The story is told like this: A university constructs several new buildings on its campus. But rather than build sidewalks between buildings, they plant grass, let people walk, and wait. Pedestrians choose the most efficient paths--and over time the lines worn in the grass reveal where sidewalks should be.

I first heard this story about seven years ago, and it has been used to describe universities like University of California Davis and Dartmouth. I’m not sure how many of these stories are more folklore than fact. Some sites claim the stories happened; others claim them to be urban legend.

Regardless. It’s a brilliant idea. And more recently I’ve heard there is an actual name in landscape architecture to describe it: desire lines. Or, as it’s also known, a desire path.

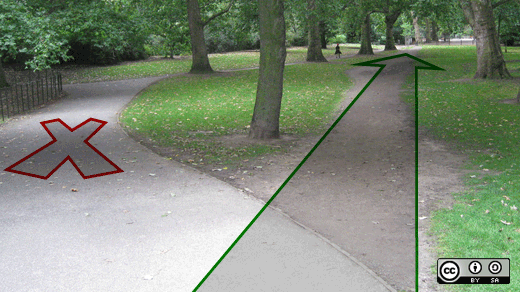

It’s a path created by people over time who are making it clear where they naturally desire to go, rather than where they're being directed.

It's a beautiful example of the principle of emergence--allowing patterns to emerge out of natural behavior rather than forced unnaturally. But it's also an example of the open source way.

One of the primary open source principles at work here is meritocracy, or letting the best ideas win. When you create an open environment where people are allowed to have ideas passed freely and communication in the open, these natural paths can start to appear. Paths form, the best ideas emerge.

I first became interested in the idea when I read the Steven Johnson book Emergence. In the book Johnson uses the behavior of ants and the design of cities to describe how these natural patterns emerge over time.

Since the writing of the book in 2002, the web has come to resemble so many properties of emergence at warp speed. Just look at trending topics on Twitter. Or any video on Youtube with hits in the hundreds of millions--even though it started as just another parent uploading a video of their kid biting his brother’s finger.

How can you take advantage of desire lines in your own organization?

First, you have to create an environment where people can share their ideas and work out in the open. When you can see the work, you can see the patterns they leave over time. In this environment, people aren’t afraid to share their best ideas and self-select from among many available choices.

This is one of the reasons why we use the design thinking process to generate ideas. Design thinking creates a safe, open environment that allows people to share ideas, then offers some clear paths to help those ideas emerge. One of the key rules of design thinking sessions are that many and all ideas are welcome, and titles should be left at the door. It’s from many ideas and from diverse perspectives that the best ideas happen.

Second, you have to know where to look, and how, to watch those patterns emerge. Maybe it’s mailing lists or on wikis or other collaboration tools. What do they tell you about what’s working? They may not only only reveal which ideas people are gravitating toward through traffic and activity metrics, but how work is getting done. Are there names that seem to keep appearing over and over? If people in your organization are consistently finding a path of least resistance when they’re most effective, it’s time to look at why...

- What parts of the process are allowing people be most effective time and again?

- Are there catalysts in your organization you don’t know about? Does it seem like a lot of work and ideas originate or go through the same people?

- Are there properties present in your most effective teams?

- Are there problems and roadblocks that keep getting repeated in your organization? Can you break down the artificial barriers that stand between your people discovering their own, more efficient paths?

Third, shine a light where things are going right so they can be repeated by others. Tell their stories and celebrate them. The other inefficient paths, even the dead ends--you can learn from those, too, and you should. They key is to share what you're learning and make that knowledge visible.

And when those paths become clear, then it’s time to build your sidewalks.

2 Comments