In the first of this series on Docker security, I wrote "containers do not contain." In this second article, I'll cover why and what we're doing about it.

Docker, Red Hat, and the open source community are working together to make Docker more secure. When I look at security containers, I am looking to protect the host from the processes within the container, and I'm also looking to protect containers from each other. With Docker we are using the layered security approach, which is "the practice of combining multiple mitigating security controls to protect resources and data."

Basically, we want to put in as many security barriers as possible to prevent a break out. If a privileged process can break out of one containment mechanism, we want to block them with the next. With Docker, we want to take advantage of as many security mechanisms of Linux as possible.

Luckily, with Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) 7, we get a plethora of security features.

File System Protections

Read-only mount points

Some Linux kernel file systems have to be mounted in a container environment or processes would fail to run. Fortunately, most of these filesystems can be mounted as "read-only". Most apps should never need to write to these file systems.

Docker mounts these file systems into the container as "read-only" mount points.

. /sys

. /proc/sys

. /proc/sysrq-trigger

. /proc/irq

. /proc/bus

By mounting these file systems as read-only, privileged container processes cannot write to them. They cannot effect the host system. Of course, we also block the ability of the privileged container processes from remounting the file systems as read/write. We block the ability to mount any file systems at all within the container. I will explain how we block mounts when we get to capabilities.

Copy-on-write file systems

Docker uses copy-on-write file systems. This means containers can use the same file system image as the base for the container. When a container writes content to the image, it gets written to a container specific file system. This prevents one container from seeing the changes of another container even if they wrote to the same file system image. Just as important, one container can not change the image content to effect the processes in another container.

Capabilities

Linux capabilities are explained well on their main page:

For the purpose of performing permission checks, traditional UNIX implementations distinguish two categories of processes: privileged processes (whose effective user ID is 0, referred to as superuser or root), and unprivileged processes (whose effective UID is nonzero). Privileged processes bypass all kernel permission checks, while unprivileged processes are subject to full permission checking based on the process's credentials (usually: effective UID, effective GID, and supplementary group list). Starting with kernel 2.2, Linux divides the privileges traditionally associated with superuser into distinct units, known as capabilities, which can be independently enabled and disabled. Capabilities are a per-thread attribute.

Removing capabilities can cause applications to break, which means we have a balancing act in Docker between functionality, usability and security. Here is the current list of capabilities that Docker uses: chown, dac_override, fowner, kill, setgid, setuid, setpcap, net_bind_service, net_raw, sys_chroot, mknod, setfcap, and audit_write.

It is continuously argued back and forth which capabilities should be allowed or denied by default. Docker allows customers to manipulate default list with the command line options for Docker run.

Capabilities removed

Docker removes several of these capabilities including the following:

| CAP_SETPCAP | Modify process capabilities |

| CAP_SYS_MODULE | Insert/Remove kernel modules |

| CAP_SYS_RAWIO | Modify Kernel Memory |

| CAP_SYS_PACCT | Configure process accounting |

| CAP_SYS_NICE | Modify Priority of processes |

| CAP_SYS_RESOURCE | Override Resource Limits |

| CAP_SYS_TIME | Modify the system clock |

| CAP_SYS_TTY_CONFIG | Configure tty devices |

| CAP_AUDIT_WRITE | Write the audit log |

| CAP_AUDIT_CONTROL | Configure Audit Subsystem |

| CAP_MAC_OVERRIDE | Ignore Kernel MAC Policy |

| CAP_MAC_ADMIN | Configure MAC Configuration |

| CAP_SYSLOG | Modify Kernel printk behavior |

| CAP_NET_ADMIN | Configure the network |

| CAP_SYS_ADMIN | Catch all |

Lets look closer at the last couple in the table. By removing CAP_NET_ADMIN for a container, the container processes cannot modify the systems network, meaning assigning IP addresses to network devices, setting up routing rules, modifying iptables.

All networking is setup by the Docker daemon before the container starts. You can manage the containers network interface from outside the container but not inside.

CAP_SYS_ADMIN is special capability. I believe it is the kernel catchall capability. When kernel engineers design new features into the kernel, they are supposed to pick the capability that best matches what the feature allows. Or, they were supposed to create a new capability. Problem is, there were originally only 32 capability slots available. When in doubt the kernel engineer would just fall back to using CAP_SYS_ADMIN. Here is the list of things CAP_SYS_ADMIN allows according to /usr/include/linux/capability.

| Allow configuration of the secure attention key | Allow administration of the random device |

| Allow examination and configuration of disk quotas | Allow setting the domainname |

| Allow setting the hostname | Allow calling bdflush() |

| Allow mount() and umount(), setting up new smb connection | Allow some autofs root ioctls |

| Allow nfsservctl | Allow VM86_REQUEST_IRQ |

| Allow to read/write pci config on alpha | Allow irix_prctl on mips (setstacksize) |

| Allow flushing all cache on m68k (sys_cacheflush) | Allow removing semaphores |

| Used instead of CAP_CHOWN to "chown" IPC message queues, semaphores and shared memory | Allow locking/unlocking of shared memory segment |

| Allow turning swap on/off | Allow forged pids on socket credentials passing |

| Allow setting readahead and flushing buffers on block devices | Allow setting geometry in floppy driver |

| Allow turning DMA on/off in xd driver | Allow administration of md devices (mostly the above, but some extra ioctls) |

| Allow access to the nvram device | Allow administration of apm_bios, serial and bttv (TV) device |

| Allow manufacturer commands in isdn CAPI support driver | Allow reading non-standardized portions of pci configuration space |

| Allow DDI debug ioctl on sbpcd driver | Allow setting up serial ports |

| Allow sending raw qic-117 commands | Allow enabling/disabling tagged queuing on SCSI controllers and sending arbitrary SCSI commands |

| Allow setting encryption key on loopback filesystem | Allow setting zone reclaim policy |

| Allow tuning the ide driver |

The two most important features that removing CAP_SYS_ADMIN from containers does is stops processes from executing the mount syscall or modifying namespaces. You don't want to allow your container processes to mount random file systems or to remount the read-only file systems.

--cap-add --cap-drop

Docker run also has a feature where you can adjust the capabilities that your container requires. This means you can remove capabilities your container does not need. For example, if your container does not need setuid and setgid you can remove this access by executing:

docker run --cap-drop setuid --cap-drop setgid -ti rhel7 /bin/sh

You can even remove all capabilities or add them all:

docker run --cap-add all --cap-drop sys-admin -ti rhel7 /bin/sh

This command would add all capabilities except sys-admin.

Namespaces

Some of the namespaces that Docker sets up for processes to run in also provide some security.

PID namespace

The PID namespace hides all processes that are running on a system except those that are running in your current container. If you can't see the other processes, it makes it harder to attack the process. You can't easily strace or ptrace them. And, killing the pid 1 of a process namespace will automatically kill all of the processes within a container, which means an admin can easily stop a container.

Network namespace

The network namespace can be used to implement security. The admin can setup the network of a container with routing rules and iptables such that the processes within the container can only use certain networks. I can imagine people setting up three filtering containers:

- One only allowed to communicate on the public Internet.

- One only allowed to communicate on the private Intranet.

- One connected to the other two containers, relaying messages back and forth between between the containers, but blocking inappropriate content.

cgroups

One type of attack on a system could be described as a Denial Of Service. This is where a process or group of processes use all of the resources on a system, preventing other processes from executing. cgroups can be used to mitigate this by controlling the amount of resources any Docker container can use. For example the CPU cgroup can be setup such that an administrator can still login to a system where a Docker container is trying to dominate the CPU and kill it. New cgroups are being worked on to help control processes from using too many resources like open files or number of processes. Docker will take advantage of these cgroups as they become available.

Device cgroups

Docker takes advantage of the special cgroups that allows you to specify which device nodes can be used within the container. It blocks the processes from creating and using device nodes that could be used to attack the host.

Device nodes allow processes to change the configuration of the kernel. Controlling which devices nodes are available controlls what a process is able to do on the host system.

The following device nodes are created in the container by default.

/dev/console,/dev/null,/dev/zero,/dev/full,/dev/tty*,/dev/urandom,/dev/random,/dev/fuse

The Docker images are also mounted with nodev, which means that even if a device node was pre-created in the image, it could not be used by processes within the container to talk to the kernel.

Note: The creation of device nodes could also be blocked by removing the CAP_MKNOD capability. Docker has chosen to not do this, in order to allow processes to create a limited set of device nodes. In the futures section, I will mention the --opt command line option, which I would like to use to remove this capability.

AppArmor

Apparmor is available for Docker containers on systems that support it. But I use RHEL and Fedora, which do not support AppArmor, so you will have to investigate this security mechanism elsewhere. (Besides, I use SELinux as you well know.)

SELinux

First, a little about SELinux:

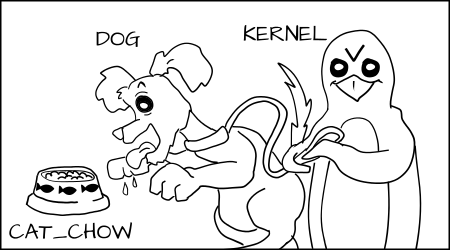

- SELinux is a LABELING system

- Every process has a LABEL

- Every file, directory, and system object has a LABEL

- Policy rules control access between labeled processes and labeled objects

- The kernel enforces the rules

SELinux implements a Mandatory Access Control system. This means the owners of an object have no control or discretion over the access to an object. The kernel enforces Mandatory Access Controls. I have described how SELinux enforcement works in the visual guide to SELinux policy enforcement (and subsequent, SELinux Coloring Book).

I will use some of the cartoons from that article to describe how we use SELinux to control the access allowed to Docker container processes. We use two type of SELinux enforcement for Docker containers.

Type enforcement

Type Enforcement protects the host from the processes within the container

The default type we use for running Docker containers is svirt_lxc_net_t. All container processes run with this type.

All content within the container is labeled with the svirt_sandbox_file_t type.

svirt_lxc_net_t is allowed to manage any content labeled with svirt_sandbox_file_t.

svirt_lxc_net_t is also able to read/execute most labels under /usr on the host.

Processes running witht he svirt_lxc_net_t are not allowed to open/write to any other labels on the system. It is not allowed to read any default labels in /var, /root, /home etc.

Basically, we want to allow the processes to read/execute system content, but we want to not allow it to use any "data" on the system unless it is in the container, by default.

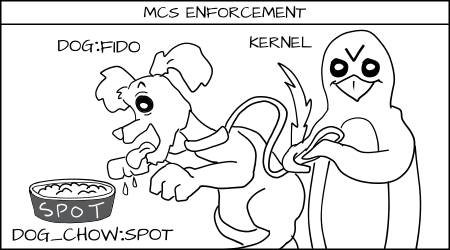

Problem

If all container processes are run with svirt_lxc_net_t and all content is labeled with svirt_sandbox_file_t, wouldn't container processes be allowed to attack processes running in other containers and content owned by other containers?

This is where Multi Category Security enforcement comes in, described below.

Alternate Types

Notice that we used "net" in the type label. We use this to indicate that this type can use full networking. I am working on a patch to Docker to allow users to specify alternate types to be used for containers. For example, you would be able to specify something like:

docker run -ti --security-opt label:type:lxc_nonet_t rhel7 /bin/sh

Then the processes inside of the container would not be allowed to use any network ports. Similarly, we could easily write an Apache policy that would only allow the container to listen on Apache ports, but not allowed to connect out on any ports. Using this type of policy you could prevent your container from becoming a spam bot even if it was cracked, and the hacker got control of the apache process within the container.

Multi Category Security enforcement

Multi Category Security (MCS) protects one container from other containers

Multi Category Security is based on Multi Level Security (MLS). MCS takes advantage of the last component of the SELinux label the MLS Field. MCS enforcement protects containers from each other. When containers are launched the Docker daemon picks a random MCS label, for example s0:c1,c2, to assign to the container. The Docker daemon labels all of the content in the container with this MCS label. When the daemon launches the container process it tells the kernel to label the processes with the same MCS label. The kernel only allows container processes to read/write their own content as long as the process MCS label matches the filesystem content MCS label. The kernel blocks container processes from read/writing content labeled with a different MCS label.

A hacked container process is prevented from attacking different containers. The Docker daemon is responsible for guaranteeing that no containers use the same MCS label. This is a video I made to show what would happen if an OpenShift container was able to get on root a system. The same basic policy is used to confine a Docker container.

As I mentioned above I am working on a patch to Docker to allow the specification of different SELinux content. I will be allowing administrators to specify the label of the container.

docker run --ti --rm --label-opt level:TopSecret rhel7 /bin/sh

This would allow people to start running containers in an Multi Level Security (MLS) environment, which could be useful for environments that require MLS.

SELinux gotchas

File system support

SELinux currently will only work with the device mapper back end. SELinux does not work with BTFS. BTRFS does not support context mount labeling yet, which prevents SELinux from relabeling all content when the container starts via the mount command. Kernel engineers are working on a fix for this and potentially Overlayfs if it gets merged into the container.

Volume mounts

Since Type Enforcement only allows container processes to read/write svirt_sandbox_file_t in containers, volume mounts can be a problem. A volume mount is just a bind mount of a directory into the container, there for the labels of the directory do not change. In order to allow the container processes to read/write the content you need to change the type label to svirt_sandbox_file_t.

Volume mounts /var/lib/myapp

chcon -Rt svirt_sandbox_file_t /var/lib/myapp

I have written a patch for docker that has not been merged upstream to set these labels automatically. With the patch you docker would relabel the volume to either a private label "Z" or a shared label "z" automatically.

docker run -v /var/lib/myapp:/var/lib/myapp:Z ...

docker run -v /var/lib/myapp:/var/lib/myapp:z ...

Hopefully this will get merged soon.

Bottom line

We have added lots of security mechanisms to make Docker containers more secure than running applications on bare metal, but you still need to maintain good security practices as I talked about in the first article on this subject.

- Only run applications from a trusted source

- Run applications on a enterprise quality host

- Install updates regularly

- Drop privileges as quickly as possible

- Run as non-root whenever possible

- Watch your logs

- setenforce 1

My next article on Docker security will cover what we are working on next to further secure Docker containers.

1 Comment