Last spring a group I follow on Facebook started sharing information about an oil pipeline, called the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), that was planned to go in the ground in North Dakota, and the Water Protectors, teenagers from the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation who were standing up to try to stop that from happening. As I watched the story unfold over the next few months, I knew that I wanted to go out there and see how the nonprofit organization I work for, Geeks Without Bounds, could help.

Geeks Without Bounds (GWOB) exists to help support open source humanitarian technology in low resource areas through education and hackathons so that communities can solve the challenges they face using tools that they fully own and control. For several years we'd been talking about how almost all of our work has been done overseas, but the United States has many low resource areas of its own. While we've done work around disaster response in the United States, including support for Occupy Sandy, data hackathons after disasters, and a project with the American Red Cross to modernize its incident reporting and management system, the work we've done in other countries is much more wide-ranging, from water issues in Tanzania and Uganda, to gender-based violence and human trafficking in India, to providing educational resources for remote communities in the Amazon.

The Oceti Sakowin Camp as seen from the Sicangu (Rosebud) Camp. Lisha Sterling, CC BY-SA.

When we looked at the Water Protector camps at Standing Rock, we saw a low resource community that would need many of the types of solutions that we've worked on in other environments. We also saw a space where any educational initiatives we worked on might have far-reaching impact, as members of tribes from throughout the United States could work and learn with us and then take those lessons home to their own communities. The GWOB strategy for projects like this, where we haven't been specifically asked for help in advance, is to reach out to community members to find out if it's appropriate for us to come help, then make a pilot trip where we gather information about the needs and wants of the community, before putting together a plan about how we can work together to meet the challenges at hand.

Before heading out to Standing Rock, we knew that one major need at the camps there was internet access. As spring turned to summer, reports were coming back that the people posting to social media had to travel 10 miles to the Prairie Knights Casino to get online. A mutual friend introduced me to Roberto Monge, a technologist who lives in southern California, who was also planning to travel to North Dakota to provide technical support to the community. He was also concerned about the lack of internet access and wanted to see what he could do to help fix that.

We got on the phone and talked for over an hour about the various ways we might be able to approach this. At the time, the strategy I was envisioning was to find a local internet provider that would be willing to work with us, and then to provide mobile phone connectivity and internet through a mesh network based on the LDLN project, which was part of the GWOB Accelerator program in 2014.

LDLN is a Raspberry Pi-based project that was built in response to Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in November 2013. Islands that were affected by the typhoon had a complete breakdown of communication, which made response and rescue much more difficult. The builders of LDLN created a tool that would allow a disaster-response organization to show up after an event with a large box of these little devices and create an instant mesh network that provides both a mobile phone network and a basic network infrastructure for the disaster zone. If one of the boxes is also connected to the internet, say through a satellite connection or a fiber line in an unaffected zone adjacent to the disaster, the whole network is then connected to the internet as well.

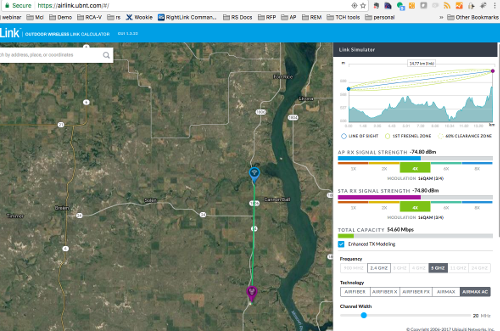

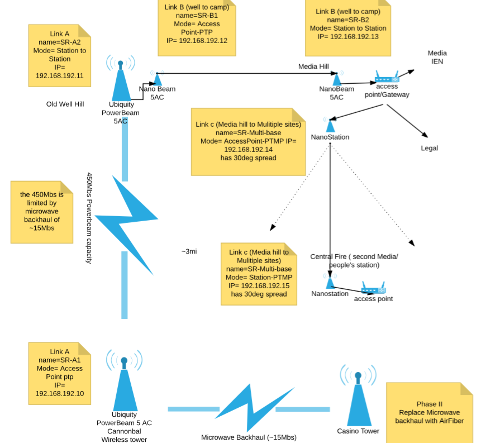

After a bit of research, Roberto discovered that the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation had its own mobile phone and internet company, called Standing Rock Telecom. Roberto suggested that we could bring internet from the casino to the main camp using Ubiquiti PowerBeams, and from there we could use the LDLN devices to provide network connectivity throughout the rest of the camps. Roberto used a tool from Ubiquiti that uses map data to figure out the best placement of the devices to get line-of-sight connection and provides an estimate of network throughput for the connection.

The Ubiquiti network planning tool with the information we needed to set up the network. Lisha Sterling, CC BY.

We knew that we could either use the firmware that comes stock with the Ubiquiti PowerBeams and NanoBeams or we could flash them all with the fully open source dd-wrt or OpenWRT, giving us more freedom overall. We were agnostic in terms of what the folks on the ground would choose, since we didn't think we'd be at camp for very long, and we needed to make sure that whoever took over the system's management learned how to run everything before we left. (Little did I know at that point that I would still be at camp months later!)

Before either of us went to Standing Rock, Roberto had connected with the Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN), which was managing press access at the camps, and arranged for us to work directly with them when we arrived. They were also working with Standing Rock Telecom at that point, and had arranged to have a 3G MiFi device and a cellphone booster set up on what was variously called Media Hill or Facebook Hill at the Oceti Sakowin camp. It was the home of IEN's media tent and also became the place where everyone went to catch any bit of network connection to get calls and Facebook posts out to the world without leaving camp.

In the research we did before heading to North Dakota, we learned that we could bring internet into camp from Standing Rock Telecom with one PowerBeam set up on one of the company's cell towers next to the casino and one PowerBeam set up on the hill just to the south of camp. That point, which would later be nicknamed Hop Hill, would then need another access point to send the connection down into camp. For that we would use the Ubiquiti NanoBeam, which we imagined we would point towards Media Hill or to a location more centrally located in camp, such as the area near the Sacred Fire.

Our first network map looked like this:

Original network map for Standing Rock. Drawing by Roberto Monge, CC BY-SA

Since we knew that the community definitely wanted internet, and we were pretty sure that the elders would approve our plan for bringing connectivity into camp, Roberto started a fundraiser to pay for the Ubiquiti equipment along with solar panels, deep cell batteries, and metal boxes to protect the power and network equipment from the elements. Knowing that we needed to get this started right away, he made a heroic leap of faith and purchased $7,000 worth of equipment with his own credit card to get us started!

The best laid plans of mice and men...

In the next part of this series, I'll explain how landing on the ground drastically changed our plans and why it took a full month to get our first internet connection into camp.

Comments are closed.