Computers are like filing cabinets, full of virtual folders and files waiting to be referenced, cross-referenced, edited, updated, saved, copied, moved, renamed, and organized. In this article, I'll look at a file manager for your Linux system.

Back before NVMe drives and 12-core processors, applications could take seconds to launch. While that wait time is fine for a big application like LibreOffice or Blender, it's a little painful when it's a tiny application you use frequently. 2 seconds times 10 file manager windows in an hour, times 12 hours a day, is 4 whole minutes of wasted time. OK, I admit that's actually not that much when you do the math, but ask anybody and they'll tell you that it felt like 4 hours. One way to make a computer, whether it's last year's model or something hot off the shelf, feel faster is to use "lightweight" applications. An application is usually considered lightweight when it's designed around minimal code libraries that don't demand much from your system's resources.

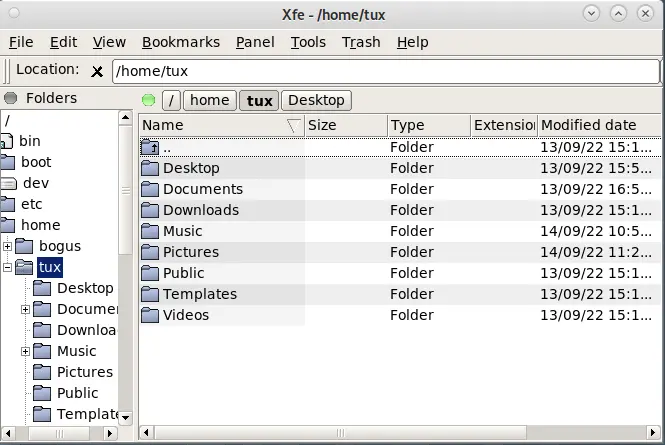

The X File Explorer (Xfe) file manager is one of those applications. It's quick to launch, it doesn't feature fancy animations or effects, and it has few dependencies beyond some basic libraries, most of which are probably already on your Linux system.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Install on Linux

On Fedora, CentOS, Mageia, and similar, you can install Xfe from your software repository:

$ sudo dnf install xfeOn Debian, Elementary, Linux Mint, and similar:

$ sudo apt install xfe xfe-themesXfe is open source, so you can alternately just download the source code and compile it yourself.

Using Xfe

The first thing you're likely to notice about Xfe is that by default it's a little top-heavy. There's a menu bar, and then not one but five toolbars along the top of the window. Those toolbars aren't hard coded in position, though, and you can choose which toolbar you actually need on screen at all times in the View menu. Personally, I keep the Location toolbar on and hide the rest. But I think all Xfe users are likely to have a favorite set of toolbars all their own, so when you first try Xfe give yourself time to see which toolbar you actually end up using.

Here's a list of the toolbars and some of the important buttons they each contain:

-

General: Navigation buttons, view refresh, new file, new directory, copy, cut, paste, and other standard file manager actions. This could replace the menu bar, were there a way to hide the menu bar.

-

Tools: Launch a new Xfe window as user or root, execute a command, launch a terminal.

-

Panel: Split the Xfe window into two panes, two panes with panels, one pane with panel, or a single pane.

-

Location: Enter a path for quick navigation.

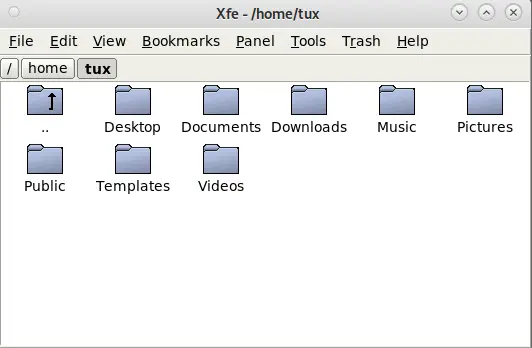

It's not just the toolbars that are configurable. You can hide most components of Xfe, including the side pane displaying your filesystem tree and the status bar. Xfe can look as minimal as its memory footprint:

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Power menu

The beautiful thing about Xfe's design is that you never sacrifice features regardless of your configuration. You can hide toolbars and panels, but you still have access to every option from the menu.

From the Panel menu, for instance, you can filter files by regex strings, show hidden files, activate and deactivate thumbnails (the fewer things your computer has to render, the faster it can draw the screen), switch icon views between a list or detailed list, choose to ignore case, reverse the sort order, and more.

There's even a menu for the Trash, so you can always get to the place you need to be to rescue something you've thrown out.

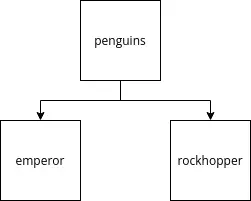

Two dots

The feature I appreciate more than I'd expected I would is Xfe's inclusion of a meta folder with a name of just two dots. The .. folder isn't really a folder. It's shorthand for going "up" in your directory tree. If you don't think of folders existing in a tree configuration, that might not make immediate sense, but in computing, you can express the hierarchy of data storage in the same way you might express a family tree. If the penguins folder contains the emperor and rockhopper folders, then you can think of the penguin directory as their "parent."

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Computers use two dots as an instruction to move out of the current directory and "up" the tree. When you're in the rockhopper folder, two dots mean ascend up to penguins. When you're in the emperor folder, two dots also mean ascend up to penguins, because emperor and rockhopper are both "children" of the penguins directory.

This two dot convention is common in Linux and in fact the entire Internet (you can test this out by appending /.. to the end of the URL of this article. It won't get you very far due to restricted permissions, but it does successfully take you off this page, so wait until you're done reading!) Having access to two dots in every directory of Xfe is a familiar and convenient way to navigate.

Make it quick

Running fast applications makes your computing faster. It's a secret that experienced Linux users have known for years, and it's one of the many reasons you often see Linux users with ancient computers. When you use a terminal and a handful of lightweight applications, even a computer from a decade ago doesn't feel slow. The Xfe file manager, whether you use it for speed or just because it's a reliable app that's got everything you need, is an excellent choice for a file manager.

Comments are closed.