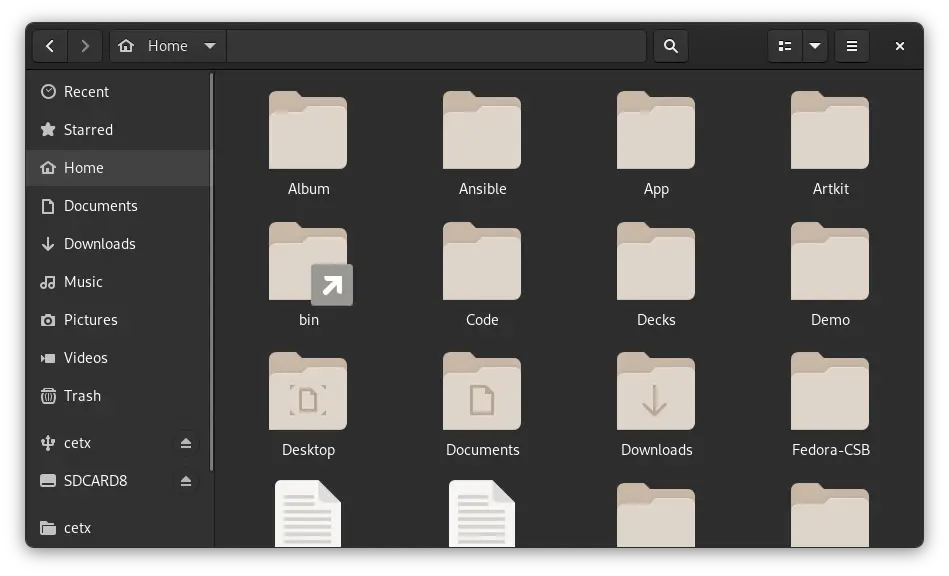

The GNOME desktop is a common default desktop for most Linux distributions and, as with most operating systems, you manage your data on GNOME with software called a file manager. GNOME promotes a simple and clear naming scheme for its applications, and so its file manager is called, simply, Files. Its intuitive interface is simple enough that you forget what operating system you're using altogether. You're just using a computer, managing files in the most obvious way. GNOME Files is a shining example of thoughtful, human-centric design, and it's an integral part of modern computing. These are my top five favorite things about GNOME Files, and why I love using it.

1. Intuitive design

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

As long as you've managed files on a computer before, you basically already know how to use GNOME Files. Sure, everybody loves innovation, and everybody loves seeing new ideas that make the computer world a little more exciting. However, there's a time and a place for everything, and frankly sometimes the familiar just feels better. Good file management is like breathing. It's something you do without thinking about what you're doing. When it becomes difficult for any reason, it's disruptive and uncomfortable.

GNOME Files doesn't have any surprises in store for you, at least not the kind that make you stop what you thought you were doing in order to recalculate and start again. And my favorite aspect of the "do it the way you think you should do it" design of GNOME Files is that there isn't only one way to accomplish a task. One thing I've learned from teaching people how to do things on computers is that everyone seems to have a slightly different workflow for even the simplest of tasks, so it's a relief that GNOME Files accounts for that.

When you need to move a file, do you open a second window so you can drag and drop between the two? Or do you right-click and Cut the file and then navigate to the destination and Paste the file? Or do you drag the file onto a button or folder icon, blazing a trail through directories as they open for you? In GNOME Files, the "standard" assumptions usually apply (insofar as there are standard assumptions.)

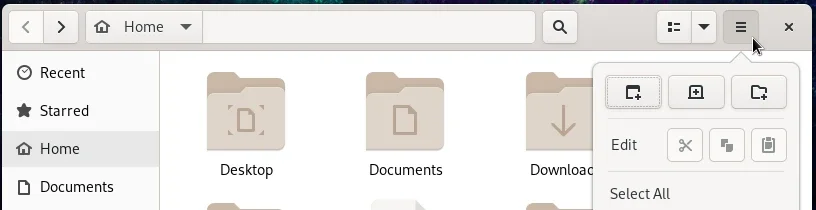

2. Space saver

If you manage a lot of files for a lot of the time you're at your computer, you're probably familiar with just how much screen real estate a file manager can take up. Many file managers have lots of buttons across several toolbars, a menu bar, and a status bar, such that just one file manager window takes up a good portion of your screen. To make matters worse, many users prefer to open several folders, each in its own window, which takes even more space.

GNOME Files tends to optimize space. What takes up three separate toolbars in other file managers is in a single toolbar in GNOME Files, and that toolbar is what would traditionally be the window title bar. In the top bar, there's a forward and back button, file path information, a view settings button, and a drop-down menu with access to common functions.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

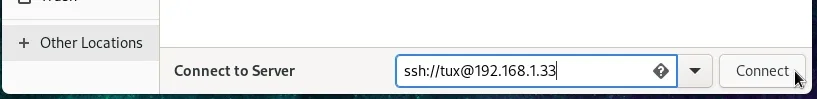

3. Other locations

Not all operating systems or file managers make it so you can interact with your network as naturally as you can interact with your own computer. Linux has a long tradition of viewing the network as just another computer, and in fact, the name "GNOME" was an acronym for "GNU Network Object Model Environment."

In GNOME Files, it's trivial to open a folder on a computer you're not sitting in front of. Whether it's a server in a data center or just your office desktop while you're relaxing in your lounge with a laptop, the Other Locations bookmark in the GNOME Files side panel allows you to access files as if they were on your hard drive.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

To use it, you enter the file sharing protocol you want to use, along with the username and IP address of the computer you want to access. The ssh:// protocol is most common between Linux or Unix machines, while smb:// is useful for an environment with Windows machines, and dav:// is useful for applications running on the Internet. Assuming the target computer is accessible over the protocol you're using, and that its firewall is set correctly to permit you to pass through it, you can interact with a remote system as naturally as though they were on your local machine.

4. Preferences

Most file managers have configuration options, and to be fair GNOME Files actually doesn't give you very many choices compared to others. However, the options that it does offer are, like the modes of working it offers its users, the "standard" ones. I'm misusing the word "standard" intentionally: There is no standard, and what feels standard to one person is niche to someone else. But if you like what you're experiencing with GNOME Files under normal circumstances, and you feel that you're its intended audience, then the configuration options it offers are in line with the experience it promotes. For example:

-

Sort folders before files

-

Expand folders in list view

-

Show the Create link option in the contextual menu

-

Show the Delete Permanently option in the contextual menu

-

Adjust visible information beneath a filename in icon view

That's nearly all the options you're given, and in a way it's surface-level choices. But that's GNOME Files. If you want something with more options, there are several very good alternatives that may better fit your style of work. If you're looking for a file manager that just covers the most common use cases, then try GNOME Files.

5. It's full of stars

I love the concept of metadata, and I generally hate the way it's not implemented. Metadata has the potential to be hugely useful in a pragmatic way, but it's usually relegated to specialized metadata editing applications, hidden from view and out of reach. GNOME Files humbly contributes to improving this situation with one simple feature: The gold star.

In GNOME Files, you can star any file or folder. It's a bit of metadata so simple that it's almost silly to call it metadata, but in my experience, it makes a world of difference. Instead of desperately running find command to filter files by recent changes, or re-sorting a folder by modification time, or using grep to find that one string I just know is in an important file, I can star the files that are important to me.

Making plans for the zombie apocalypse all day? Star it so you can find it tomorrow when you resume your important work. After it's over and the brain-eaters have been dealt with, un-star the folder and resume normal operation. It's simple. Maybe too simple for some. But I'm a heavy star-user, and it saves me several methods of searching and instead reduces "what was I working on?" to the click of a single button.

Install GNOME Files

If you've downloaded a mainstream Linux distribution, then chances are good that you already have GNOME and GNOME Files installed. However, not all distributions default to GNOME, and even those that do often have different desktops available for download. The development name of GNOME Files is nautilus, so to find out whether you have GNOME Files installed, open a terminal and type nautilus & and then press Return. If you see this error, you don't have GNOME Files available:

bash: nautilus: command not found...To install GNOME Files, you must install the GNOME desktop. If you're happy with your current desktop, though, that's probably not what you want to do. Instead, consider trying PCManFM or Thunar.

If you're interested in GNOME, though, this is a great reason to try it. You can probably install GNOME from your distribution's repository or software center.

Comments are closed.