial code is out there—working on AMD's SEV TEE at the moment—and enough of it works now that we're ready to tell you about it.

Making sure that your application meets your own security requirements is down to you. :-)

How do I find out more?

The easiest way to learn more is to visit the Enarx GitHub.

We'll be adding more information there—it's currently just code—but bear with us: there are only a few of us on the project at the moment. A blog is on the list of things we'd like to have, but we wanted to get things started.

We'd love to have people in the community getting involved in the project. It's currently quite low-level and requires quite a lot of knowledge to get running, but we'll work on that. You will need some specific hardware to make it work, of course. Oh, and if you're an early boot or a low-level KVM hacker, we're particularly interested in hearing from you.

I will, of course, respond to comments on this article.

This article was originally published on Alice, Eve, and Bob and is reprinted with the author's permission.

2 Comments