Emacs is a text editor designed for POSIX operating systems and available on Linux, BSD, macOS, Windows, and more. Users love Emacs because it features efficient commands for common but complex actions and for the plugins and configuration hacks that have developed around it for nearly 40 years.

Because it's an old editor that was developed well before modern computer conventions and terminology existed (for instance, you "visit" instead of "opening" a file, and you "write" instead of "save," and so on), Emacs is often viewed as complex and even mysterious. As time has shown, however, once you learn the basics, you have a powerful, efficient, and extremely hackable editor for life.

What is GNU Emacs?

In the early days of computing, word processors didn't exist at all, and text editors barely did. A text editor is essentially a word processor without any of the decoration like fancy fonts and page styles or page layouts.

[Download the Emacs cheat sheet]

Early text editors were so rudimentary that they couldn't even open an entire text document at once. Instead, a text editor was a command that could generate words and dump them into a file, or find and replace words in a file, or remove lines from a file, and so on. Editing big documents this way can get tedious, so people started developing macros to perform common, related tasks. In 1983, Richard Stallman released a bundle of his macros under the name editing macros, or emacs for short. When Dr. Stallman started the GNU project, Emacs became one of its most successful applications.

Today, although there are other emacsen (the plural of "emacs" is "emacsen"), the most common version of Emacs is GNU Emacs.

Features

Computer enthusiasts don't love Emacs just because it happens to be old and free. Emacs' appeal crosses industries and interests for the following reasons.

Easy on system resources

Compared to modern programming editors, Emacs is fairly lightweight. It used to be considered an unusually large tool for what it did, but with modern editors using web browser engines and JavaScript servers as their backends, a "simple" editor written in C and Lisp hardly makes a dent on system resources. Still, it does a lot more than just text editing.

Keyboard bindings

Learning Emacs can be difficult because it uses keyboard combinations fundamentally different from the way modern computers do. There's a method to this apparent madness, though, because Emacs is built to be flexible in how it's used. This includes devices without traditional keyboards and over networks that may not transmit modifier keys (such as Ctrl and Alt) correctly.

By default, Emacs keybindings revolve mostly around the Ctrl and Alt keys. In the documentation, the Ctrl key is represented as C and the Alt key as M (because before the Alt key was called "Alt," it was called "Meta"). When you need to press the Ctrl key and another key together, the action is written as, for example, C-x (meaning Ctrl+X) or C-c (Ctrl+C). The same goes for Alt/Meta: if you're meant to press Alt-X, then the notation is M-x.

Some keyboard bindings are combinations of several key presses. For instance, to open a file, you press C-x to enter command mode, and then C-f to find the file you want to open. To split your editing window (called a "buffer" in Emacs) horizontally, you press C-x and then the number 2.

Nearly every action in Emacs is a Lisp function and can be bound to a keyboard combination. If there's a function you want to invoke that hasn't been bound yet, you can just type the name of the function into the command buffer, much as you would launch an application from a Linux terminal. For instance, to activate Python mode, you press M-x, then type python-mode, and press Return (that's RET, in Emacs notation).

If you're on a device that doesn't have an Alt key, you can substitute the Esc key, but it behaves differently than the Alt key: You must press and release Esc and then press and release the accompanying key. For example, if you need to press M-x (Alt+X), to use the Esc key workaround, you would first press and release Esc and then press and release X. If your device has no Alt or Esc key, you can remap your keys as needed.

Getting used to the idea that every action is a function, and that any function can be invoked with a combination of keyboard shortcuts, is the primary learning curve in Emacs. At first, you might panic each time you want to take any action because even if you remember the first part of the keyboard combination, there's still the next part to remember. It's a little like learning to play piano, though, both mentally and physically. Once the keyboard interactions start to feel natural, it unlocks a whole new style of interfacing with the application. Editor commands blur into the act of transferring thoughts into words, so there's no separation between generating content and editing the content. This holds true, at least in my experience, when editing code and creative or personal documents.

It takes practice, but once you've learned it, you've got it for good.

Flexible

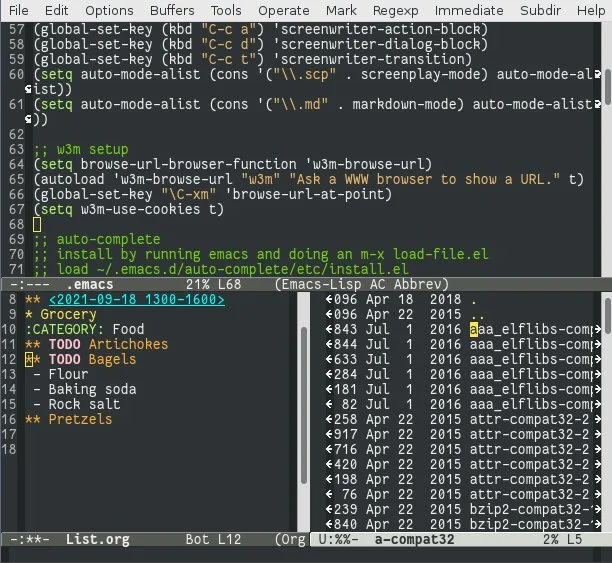

Emacs can be run in a GUI or within a terminal window. A GUI makes Emacs easier to learn, but the terminal version is important for sysadmins and web developers or anyone who needs to edit text remotely.

Emacs can also be used as a client, meaning you can launch Emacs in the background and then connect to it from another window or another machine.

Portable

Because it's written with modular code, it's trivial to build Emacs in a truly minimal form with few dependencies, which makes it easy to port to other systems. For this reason, it's unusual to find a computer system, old or new, popular or niche, that can't run Emacs or at least a minimal build of Emacs. If you're not committed to GNU Emacs, you can find extremely portable versions that require no more than a C library and terminal interface.

Emacs modes

Emacs has a convention of modes, which are essentially plugins that make Emacs behave differently for whatever activity you happen to be doing in it. For instance, there's Org mode for organizing your life and managing a calendar, Deft mode for taking notes, Fountain mode for writing screenplays, Muse for writing papers and articles, SES for spreadsheets, Python mode for Python code, Shell script mode (Sh mode) for Bash editing, nXML mode for XML editing, and many, many more.

In addition to modes, there are applications written for Emacs. For instance, there's a shell to run commands on the system running Emacs, a text-based file manager to browse files, an image viewer, a multimedia player, a Git interface, an email client, a rudimentary illustration interface to help draw flowcharts, and more.

Whatever you want to do in Emacs, there's probably a mode or package to help you do it (you can even play Tetris in it).

Open source and hacking

The most programmable applications today, it seems, are office spreadsheets. There are people with no programming experience whatsoever who manage to design elaborate and stunningly effective applications built with formulas and macros.

There's a limit to what a spreadsheet can produce, though, so if your idea for a helpful application doesn't quite fit into a grid, then it may work better as plain text. Emacs is only accidentally a text editor. Although it began its life as a collection of useful macros meant to edit text, the architecture of the application starts with C code that produces a Lisp interpreter. This means Emacs is actually a sandbox for Lisp code, meaning that if you learn Elisp, you can alter the application you're running while it's still running. You don't have to download the source code or compile after each change. You can create your own environment instantly and as subtly or severely as you please.

This, to many users, is the very embodiment of open source. You can build upon work others have created, you can look into the code that's affecting your workspace, and you can change it. It's a gateway to discovering how you can take control of the tools you use every day and customize them so that they work for you. While it's true that this gateway is only open to those willing to look at Lisp code (which is often considered old-fashioned), it's an important cultural stance to take, in which you expect that there's an easy and instantaneous avenue to view the source code of what you're using and that the source code is documented and hackable.

Get started

If Emacs sounds like it could solve some computing problems for you, there are lots of resources to learn it. If you're on Linux or BSD, you can install Emacs from your distribution's repository or ports tree. On Mac, you can download and install it from the GNU Emacs website, and Windows users can follow along with this how-to. Once you've installed it, find a way to learn it that suits your personal learning style. Sacha Chua offers an illustrated guide, and I created an audio tour and an introductory tutorial. And to help you keep track of what you learn, download Opensource.com's Emacs cheat sheet.

Thanks to the following contributors on Mastodon for helping with this resource page:

- @lorabe @quey.org

- @vertigo @mastodon.social

- @suetanvil

- @epicmorphism @satania.space

- @CarlCravens

- @gamayun @mastodon.social

- @vk @mamot.fr

- @vu3rdd @octodon.social

- @tfb @functional.cafe

- @gnomon @mastodon.social

- @dracoMetallium @pleroma.soykaf.com

- @technomancy @icosahedron.website