As individual job tenure in companies becomes shorter, leaders say goodbye to even their best people more frequently. How they do this—whether they celebrate or shun the departed—affects not just those leaving but those who stay, as well as the performance of both the old and new firms.

Companies that maintain alumni networks are in a better position to leverage a principle that sociologists call "embeddedness." Every industry is a network of connections: companies, clients, vendors, competitors, and partners. Embeddedness refers to a company's location in the larger network. And location matters: research shows that the strength of a company's relationships to other entities in the industry directly affects that company's financial strength.

This effect was first uncovered by Brian Uzzi in research he conducted early in his career. In fact, it was his doctoral dissertation. Uzzi decided to study the garment industry in New York City, a complex network that he was already a little familiar with. "When my family came over here [the United States] from Italy, they both went into the needle trade. My grandfather was a tailor; my mother went to sewing school," he recalled. Uzzi knew that the New York City garment industry was a network ripe for study, and he knew that different company leaders interacted differently. What he wanted to find out was whether their actions in the network made a difference for their company.

Uzzi studied twenty-three apparel firms in New York City and conducted interviews with each company's CEO and other key executives. He also observed interactions with company employees and distributors, customers, suppliers, and competitors. In addition, he gathered information on company transactions through the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), the trade union to which over 80 percent of New York's better apparel firms belonged. The union kept records on the volume of exchanges between different firms in the industry. Uzzi also modeled the likelihood of failure for each firm in the industry against his research on the companies, based on the number of firms that failed during the calendar year of his research. When he analyzed all of his research and compared a firm's network interactions with its likelihood of failure, Uzzi found something surprising.

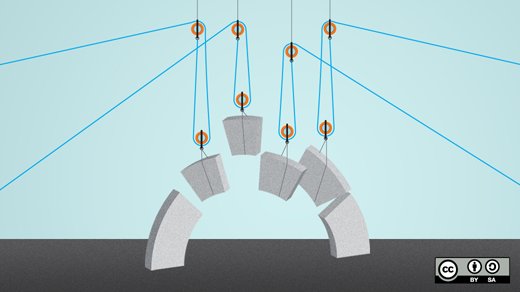

As he suspected, different firms interacted in the industry differently, and the differences mattered. "Embedded networks of organizations achieve a certain competitive advantage over market arrangements," Uzzi wrote in his article on the research. Some firms did business with only a few trusted vendors (what Uzzi labeled "close-knit ties"), while others portioned out their business by giving many small assignments to various firms ("arm's-length ties"). He found that having strong close-knit ties did increase a firm's chances of survival—but only to a point before being too close with too few firms began to have a negative impact.

The firms with the most success in the industry maintained a solid mix of close-knit and arm's-length ties and selectively chose which ties to use when. "There's this balance between having arm's-length ties that don't go as deeply into the relationship, but allow you to scan the market more broadly," Uzzi explained. "At the same time, the energy spent that you might put into a close-knit tie could have been split up among or across many arm's-length ties. That allows you to get information from many different points of view and then integrate it to produce the very best benefit."

A firm that is too distant from other firms in the industry can't leverage the benefits of trust or get help to solve the challenges they might face. At the same time, being too close to only a few firms prevents the individual company from getting enough new market information and being adaptive to changes in the industry.

That balance between close-knit and arm's-length ties is exactly what an alumni network brings to its parent organization. Current employees and clients become the close-knit ties with whom the company interacts frequently. At the same time, former employees scattered across industries and sectors provide arm's-length ties that can relay important information and serve as important connections. "If I were running a company," Uzzi outlined, "I would want to maintain strong ties with some firms. But I would also like to have lots of looser ties that could be from my alumni network. Not necessarily people that I would want to approach and attempt to get new business from, but to use as more or less market research. So I could find out what's going on in their company, in their market—just kind of general information. I would want that mix of sources for market information."

Companies that engage or build alumni networks are still in the minority, but their numbers are on the rise. As the nature of work and the nature of management change, the way even former workers are managed is changing along with it. The benefits that companies have reaped from networks, as well as the research on the importance of a proper blend of network connections, definitely support the concept of keeping in touch with former employees. There is real value in celebrating departures and making sure that a farewell simply becomes a "see you later."

1 Comment