Large, multi-site, internet-facing systems, including content-delivery networks (CDNs) and cloud providers, have several options for balancing traffic coming onto their networks. In this article, we'll describe common traffic-balancing designs, including techniques and trade-offs.

If you were an early cloud computing provider, you could take a single customer web server, assign it an IP address, configure a domain name system (DNS) record to associate it with a human-readable name, and advertise the IP address via the border gateway protocol (BGP), the standard way of exchanging routing information between networks.

It wasn't load balancing per se, but there probably was load distribution across redundant network paths and networking technologies to increase availability by routing around unavailable infrastructure (giving rise to phenomena like asymmetric routing).

Doing simple DNS load balancing

As traffic to your customer's service grows, the business' owners want higher availability. You add a second web server with its own publicly accessible IP address and update the DNS record to direct users to both web servers (hopefully somewhat evenly). This is OK for a while until one web server unexpectedly goes offline. Assuming you detect the failure quickly, you can update the DNS configuration (either manually or with software) to stop referencing the broken server.

Unfortunately, because DNS records are cached, around 50% of requests to the service will likely fail until the record expires from the client caches and those of other nameservers in the DNS hierarchy. DNS records generally have a time to live (TTL) of several minutes or more, so this can create a significant impact on your system's availability.

Worse, some proportion of clients ignore TTL entirely, so some requests will be directed to your offline web server for some time. Setting very short DNS TTLs is not a great idea either; it means higher load on DNS services plus increased latency because clients will have to perform DNS lookups more often. If your DNS service is unavailable for any reason, access to your service will degrade more quickly with a shorter TTL because fewer clients will have your service's IP address cached.

Adding network load balancing

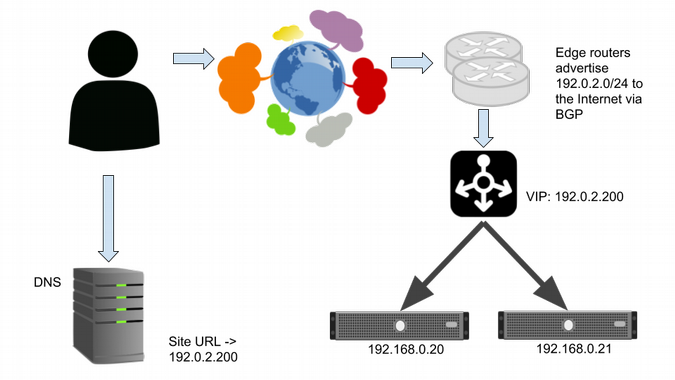

To work around this problem, you can add a redundant pair of Layer 4 (L4) network load balancers that serve the same virtual IP (VIP) address. They could be hardware appliances or software balancers like HAProxy. This means the DNS record points only at the VIP and no longer does load balancing.

Layer 4 load balancers balance connections from users across two webservers.

The L4 balancers load-balance traffic from the internet to the backend servers. This is generally done based on a hash (a mathematical function) of each IP packet's 5-tuple: the source and destination IP address and port plus the protocol (such as TCP or UDP). This is fast and efficient (and still maintains essential properties of TCP) and doesn't require the balancers to maintain state per connection. (For more information, Google's paper on Maglev discusses implementation of a software L4 balancer in significant detail.)

The L4 balancers can do health-checking and send traffic only to web servers that pass checks. Unlike in DNS balancing, there is minimal delay in redirecting traffic to another web server if one crashes, although existing connections will be reset.

L4 balancers can do weighted balancing, dealing with backends with varying capacity. L4 balancing gives significant power and flexibility to operators while being relatively inexpensive in terms of computing power.

Going multi-site

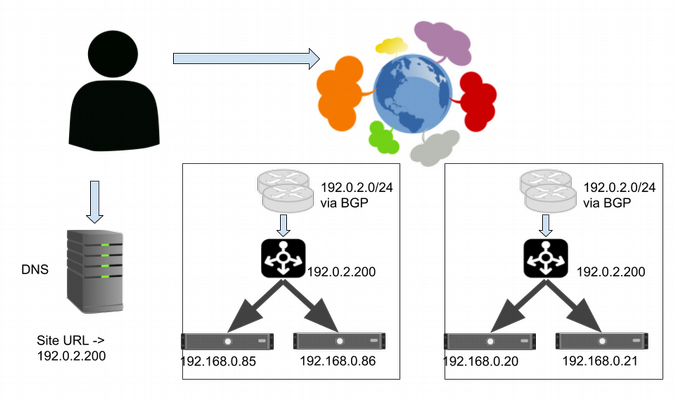

The system continues to grow. Your customers want to stay up even if your data center goes down. You build a new data center with its own set of service backends and another cluster of L4 balancers, which serve the same VIP as before. The DNS setup doesn't change.

The edge routers in both sites advertise address space, including the service VIP. Requests sent to that VIP can reach either site, depending on how each network between the end user and the system is connected and how their routing policies are configured. This is known as anycast. Most of the time, this works fine. If one site isn't operating, you can stop advertising the VIP for the service via BGP, and traffic will quickly move to the alternative site.

Serving from multiple sites using anycast.

This setup has several problems. Its worst failing is that you can't control where traffic flows or limit how much traffic is sent to a given site. You also don't have an explicit way to route users to the nearest site (in terms of network latency), but the network protocols and configurations that determine the routes should, in most cases, route requests to the nearest site.

Controlling inbound requests in a multi-site system

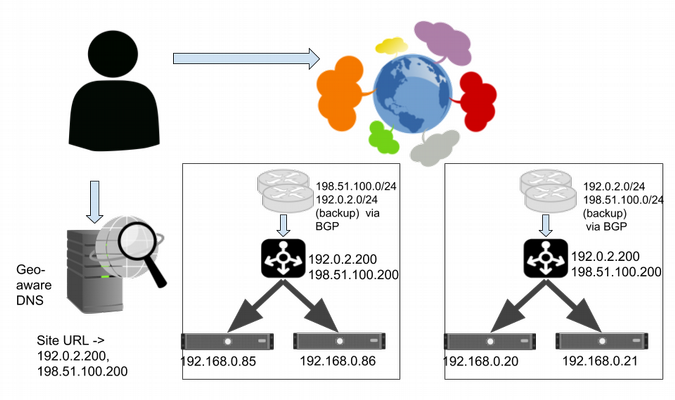

To maintain stability, you need to be able to control how much traffic is served to each site. You can get that control by assigning a different VIP to each site and use DNS to balance them using simple or weighted round-robin.

Serving from multiple sites using a primary VIP per site, backed up by secondary sites, with geo-aware DNS.

You now have two new problems.

First, using DNS balancing means you have cached records, which is not good if you need to redirect traffic quickly.

Second, whenever users do a fresh DNS lookup, a VIP connects them to the service at an arbitrary site, which may not be the closest site to them. If your service runs on widely separated sites, individual users will experience wide variations in your system's responsiveness, depending upon the network latency between them and the instance of your service they are using.

You can solve the first problem by having each site constantly advertise and serve the VIPs for all the other sites (and consequently the VIP for any faulty site). Networking tricks (such as advertising less-specific routes from the backups) can ensure that VIP's primary site is preferred, as long as it is available. This is done via BGP, so we should see traffic move within a minute or two of updating BGP.

There isn't an elegant solution to the problem of serving users from sites other than the nearest healthy site with capacity. Many large internet-facing services use DNS services that attempt to return different results to users in different locations, with some degree of success. This approach is always somewhat complex and error-prone, given that internet-addressing schemes are not organized geographically, blocks of addresses can change locations (e.g., when a company reorganizes its network), and many end users can be served from a single caching nameserver.

Adding Layer 7 load balancing

Over time, your customers begin to ask for more advanced features.

While L4 load balancers can efficiently distribute load among multiple web servers, they operate only on source and destination IP addresses, protocol, and ports. They don't know anything about the content of a request, so you can't implement many advanced features in an L4 balancer. Layer 7 (L7) load balancers are aware of the structure and contents of requests and can do far more.

Some things that can be implemented in L7 load balancers are caching, rate limiting, fault injection, and cost-aware load balancing (some requests require much more server time to process).

They can also balance based on a request's attributes (e.g., HTTP cookies), terminate SSL connections, and help defend against application layer denial-of-service (DoS) attacks. The downside of L7 balancers at scale is cost—they do more computation to process requests, and each active request consumes some system resources. Running L4 balancers in front of one or more pools of L7 balancers can help with scaling.

Conclusion

Load balancing is a difficult and complex problem. In addition to the strategies described in this article, there are different load-balancing algorithms, high-availability techniques used to implement load balancers, client load-balancing techniques, and the recent rise of service meshes.

Core load-balancing patterns have evolved alongside the growth of cloud computing, and they will continue to improve as large web services work to improve the control and flexibility that load-balancing techniques offer./p>

Laura Nolan and Murali Suriar will present Keeping the Balance: Load Balancing Demystified at LISA18, October 29-31 in Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Comments are closed.