These days, we all have a few dozen passwords. Fortunately, the bulk of those passwords are probably for websites, and you probably access most websites through your internet browser, and most browsers have a built-in password manager. The most common internet browsers also have a synchronization feature to help you distribute your passwords between the browsers you run across all your devices, so you're never without your login information when you need it. If that's not enough for you, there are excellent open source projects like BitWarden that can host your encrypted passwords, ensuring that only you have the key to unlock them. These solutions help make maintaining unique passwords easy, and I use these convenient systems for a selection of passwords. But my main vault of password storage is a lot simpler than any of these methods. I primarily use pass, a classic UNIX-style password management system that uses GnuPG (GPG) for encryption, and the terminal as its primary interface.

Install pass

You can install the pass command from your distribution repository.

On Fedora, Mageia, and similar distributions, you can install it with your package manager:

$ sudo dnf install passOn Elementary, Mint, and other Debian-based distributions:

$ sudo apt install passOn macOS, you can install it using Homebrew:

$ brew install passConfiguring GnuPG

Before you can use pass, you need a valid PGP ("Pretty Good Privacy") key. If you already maintain a PGP key, you can skip this step, or you can choose to create a new key exclusively for use with pass. The most common open source PGP implementation is GnuPG (GPG), which ships with Linux, and you can install it on macOS from gpgtools.org, Homebrew, or Macports. To create a GnuPG key, run this command:

$ gpg --generate-key

You're prompted for your name and email address and create a password for the key. Your key is a digital file, and your password is known only to you. Combined, these two things can lock and unlock encrypted information, such as a file containing a password.

A GPG key is much like a house key or a car key. Should you lose it, anything locked by it becomes unobtainable. Just knowing your password is not enough.

If you already manage several SSH keys, you're probably used to this. If you're new to digital encryption keys, it can take some getting used to. Backup your ~/.gnupg directory, so you don't accidentally erase it the next time you decide to try an exciting new distro on a whim.

Make a backup and keep the backup safe.

Configuring pass

To start using pass, you must initialize a password store, which is defined as a storage location configured to use a specific encryption key. You can indicate what GPG key you want to use for your password store by either the name associated with the key or the digital fingerprint. Your own name is usually the easier option:

$ pass init seth

mkdir: created directory '/home/seth/.password-store/'

Password store initialized for sethIf you've managed to forget your name, you can see the digital fingerprint and name associated with your key with the gpg command:

$ gpg --list-keys

gpg --list-keys

/home/seth/.gnupg/pubring.kbx

-----------------------------

pub ed25519 2022-01-06 [SC] [expires: 2024-01-06]

2BFF94286461216C907CBA52F067996F13EF10D8

uid [ultimate] Seth Kenlon <seth@example.com>

sub cv25519 2022-01-06 [E] [expires: 2024-01-06]Initializing a password store with the fingerprint is basically the same as with your name:

$ pass init 2BFF94286461216C907CBA52F067996F13EF10D8Store a password

Add a password to your password store with the pass add command:

$ pass add www.example.com

Enter password for www.example.com:Enter the password you want to add when prompted.

The password now gets stored in your password store. You can take a look for yourself:

$ ls /root/.password-store/

www.example.com.gpgOf course, the file is unreadable, and if you attempt to run cat or less on it, you'll get unprintable characters in your terminal (use reset to fix your terminal if its display gets too untidy.)

Edit a password with pass

I use different user names for different activities online, so the username for a site is often just as important as the password. The pass system allows for this, even though it doesn't prompt you for it by default. You can add a user name to a password file using the pass edit command:

$ pass edit www.example.comThis opens a text editor (specifically the editor you have set as your EDITOR or VISUAL environment variable) displaying the contents of the www.example.com file. Currently, that's just a password, but you can add a user name and even another URL or any information you want. It's an encrypted file, so you're free to keep what you want in it.

bd%dc$3a49af49498bb6f31bc964718C

user: seth123

url: example.comSave the file and close it.

Get a password from pass

To see the contents of a password file, use the pass show command:

$ pass show www.example.com

bd%dc$3a49af49498bb6f31bc964718C

user: seth123

url: www.example.orgSearch for a password

Sometimes it's tough to remember whether a password is filed under www.example.com or just example.com or even something like app.example.com. Furthermore, some website infrastructures use different URLs for different site functions, so you might file a password away under www.example.com even though you also use the same login information for the partner site www.example.org.

When in doubt, use grep. The pass grep command shows all instances of a search term, either in a file name or in the contents of a file:

$ pass grep example

www.example.com:

url: www.example.orgUsing pass with a browser

I use pass for information beyond just internet passwords, but websites are where I most often need passwords. I usually have a terminal open somewhere on my computer, so it's not much trouble to Alt+Tab to a terminal and get the information I need with pass. But that's not what I do because there are plugins to integrate pass with web browsers.

Pass host script

First, install the pass host script:

$ curl -sSL github.com/passff/passff-host/release/latest/download/install_host_app.shThis install script places a Python script that helps your browser access your password store and GPG keys. Run it along with the name of the browser you use (or nothing, to see all options):

$ bash ./install_host_app.sh firefoxIf you use multiple browsers, you can install it for each.

Pass Add-on

Once you've installed the host application, you can install an add-on or extension for your browser. Search for the PassFF plugin in your browser's add-on or extension manager.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Install the add-on, and then close and re-launch your browser.

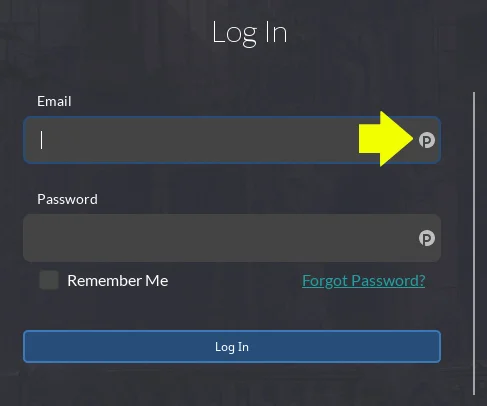

Navigate to a site you've got a password for in your password store. There's now a small P icon in the right of your login text fields.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

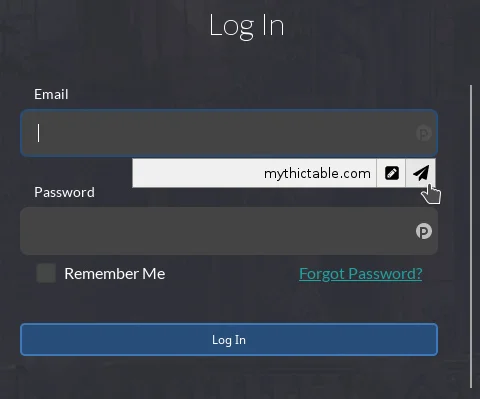

Click on the P button to see a list of matching site names in your password store.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Click the pen-and-paper icon to fill in the form or the paper-airplane icon to fill and auto-submit the form.

Easy password management and fully integrated!

Try pass as your Linux password manager

The pass command is a great option for users who want to manage passwords and personal information using tools they already use on a daily basis. If you rely on GPG and a terminal already, then you may enjoy the pass system. It's also an important option for users who don't want their passwords tied to a specific application. Maybe you don't use just one browser, or you don't like the idea that it might be difficult to extract your passwords from an application if you decide to stop using it. With pass, you maintain control of your secrets in a UNIX-like and straightforward system.

Comments are closed.