In the first part of this series, I illustrated what an Open Organization chart looks like based on the book Team of Teams, by Stanley McChrystal. In this second and final part, I explore concerns about the information flow using this chart and give some examples of how it might work and (possibly unknowingly) has worked in the past.

Building team-to-team adaptability, collaboration, and transparency

Sometimes activities fit exactly with a single specialty and group responsibility. Other times these responsibilities overlap, with one party having primary responsibility and another playing a more minor but important, supportive role. Both must know each other's actions to be successful.

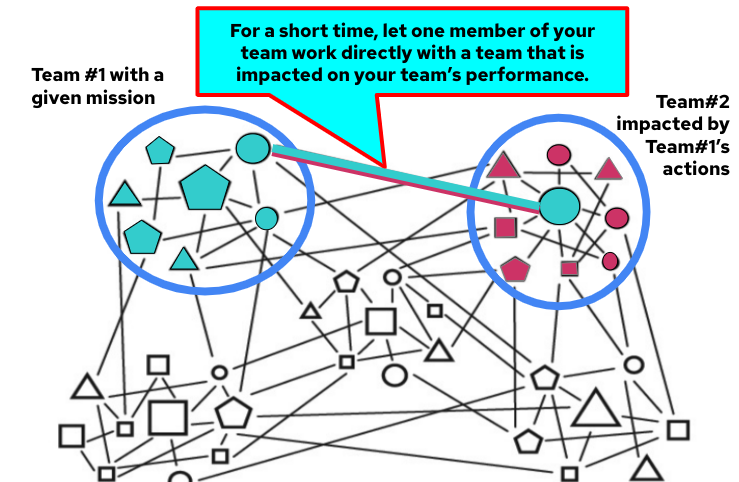

(Taken from Team of Teams, page 129 and modified by Ron McFarland)

Efficient communication does not go up a vertical line to top management. Instead, many connections are crisscrossing through related teams with a lot of confirming overlap. These communication paths are only between groups that impact each other. This redundant overlapping may retard efficiency but result in improved adaptability. It is adept at responding instantly and creatively to unexpected events.

First, create oneness within each team.

Second, a team should establish communication with other teams impacted by its performance. Notice the light blue members sitting in another team. They are learning that team's environment on the one hand and representing their own team on the other. They are building a bridge between teams.

Finally, all teams should have cohesiveness within the entire organization. If there is great transparency and collaboration between them, far more activities will be conducted concurrently instead of sequentially, speeding up execution. Also, real-time transparency will allow rapid adaptability in any situation. As teams increase, their connections should increase exponentially to maintain rapid collaboration, adaptability, and transparency.

Each one of those teams has a direct, specific purpose. The link to other teams means that their performance and results will impact other groups. Knowing another team's working environment and how well they are doing helps them complete their assignments better.

This horizontal communication link is faster than going up a vertical organization chart. These interactions are vital in an age where speed and adaptability are critical.

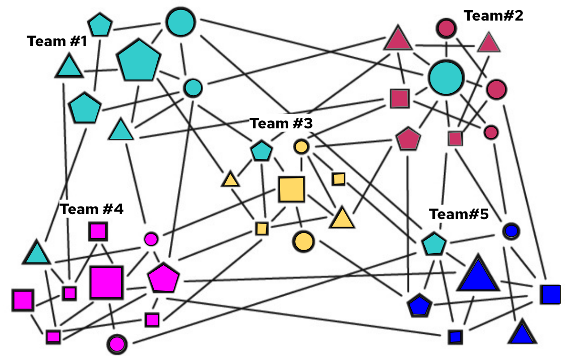

According to McChrystal, you can't make one extra large team to create overall organizational adaptability. You must create high-functioning smaller teams where everyone knows what others are doing. This approach can be easily implemented in a group of up to about 25 members. Up to 50 members may be barely doable, but it's doubtful for 100 members and impossible in an organization with thousands of members. Therefore, you must create many low-head-count teams.

Where is the leadership?

Leadership is moving all the time, depending on the challenge and goals of each team. I wrote about this in my article, "What is adaptive leadership?" In any situation, the team considers who they will follow. More than likely, a person on the frontline who is the most experienced and qualified to guide the other team members will become the leader that people will follow. I think this is true in the teams that McChrystal is talking about.

The environment of accelerating speed, swelling complexity, and interdependence has forced organizations to be more adaptable, more collaborative, and more transparent than in the past. Therefore, a frontline respected team member must be a hands-on leader.

Team representation on other teams

Knowing how your team impacts other teams and giving other teams the ability to sense your team's situation will determine success or failure when agile adaptability is required. This is a critical point to improve collaboration and coordination between all team's activities.

(Taken from Team of Teams, page 129 and modified by Ron McFarland)

You don't need to have everyone know every member of the other teams in the organization. You only need one quality team member (a representative) to know all the other related teams. That one representative can present and speak for other team members on how their work impacts other teams. In the organization chart above, imagine temporarily having one of the light blue team members on another team.

This representative should not be adopted as a full-functioning new member, though. They are not leaving one team for another but just serving as a supportive observer.

When selecting a representative from your team to observe and work with another team, choose someone with effective communication skills to speak for your team. Remember, the other team members may be very different from your own. An example of this is an analyst and a frontline soldier. A representative must be able to be accepted by them, which might require doing manual support tasks for a time. McChrystal calls those that take these assignments "Liaison Officers (LNOs)." He calls the projects "embedding and liaison programs." An LNO doesn't need to have any of the skills needed in the other group but must have the ability to understand their situation. Also, when an LNO returns to your team, that person should report on how your team's work impacts the other team. McChrystal suggests this can solve the problem of "out of sight, out of mind" by making the situation of those other teams come alive.

Furthermore, it might be helpful to create common areas where members from different teams can casually gather and share information. You may also lay out the physical facility so members often walk by other groups and get a glimpse at what they're up to. Possibly even a casual discussion could develop. It could maximize the cross-pollination of ideas. Teams could even have a visual activity board, so members of other groups could see at a glance what one another is up to.

To encourage collaboration, McChrystal established an "Operation and intelligence briefing" that happened six days a week (and was never canceled). He invested in mobile teleconferencing equipment and a briefing room. At least one member of each team had to participate in each meeting. The more, the better.

Members had to sit with other groups to understand better what was happening in different teams and watch them work. Getting briefings is good but not as useful as observing the skills of another unit in action.

This idea reminds me of my days just out of graduate school in Japan, entering my first large Japanese company. It was company policy for university graduates to work in two or three related departments before settling into a specialty in one department. This approach gave me a feeling for other departments' activities. To get things done, the kacho (section chief) was the real achiever, the critical team representative. On the organization chart, the kacho communicated with other kachos at their horizontal level. Communicating with superiors was often a waste of time.

From small teams to large organizations

To scale adaptability, collaboration, transparency, and community purpose across an organization, you have to link and connect teams with the other teams they impact. One team can anticipate what others are doing and better prepare themselves if assignments come to their team. By knowing the overall situation, one can anticipate concerns before they become major problems. McChrystal presents a massive organization like NASA. NASA employees initially complained about the added level of collaboration and information-sharing transparency, as it was extra work. But, after seeing the value of their efforts, the complaints stopped.

In addition to the complaints about extra work, competition issues might also arise. There could be environments where teams compete against each other. There are times when competition is very productive and motivating. In other cases, it's disruptive and counter-productive. I wrote about this in my articles "What determines how collaborative you'll be?" and "To compete or to collaborate? 4 criteria for making the call." In most organizations working in extremely volatile, interdependent situations with many unknowns, team-to-team cooperation is far more productive. Every team member has to know where they stand and how they impact all branches of the organization. You must convince members that it is their responsibility to know and support other teams.

Considering overall community purpose, these representatives can share where team goals reside within the overall organizational goals. This approach broadens overall community purpose and can be more helpful to other teams. A team could be extremely productive but counter-productive to other groups without continual communication. With today's technology, this real-time communication is effortlessly possible.

This is not to say that each person and team will become a generalist in many skills. They maintain their expertise but know what others are doing within their specialties.

Team-to-team, stakeholder-to-stakeholder

Teams not only communicate and collaborate with each other within their organization, but they also communicate and collaborate well with outside stakeholders that are dependent on their activities. I gave a presentation on stakeholders, which stresses a company's surroundings.

Shared understanding, empowered decision-making, and rapid execution create adaptability. That adaptability can successfully address unpredictability. Outside stakeholders impacted by teams must play a role in that success. They are part of the community.

Automotive industry adaptation example

It is not easy for an organization to stop doing what was successful in the past and start doing something completely new, but sometimes adapting is required. Automotive dealers with service departments and parts departments have to carry auto parts. When market demand falls, these departments must stop stocking low-demand automotive parts. Also, the parts maker that supplies the dealer has to stop producing and stocking them. To be adaptive, service departments can help keep older vehicles in operation by developing parts modification systems that can convert a specialty item into a universal component to be installed in a wide variety of older vehicle models. It is more expensive than volume production but far cheaper than stocking products with no demand. Just like modifying parts, management sometimes has to be modified with a changing working environment.

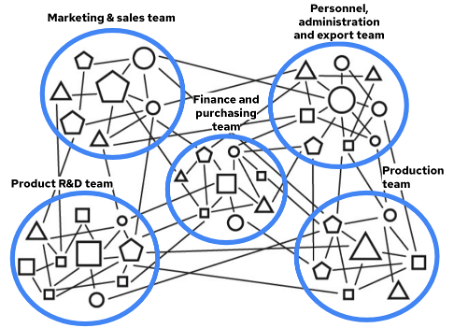

Joint production in China, a personal case study

I worked on a project to rent a building in China to an American company so that it could manufacture in China and export worldwide. It was such a small company that it couldn't just start manufacturing independently. Also, it had no expertise in working with the Chinese government. So we created a division in my Japanese company to handle the operation.

Consider my Japanese company as one team and that American company as another team. Our lawyer told me that to make this project work, responsibility should be very carefully negotiated and decided on. I created a Major responsibility/minor responsibility table. Once completed, I had both presidents sign it as part of the agreement. As these parties had to act like one company, I did not want one party to be totally responsible for an activity and the other party not responsible at all.

To make things more complicated, there were Japanese employees in Japan, with Chinese employees in China working for the Japanese company, and American employees in the USA, with Chinese employees in China working indirectly for the American company. I had to bring them all together to work jointly.

(Taken from Team of Teams, page 129 and modified by Ron McFarland)

Study the organization chart above and consider the following points:

- The American company in the USA handled all marketing and sales.

- The staff in China did all the Chinese personnel activities, including hiring and training.

- The American company handled all of the product development and production process development.

- The staff in China made all equipment and production raw materials purchases, but it was strictly on behalf of the American company.

- The Chinese operation supervised all production in China.

- The Japanese company controlled all the facilities in China.

- The staff in Japan and the USA coordinated all of the billing and financing.

- The leaders were the heads of each team in each process.

- The financing was initially handled by the Chinese company and then invoiced to the American company.

This collaboration was a total success for all parties. The Japanese company received money for space rental, a commission on employee dispatch, a commission on material purchases, and a general administration fee for export processing and other activities. The American company was profitable on their products exported worldwide. The Chinese company maintained profitable operations. That project went on for eight years, and the Chinese government didn't even know the American company existed, as all their activities fell within a division of my Japanese company. After that, the American company confidently set up its own independent production facility in China.

Team of Teams: Stronger together than each of its parts

A team of teams organization leads to a system of trust that serves the common good. This structure is best suited to meet this rapidly changing world by being more adaptive. There are requirements, though:

- Radical sharing of information (transparency).

- Extreme decentralization of decision-making authority and execution.

- Mutual bonds of trust and communication with other groups and teams.

- Interconnected communication system that can service the entire community that creates a shared consciousness. Knowing other people in other teams (functions and responsibilities) and establishing multiple paths to get things done makes teams more adaptive in crises. A single best path is too fragile.

- A community built on associations that both contribute to and benefit from their efforts directly or indirectly.

Wrap up

I've presented you with an image of a new organizational chart. Unofficially, to get things done, horizontal communication has been going on for decades. The difference is that updates happen within minutes, not just at weekly or monthly meetings.

Comments are closed.