I work on a lot of servers, and sometimes I find a host that hasn't installed GNU Emacs. There's usually a GNU Nano installation to keep me from resorting to Vi, but I'm not used to Nano the way I am Emacs, and I inevitably run into complications when I try to save my document (C-x in Nano stands for Exit, and C-s locks Konsole).

While it would be nice to have GNU Emacs available everywhere, it's a lot of program for making a simple update to a config file. My need for a small and lightweight emacs is what took me down the path of discovering MicroEmacs, Jove, and Zile—tiny, self-contained emacsen that you can put on a thumb drive, an SD card, and nearly any server, so you'll never be without an emacs editor.

Editing macros

The term "emacs" is a somewhat generic term in the way that only open source produces, and a portmanteau. Before there was GNU Emacs, there were collections of batch process scripts (called macros) that could perform common tasks for a user. For instance, if you often found yourself typing "teh" instead of "the," you could either go in and correct each one manually (no small feat when your editor can't even load the entire document into memory, as was often the case in the early 1980s), or you could invoke a macro to perform a quick swap of the "e" and "h."

Eventually, these macros were bundled together into a package called editing macros, or EMACS for short. GNU Emacs is the most famous emacsen (yes, the -en suffix is used to describe many emacs, as in the word "oxen"), but it's not the only one. And it's certainly not the smallest. Quite the contrary, GNU Emacs is probably one of the largest.

Fortunately, GNU Emacs is so popular that other emacs implementations tend to mimic most of the GNU version's basic controls. If you're looking for a basic, fast, and efficient editor that isn't Vim, you'll likely be happy with any of these options.

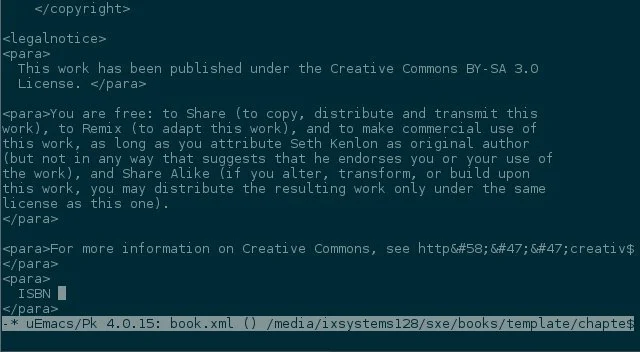

MicroEmacs

MicroEmacs, also known as uemacs (as in the Greek letter µ, which denotes "micro" in scientific notation), was written by Dave Conroy, but there's a long list of users who have cloned it and modified it. One user who maintains a personal version of µemacs is a programmer named Linus Torvalds, and his copy is available from his website, kernel.org (which also, incidentally, includes a small side project of his called Linux).

Size

It takes me five seconds to compile µemacs at the slowest setting I can impose on my computer, and the resulting binary is a mere 493KB. Admittedly, that's not literally "micro" compared to the typical size of a GNU Emacs download (1 millionth of 70MB is 70 bytes, by my calculation), but it's respectably small. For instance, it's easy enough to send it to yourself by email or over Signal, and certainly small enough to keep handy on every thumb drive or SD card you own.

By default, Linus's version expects libcurses, but you can override this setting in the Makefile so that it uses libtermcap instead. The resulting binary is independent enough to run on most Linux boxes:

$ ldd em

linux-vdso.so.1

libtermcap.so.2 => /lib64/libtermcap.so.2

libc.so.6 => /lib64/libc.so.6

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2Features

The keyboard shortcuts are just as you'd expect. You can open files and edit them without ever realizing you're not in GNU Emacs.

Some advanced features are missing. For instance, there's no vertical buffer split, although there is a horizontal split. There's no eval command, so you won't use µemacs for Lisp programming.

The search function is also a little different from what you may be used to: instead of C-s, it's M-s, which could make all the difference if your terminal emulator accepts Ctrl+S as a freeze command. The help page for µemacs is very complete, so use M-x help to get familiar with what it has available.

License

The license for µemacs is custom to the project with a non-commercial condition. You're free to share, use, and modify µemacs, but you can't do anything commercial with it.

While not as liberal a policy as I typically prefer, it's a good-enough license for personal use; just don't build a business around it.

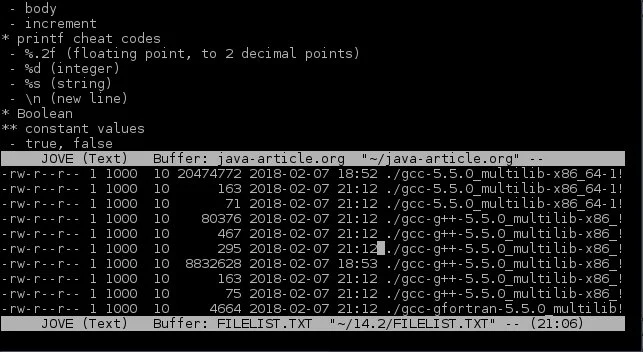

GNU Zile

GNU Zile claims to be a development kit for text editors. It's meant as a framework to enable people to quickly develop their own custom text editor without having to reinvent common data structures. It's a great idea and probably very useful, but as I have no interest in making my own editor, I just use the example implementation that ships with its codebase as a pleasant, lightweight emacs.

The build process for the example editor (supposedly called Zemacs, although the binary it renders is named zile) is the standard Autotools procedure:

$ ./configure

$ makeSize

Compiling it from source takes me a minute on one core or about 50 seconds on six cores (the configuration process is the long part). The binary produced in the end is 1.2MB, making this the heaviest of the lightweight emacsen I use, but compared to even GNU Emacs without X (which is 14MB on my system), it's relatively trivial.

Of the lightweight emacsen I use, it's also the most complex. You can exclude some library links by disabling features during configuration, but here are the defaults:

$ ldd src/zile

linux-vdso.so.1

libacl.so.1 => /lib64/libacl.so.1

libncurses.so.5 => /lib64/libncurses.so.5

libgc.so.1 => /usr/lib64/libgc.so.1

libc.so.6 => /lib64/libc.so.6

libattr.so.1 => /lib64/libattr.so.1

libdl.so.2 => /lib64/libdl.so.2

libpthread.so.0 => /lib64/libpthread.so.0

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2Features

Zile acts a little more like GNU Emacs than µemacs or Jove, but it's still a minimal experience. But some little touches are refreshing: Tab completion happens in a buffer, you can run shell commands from the mini-buffer, and you have a good assortment of functions available. It's by no means a GNU Emacs replacement, though, and if you wander too far in search of advanced features, you'll find out why it's only 1.2MB.

I've been unable to find in-application help files, and the man page bundled with it is minimal. However, if you're comfortable with Emacs, Zile is a good compromise between the full 14MB (or greater, if you're using a GUI) version and the extremely lightweight implementations.

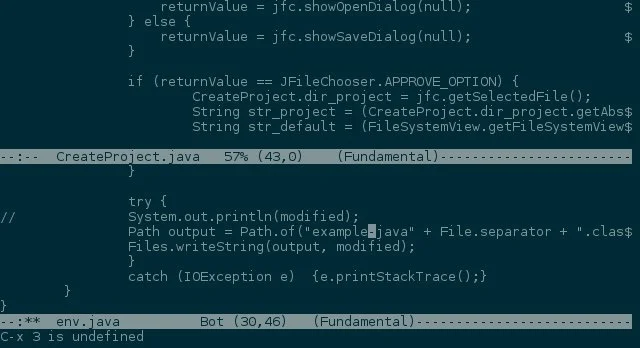

Jove

Jove was my first tiny emacs and remains the smallest I've found yet. This was an easy discovery for me, as it ships with Slackware Linux and, with a surreptitious symlink, quickly became my personal replacement for the Vi binary. Jove is based on GNU Emacs, but the man page cautions that feature parity is by no means to be expected. I find Jove surprisingly feature-rich for such a small binary (in fact, this article was written in Jove version 4.17.06-9), but there's no question that renaming .emacs to .joverc does not behave as you might hope.

Size

It takes me five seconds to compile Jove at the slowest setting (-j1) and about a second using all cores. The resulting binary, confusingly called jjove by default, is just 293KB.

The Jove binary is independent enough to run on most Linux boxes:

$ ldd jjove

linux-vdso.so.1

libtermcap.so.2 => /lib64/libtermcap.so.2

libc.so.6 => /lib64/libc.so.6

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2Features

Jove has good documentation in the form of a man page. You can also get a helpful listing of all available commands by typing M-x ? and using the Spacebar to scroll. If you're entirely new to emacs, you can run teachjove to learn Jove (and emacs, accordingly).

Most common editing commands and keybindings work as expected. Some oddities exist; for example, there's no vertical split, and Tab completion for paths in the mini-buffer is non-existent. However, it's the smallest emacs I've found and yet has a full GNU Emacs feel to it.

Try Emacs

If you've only ever tried GNU Emacs, then you might find that the world of emacsen is richer than you may have expected. There's a rich tradition behind emacs, and trying some of its variants, spin-offs, and alternate implementations is part of the joy of being comfortable with how emacsen work. Get to know emacs; carry a few builds around everywhere you go, and you'll never have to use a substandard editor again!

10 Comments