In proprietary software, the company contributes 100% of the code. If you think about a traditional proprietary software product, it has a development community of one: the software company itself. The company’s ability to support that product, to influence the features that come in future versions, and to integrate that product with other products in its ecosystem flows directly from its direct control over the source code and its development.

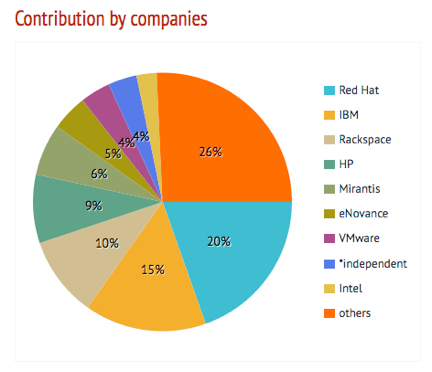

In open source, it is rare that any one company controls anything close to 100% of the source code; in fact, it is often a sign of a weak open source community if one company dominates a project. The power and the value of the open source development model come from many individual and corporate contributors coming together. Using this thinking, we can look at the collaborative corporate contributions to OpenStack.

Corporate OpenStack contributions: Four key questions

One very basic way to look at the corporate contributions to OpenStack is analyze the aggregate contributions to all of the core projects that make up OpenStack:

Source: Stackalytics.com

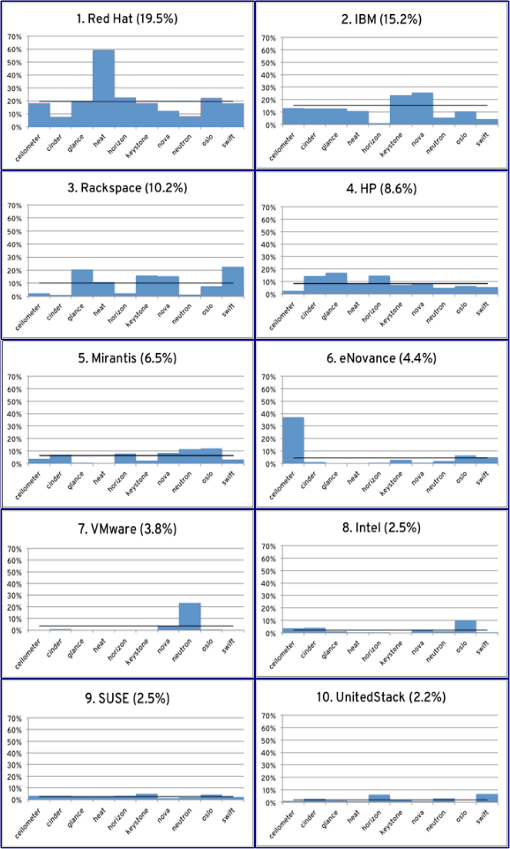

But, as some have pointed out, this can quickly become an exercise in “vanity statistics.” What is the real value to enterprise customers of contributions to the community? Is it best to judge an organization’s participation in a project by raw commits, or is there another measure that better represents involvement. In a multi-part project like OpenStack, the breadth of projects contributed to might also be a telling statistic.

Looking beyond the ranking to this kind of a heat map of participation gives a more nuanced way of considering:

- What core projects are particular companies focusing on?

- Which companies are participating broadly across the projects?

- What are the gaps in OpenStack knowledge and participation of a particular company?

- Does a company’s investment in the OpenStack community match the products or services they are selling?

Let’s consider contributions to all of the projects that were considered “core” in OpenStack Havana:

- Ceilometer (OpenStack Telemetry)

- Cinder (OpenStack Block Storage)

- Glance (OpenStack Image Service)

- Heat (OpenStack Orchestration)

- Horizon (OpenStack Dashboard)

- Keystone (OpenStack Identity)

- Nova (OpenStack Compute)

- Neutron (OpenStack Networking)

- Oslo (OpenStack Common Libraries)

- Swift (OpenStack Object Storage)

What’s a better way to visualize a company’s participation in OpenStack beyond the aggregate rankings? If we take each company’s contribution to the lastest OpenStack release, Havana, (in this case, by number of commits) and express it as a percentage of the total contribution, and then look at it across these projects, the plot for the top ten contributors look like this:

Source: Stackalytics.com

Participation matters in open source

Perhaps it does not matter if you are using the free OpenStack code on a free Linux distribution. But if you are paying for an OpenStack product, or you are looking to move from a proof-of-concept to a production OpenStack environment, then I believe that community participation really does matter.

It’s not just about who is the top contributor. Does any OpenStack vendor really have the expertise to support your production OpenStack environment? Can an OpenStack vendor be a strategic partner for the long term in driving your requirements into future versions of their OpenStack product? These are questions similar to those that enterprise customers were asking ten years ago when they moved from Linux proof of concepts to running real workloads on Linux systems. And they are questions worth considering again as OpenStack begins to appear in the datacenter.

Originally posted on Red Hat Stack: An OpenStack Blog. Reposted with permission.

8 Comments