I think the first word I learned to type fast—and I mean really fast—was "fireball."

Like most of us, I started my typing career with a "hunt-and-peck" technique, using my index fingers and keeping my eyes focused on the keyboard to find letters as I needed them. It's not a technique that allows you to read and write at the same time; you might call it half-duplex. It was okay for typing cd and dir, but it wasn't nearly fast enough to get ahead in the game. Especially if that game was a MUD.

Gaming with multi-user dungeons

MUD is short for multi-user dungeon. Or multi-user domain, depending on who (and when) you ask. MUDs are text-based adventure games, like Colossal Cave Adventure and Zork, which you may have heard about in Season 2 Episode 1 of Command Line Heroes. But MUDs have an extra twist: you aren't the only person playing them. They allow you to group with others to tackle particularly nasty beasts, trade goods, and make new friends. They were the great granddaddies of modern massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) like Everquest and World of Warcraft. And, for an aspiring command-line hero, they offered an experience those modern games still don't.

My "home MUD" was NyxMud, which you could access by telnetting to port 2000 of nyx.cs.du.edu. It was the first command line I ever mastered. In a lot of ways, it allowed me to be a hero—or at least play the part of one.

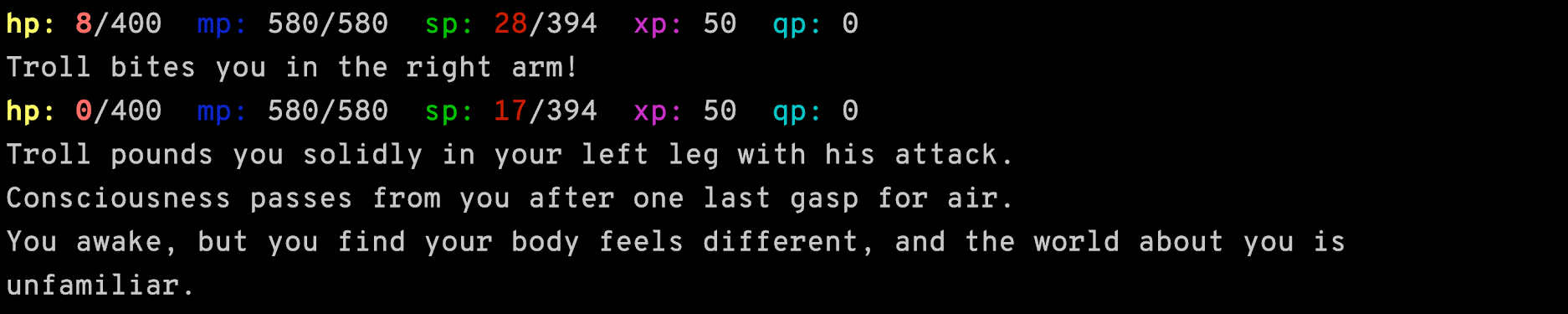

One special quality of NyxMud was that every time you connected to play, you started with an empty inventory. The gold you collected was still there from your last session, but none of your hard-won weapons, armor, or magical items were. So, at the end of every session, you had to make it back to a store to sell everything… and you would get a fraction of what you paid. If you were killed, the first player who encountered your lifeless body could take everything you had.

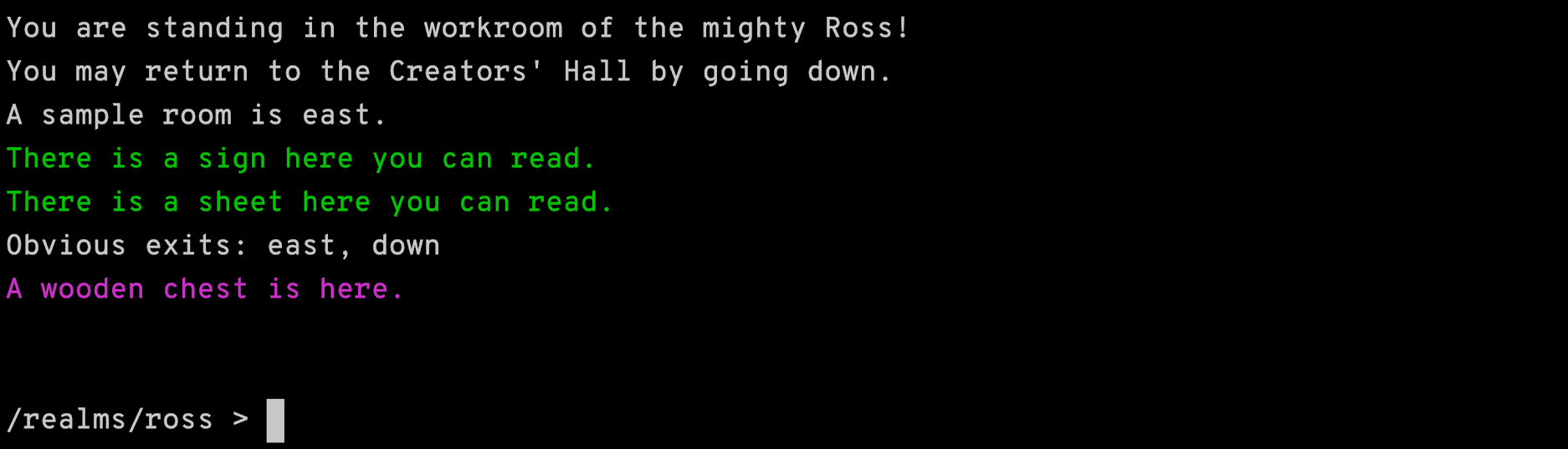

This shows a snippet of source code from a wizard's private workroom.

This made the game extremely sticky. Selling everything and quitting was a horrible thing to do, fiscally speaking. It meant that your session had to be profitable. If you didn't earn enough gold through looting and quests between the time you bought and sold your gear, you wouldn't be able to equip yourself as well the next time you played. If you died, it was even worse: You might find yourself killing balls of slime with a newbie sword as you scraped together enough gold for better gear.

I never wanted to "pay the store tax" by selling my gear, which meant a lot of late nights and sleeping through morning biology classes. Every modern game designer wants you to say, "I can't have dinner now, Dad, I have to keep playing or I'm in big trouble." NyxMud had me so hooked that I was saying that several decades ago.

So when it came time to "cast fireball" or die an imminent and ruinous death, I was forced to learn how to type properly. It also forced me to take a social approach to the game—having friends around to fight off scavengers allowed me to reclaim my gear when I died.

Command-line heroes all have some things in common: They work with others and they type wicked fast. NyxMud trained me to do both.

From gamer to creator

NyxMud was not the largest MUD by any measure. But it was still an expansive world filled with hundreds of areas and dozens of epic adventures, each one tailored to a different level of a player's advancement. Over time, it became apparent that not all these areas were created by the same person. The term "user-generated content" was yet to be invented, but the concept was dead simple even to my young mind: This entire world was created by a group of people, other players.

Once you completed each of the challenging quests and achieved level 20, you became a wizard. This was a singularity of sorts, beyond which existed a reality known only to a few. During lunch breaks at school, my circle of friends would muse about the powers of a wizard; you see, we knew wizards could create rooms, beasts, items, and quests. We knew they could kill players at will. We really didn't know much else about their powers. The whole thing was shrouded in mystery.

In our group of high school friends, Eddie was the first to become a wizard. His flaunting and taunting threw us into overdrive, and Jared was quick to follow. I was last, but only by a day or two. Now that 25 years have passed, let's just call it a three-way tie. We discovered it was pretty much what we thought. We could create rooms, beasts, items, and quests. We could kill players. Oh, and we could become invisible. In NyxMud, that was just about it.

This shows a wizard’s private workroom.

Wizards used the Wand of Creation, an item invented by Quasi (rhymed with "crazy"), the grand wizard. He alone had access to the code for the engine, due to a strict policy set by the administrator of the Nyx system where it ran. So, he created a complicated, magical object that would allow users to generate new game elements. This wand, when invoked, ran the wizard through a menu-based workflow for creating rooms and objects, establishing quest objectives, and designing terrible monsters.

Having that magical wand was enough. I immediately set to work creating new lands and grand adventures across a series of islands, each with a different, exotic climate and theme. I found immense pleasure in hovering, invisible, as the savage beasts from my imagination would slay intrepid adventurers over and over again. But it was even better to see players persevere after a hard battle, knowing I had tweaked and tuned my quests to be just within the realm of possibility.

Being accepted into this elite group of creators was one of the more rewarding and satisfying moments of my young life. Each new wizard would have to pass my test, spending countless hours and sleepless nights, just as I did, to complete the quests of the wizards before me. I had proven my value through dedication and contribution. It was just a game, but it was also a community—the first one I encountered, and the one that showed me how powerful a properly run meritocracy could be.

From creator to coder

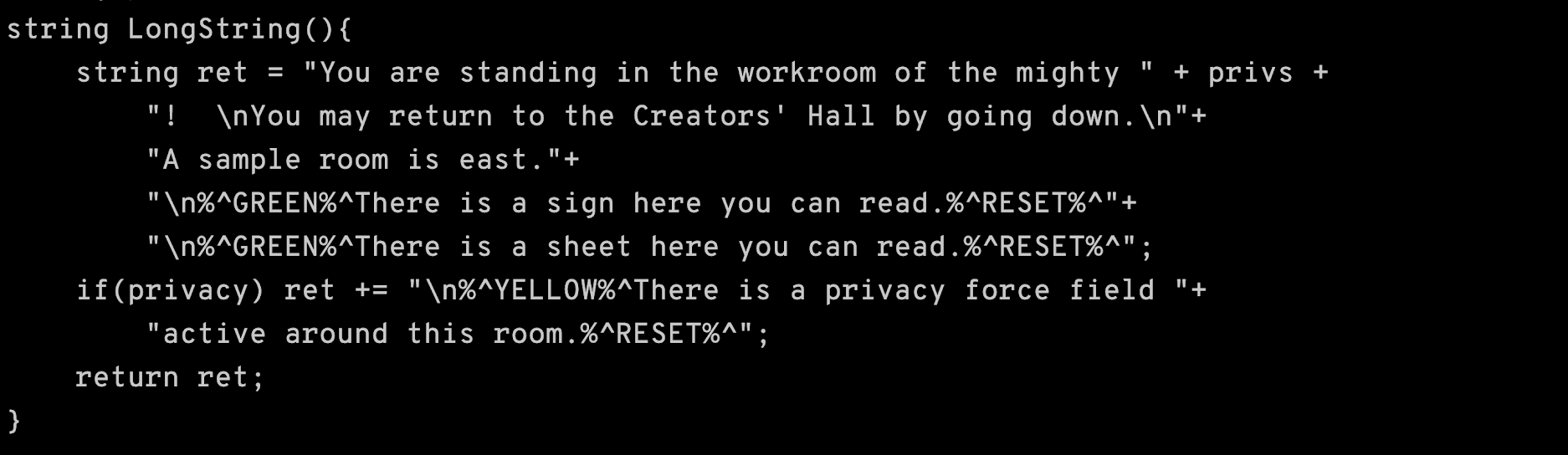

NyxMud was based on the LPMud codebase, which was created by Lars Pensjö. LPMud was not the first MUD software developed, but it contained one very important innovation: It allowed players to code the game from within the game. It accomplished this by separating the mudlib, which contained all the content and user-facing functionality, from the driver, which acted as a real-time interpreter for the mudlib and provided access to basic network and storage resources. This architecture meant the mudlib could be edited on-the-fly by virtually untrusted people (e.g., players like me) who could augment the game experience without being able to do anything particularly harmful to the server it was running on. The driver provided an "air gap."

This air gap was not enough for NyxMud; it was allowed to exist only if a single person could be trusted to write all the code. In most LPMud systems, players who became wizards could use ls, cd, and ed to traverse the mudlib and modify files, all from the same command line they had used countless times for casting fireballs and drinking potions. Quasi went to great lengths to modify the Nyx mudlib so wizards couldn't traipse around the system with a full set of sharp tools. The Wand of Creation was born.

As a wizard who hadn't played any other MUDs, I didn't miss what I never had. Besides, I didn't have a way to access any systems at the time—telnet was disabled on Nyx, which was my only connection to the internet. But I did have access to Usenet, which provided me with The Totally Unofficial List of Internet Muds. It was clear there was more of the MUD universe for me to discover. I read all the documentation about mudlibs I could get my hands on and got some exposure to LPC, the niche programming language used to create new content.

I convinced my dad to make an investment in my future by paying for a shell account at Netcom (remember that?). With that account, I could connect to any MUD I wanted, and, based on several strong recommendations, I chose Viking MUD. It still exists today. It was a real MUD, the bleeding edge, and it showcased the true potential of a universe built with code instead of the limited menu system of a magical wand. But, to be honest, I never got very far as a player. I really wanted to learn how to code, and I didn't want to slay slimeballs with a noobsword for hours to get there.

There was a very small window of time—between February and August 1992, according to Lauren P. Burka's Mud Timeline—where the perfect place existed for my exploration. The Mud Institute (TMI for short) was a very special MUD designed to teach people how to program in LPC, illuminating the darkest corners of the mudlib. It offered immediate omnipotence to all who applied and built a community for the development of a new generation of LPMuds.

This was my first exposure to C programming, as LPC was essentially a flavor of C that shared the same types, control structures, and syntax. It was C with training wheels, designed for rapid creation of content but allowing coders to develop intricate game scenarios (if they had the chops). I had always seen the curly brace on my keyboard, and now I knew what it was used for. The only thing I can remember creating was a special vending machine, somewhat inspired by the Wand of Creation, that would create the monster of your choice on-the-spot.

TMI was not a long-lasting phenomenon; in fact, it was gone almost before I had a chance to discover it. It quickly abandoned its educational charter, although its efforts were ultimately productive with the release of MudOS—which still lives through its modern-day descendant, FluffOS. But what a treasure trove of knowledge about a highly specific subject! Immediately after logging in, I was presented with a complete set of developer tools, a library of instructional materials, and a ton of interesting sample code to learn from.

I never talked to anyone or asked for any help, and I never had to. The community had published just enough resources for me to get started by myself. I was able to learn the basics of structured programming without a textbook or teacher, all within the context of a fantastical computer game. As a result, I have had a long and (mostly) fulfilling career in technology.

The line from Field of Dreams, "if you build it, they will come," is almost certainly untrue for communities. The folks at The Mud Institute built the makings of a great community, but I can't say they were successful. They didn't become a widely known wizarding school—in fact, it's really hard to find any information about TMI at all. If you build it, they may not come; if they do, you may still fail. But it still accomplished something wonderful that its creators never thought to predict: It got me excited about programming.

For more on the gamer-to-coder phenomenon and its effect on open source community culture, check out Episode 1 of Season 2 of Command Line Heroes.

4 Comments