In 1998, I managed the server administration group for the new web team at the University of Minnesota. The U of M is a very large institution, with over 60,000 students across all system campuses. Until then, the university managed its student records on an aging mainframe system. But that was all about to change.

The mainframe was not Y2K compliant, so we were working to set up a new student records system delivered by PeopleSoft. The new system was a big deal to the university in many ways, not only for modernizing our records system but also for offering new features. Yet it lacked one key feature: You couldn't register for classes from your web browser.

That may seem like a major oversight by today's standards, but in the late 1990s, the World Wide Web was still pretty new. Amazon was only a few years old. eBay had just reached its first birthday. Google had recently gone live. Wikipedia didn't exist yet. In context, it's not that surprising that in 1998 PeopleSoft didn't support registering for courses via the web. But as a pioneering university that originated the Gopher network and created a functional web interface to the previous mainframe system, we believed web registration was a critical feature for the new student records system.

Our job on the web team was to build that missing web registration frontend to PeopleSoft.

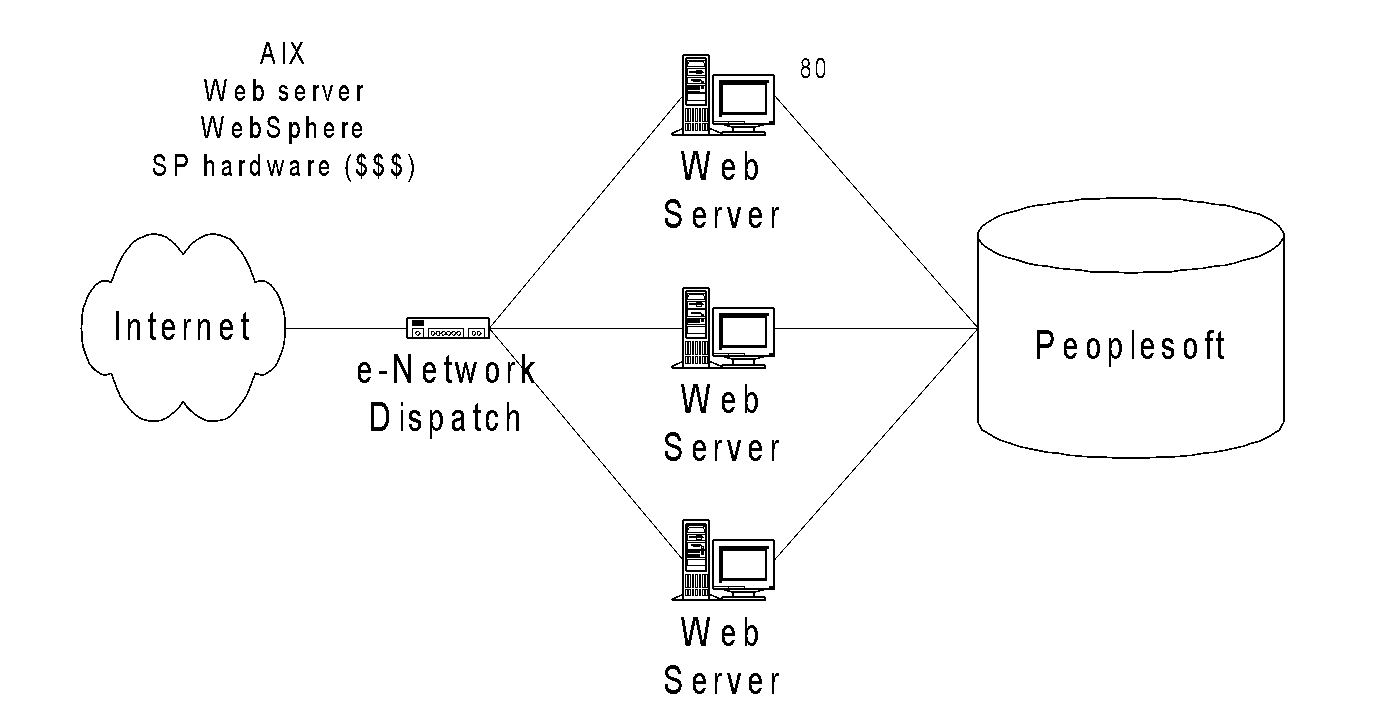

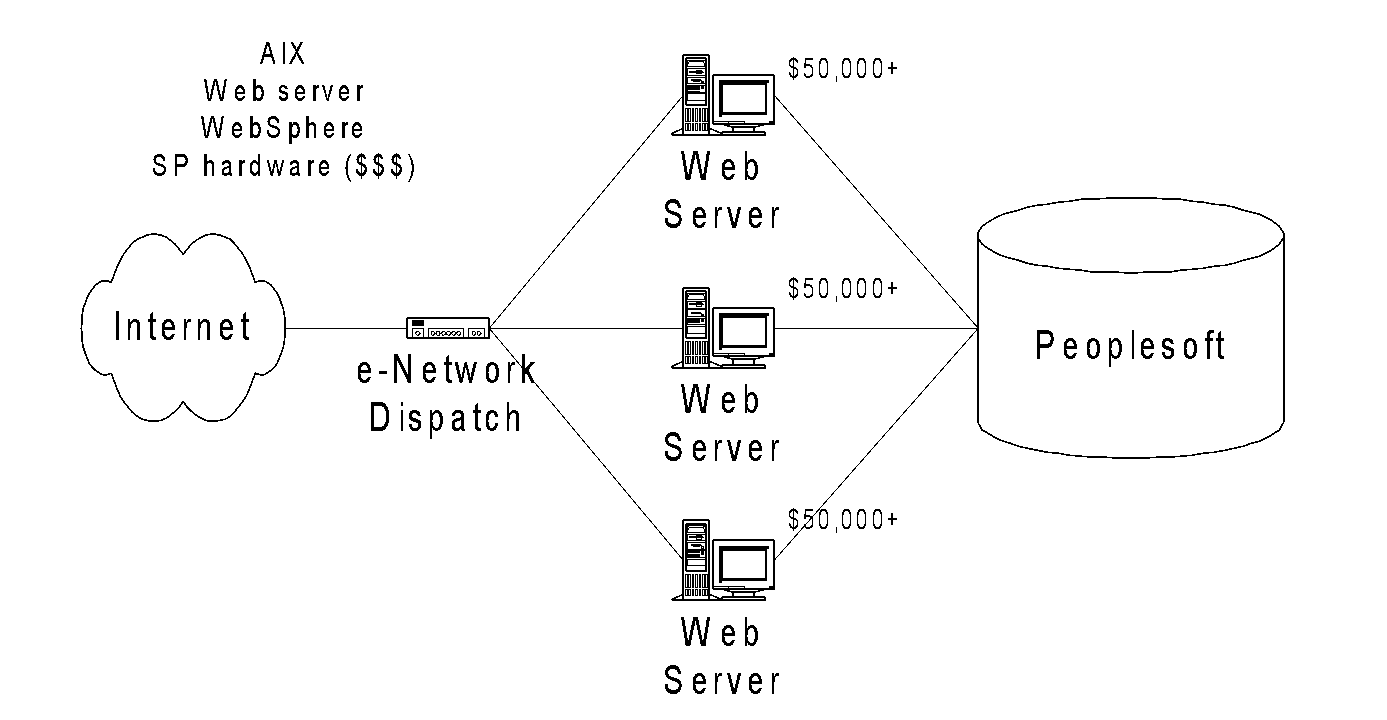

Fortunately, we didn't have to do it alone. We contracted with IBM, and over the next year, we worked together to build the new web registration system. IBM donated hardware and software to run the new web system: Three SP computer nodes running the latest versions of AIX, IBM Java, and IBM WebSphere, with a separate IBM load balancer dividing traffic between the three nodes.

After more than a year of development and testing, we finally went live! Unfortunately, it was an immediate failure.

Too much load

Throughout development, we were unable to realistically simulate the load of many students accessing the new system at once. But it was not from lack of trying. The university had a custom web load test software package, and IBM supplemented it with its own tool. But the web was still pretty new, and we didn't realize the web load testing tools just weren't up to the job yet.

After months of load testing with both tools, we had tuned the new web registration system for an expected load of 240 concurrent users.

Unfortunately, our actual usage was almost twice that. On day one, as soon as the system came online, over 400 students simultaneously signed into the new web registration system. Overwhelmed by the unexpected load, the three web servers crashed. We found ourselves constantly restarting the web servers as the high web traffic continued to crush them. As soon as we restarted one web server, the next would go down. And so on, for the entire month-long registration period.

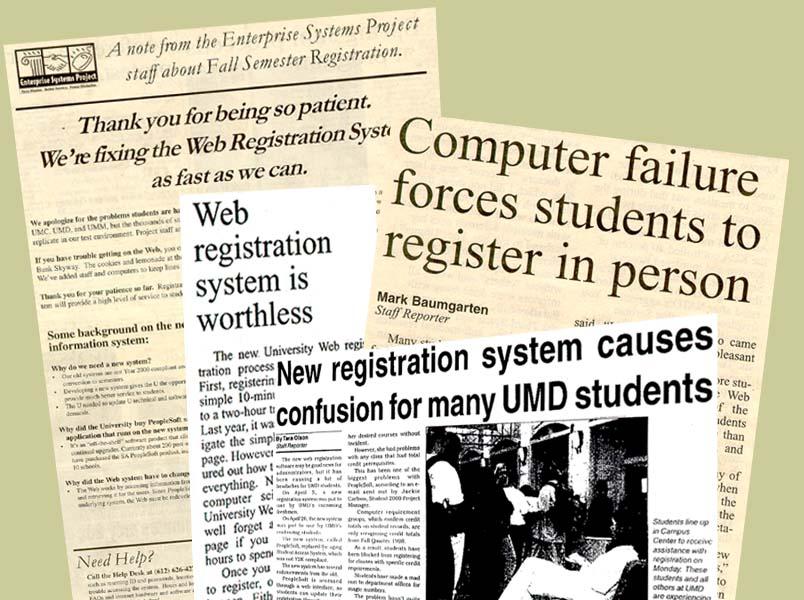

Without a reliable way to register for classes on the web, students had to sign up for classes the old-fashioned way: by going to the registrar's office. Lines to register went down the hallway and out the door. It wasn't long before the bad news hit the local news, with headlines such as "Computer failure forces students to register in person."

Having faced a very public defeat, we did our best to improve things for the next registration cycle, only six months away. We worked frantically to increase the capacity of the web system. Despite many code fixes and configuration tweaks, we were unable to boost the system to sufficiently support more users. Try as we might, we faced certain failure at the next registration cycle.

And as feared, the web system again failed dramatically at our next registration. The servers crashed again and again under the immense load. This time, the news headlines included such gems as: "Web registration system is worthless."

With another six months before our next go-live, we felt trapped. No one could figure out why the system was constantly crashing under load. We knew it would fail again at the next registration period. We had to do something, anything, to improve the system. But what to do? Every option was on the table.

What if we changed platforms?

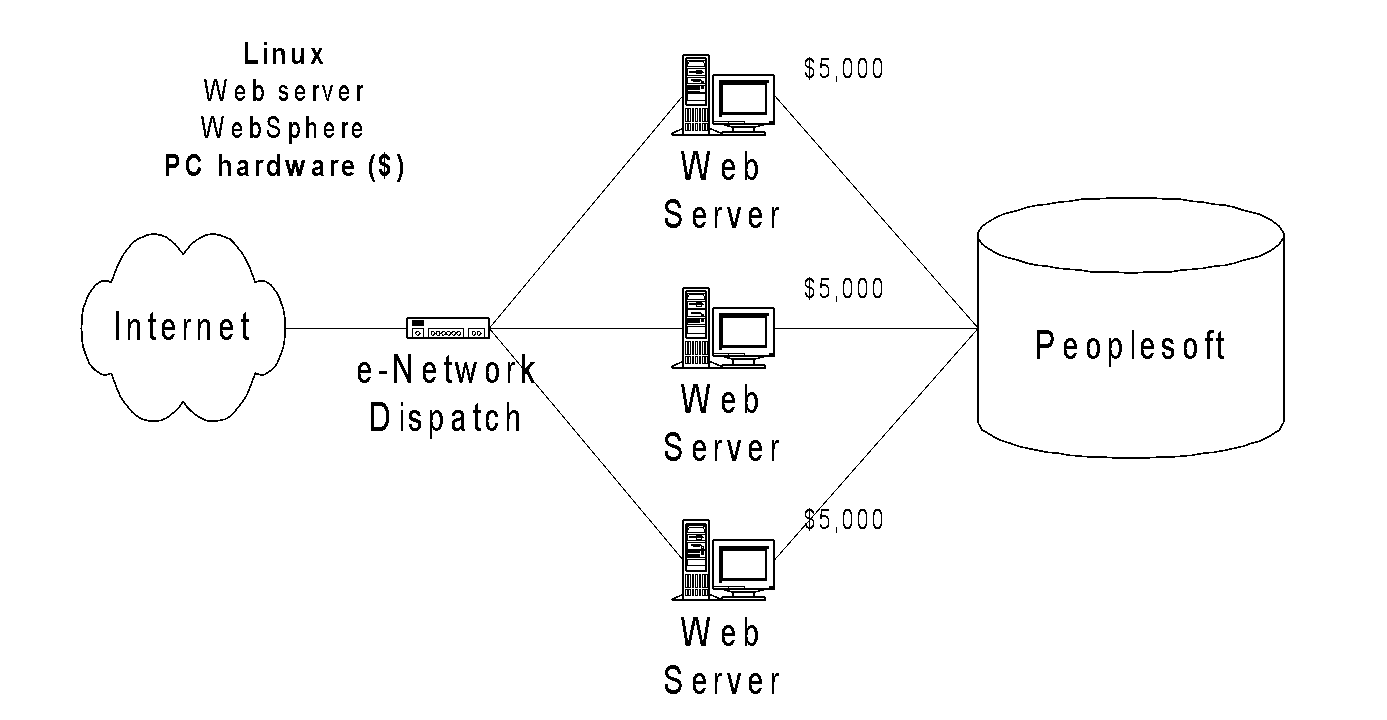

IBM had recently embraced Linux, releasing Linux versions of its Java and WebSphere products. All products were certified for RHEL (Red Hat Enterprise Linux), which several of us were already running on our desktop systems. We realized we now had the ecosystem to run the web registration system on Linux, as a supported platform. But would it perform any better on Linux than AIX?

After setting up a test server and running initial load tests, we were stunned to see one Linux server easily supporting what three AIX servers could not. A single Linux server running the same web registration code with the same IBM Java and IBM WebSphere sustained over 200 users.

We shared our findings with the registrar and the CIO, who approved our plan to migrate the web registration system to Linux. It was our first time running Linux in the University of Minnesota enterprise, but we had nothing to lose. The AIX system would fail again, anyway. Linux was a long shot, but it was our only hope.

We immediately ramped up new Linux servers for production. Colleagues in another team diverted several Intel servers to our effort, where we installed RHEL and the IBM components. We performed countless series of load tests on the new system, looking for weak points, only to find the Linux servers running smoothly.

After a restless two months, we finally went live. And it was a resounding success! The web registration system performed flawlessly on Linux, despite heavy usage. At our peak during that registration period, the Linux servers managed over 600 concurrent users, with barely a blip. Linux had rescued web registration at the University of Minnesota.

Lessons for success

As I look back on that massive rescue operation, I find several themes you can use to introduce Linux in your own organization:

- Solve a problem, don't stroke an ego.

When we proposed running Linux in the enterprise, we weren't doing it because we thought Linux was cool. Sure, we were Linux fans and we already ran Linux on the desktop and at home, but we were there to solve a problem. Our registrar and other stakeholders appreciated that Linux was a solution to a problem, not just something we wanted to do because Linux was cool.

- Change as little as possible.

Our success hinged on the fact that IBM had finally released versions of its Java and WebSphere products for Linux. This allowed us to minimize changes to the system as we migrated from AIX to Linux. Comparing the AIX configuration to the Linux configuration, only the hardware and operating system changed. Every other component on the system remained the same. It was this "known" quantity that instilled confidence in making the change.

- Be honest about the risks and benefits.

Our problem was obvious: Web registration had failed in our previous two registration cycles and would likely fail again. When we presented our idea to our stakeholders, proposing that we replace the AIX web servers with Linux, we were open about the expected risks and benefits. The bottom line was if we changed nothing, we would fail. If we tried Linux, we might fail or we might not. We shared our findings from our initial load tests, which demonstrated that Linux was more likely to succeed than fail.

But even if Linux failed, we could easily put the old AIX servers back into production. That "fallback" preparation reassured the registrar that we had appropriately measured the benefits and the risks and were prepared in case things went wrong.

- Communicate broadly.

In making our pitch to migrate to Linux, we cast a wide net. We wrote an executive white paper that clearly communicated what we planned to do and why we thought it would work. The key to this white paper's success was its brevity. Executives do not want to read a "novel" about a technical idea, nor do they want to get mired in the technical details. We intentionally wrote the white paper for the executive level, describing our proposal in broad strokes.

As we replaced the system with Linux, we provided regular updates to inform our stakeholders about our progress to build the new Linux system. After we finally went live on the Linux web registration system, we posted daily updates, reporting how many students had registered for classes on the new system, and if we saw any problems.

Even though it's been nearly two decades since our early failure with AIX and very successful experiment with Linux, all of these lessons still apply. Sure, Linux did the heavy lifting here, but our overall success was due to bringing people together in the spirit of solving a common problem. And that's a lesson that I think you can apply to pretty much any situation you face.

4 Comments