I recently wrote about how I find Jupyter projects, especially JupyterLab, to be a magical Python development experience. In researching how the various projects are related to each other, I recapped how Jupyter began as a fork from IPython. As Project Jupyter's The Big Split™ announcement explained:

"If anyone has been confused by what Jupyter is[1], it's the exact same code that lived in IPython, developed by the same people, just in a new home under a new name."

That [1] links to a footnote that further clarifies:

"I saw 'Jupyter is like IPython, but language agnostic' immediately after the announcement, which is a great illustration of why the project needs to not have Python in the name anymore, since it was already language agnostic at the time."

The fact that Jupyter Notebook and IPython forked from the same source code made sense to me, but I got lost in the current state of the IPython project. Was it no longer needed after The Big Split™ or is it living on in a different way?

I was surprised to learn that IPython's significance continues to add value to Pythonistas, and that it is an essential part of the Jupyter experience. Here's a portion of the Jupyter FAQ:

Are any languages pre-installed?

Yes, installing the Jupyter Notebook will also install the IPython kernel. This allows working on notebooks using the Python programming language.

I now understand that writing Python in JupyterLab (and Jupyter Notebook) relies on the continued development of IPython as its kernel. Not only that, IPython is the powerhouse default kernel, and it can act as a communication bus for other language kernels according to the documentation, saving a lot of time and development effort.

The question remains, what can I do with just IPython?

What IPython does today

IPython provides both a powerful, interactive Python shell and a Jupyter kernel. After installing it, I can run ipython from any command line on its own and use it as a (much prettier than the default) Python shell:

$ ipython

Python 3.7.3 (default, Mar 27 2019, 09:23:15)

Type 'copyright', 'credits' or 'license' for more information

IPython 7.4.0 -- An enhanced Interactive Python. Type '?' for help.

In [1]: import numpy as np

In [2]: example = np.array([5, 20, 3, 4, 0, 2, 12])

In [3]: average = np.average(example)

In [4]: print(average)

6.571428571428571That brings us to the more significant issue: IPython's functionality gives JupyterLab the ability to execute the code in every project, and it also provides support for a whole bunch of functionality that's playfully called magic (thank you, Nicholas Reith, for mentioning this in a comment on my previous article).

Getting magical, thanks to IPython

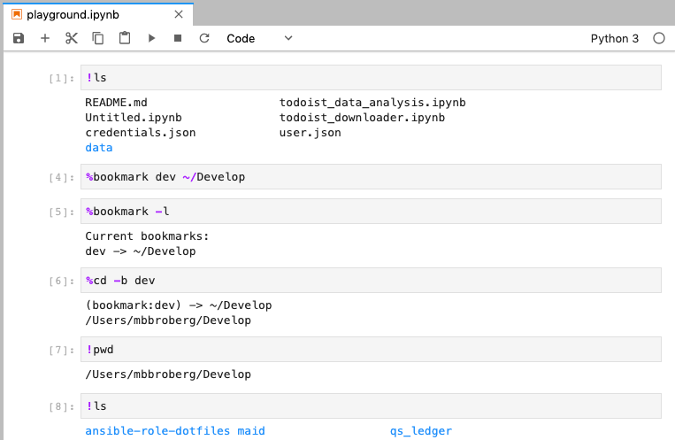

JupyterLab and other frontends using the IPython kernel can feel like your favorite IDE or terminal emulator environment. I'm a huge fan of how dotfiles give me the power to use shortcuts, and magic has some dotfile-like behavior as well. For example, check out %bookmark. I've mapped my default development folder, ~/Develop, to a shortcut I can run at any time and hop right into it.

The use of %bookmark and %cd, alongside the ! operator (which I introduced in the previous article), are powered by IPython. As the documentation states:

To Jupyter users: Magics are specific to and provided by the IPython kernel. Whether Magics are available on a kernel is a decision that is made by the kernel developer on a per-kernel basis.

Wrapping up

I, as a curious novice, was not quite sure if IPython remained relevant to the Jupyter ecosystem. I now have a new appreciation for the continuing development of IPython now that I realize it's the source of JupyterLab's powerful user experience. It's also a collection of talented contributors who are part of cutting edge research, so be sure to site them if you use Jupyter projects in your academic papers. They make it easy with this ready-made citation entry.

Be sure to keep it in mind when you're thinking about open source projects to contribute to, and check out the latest release notes for a full list of magical features.

1 Comment