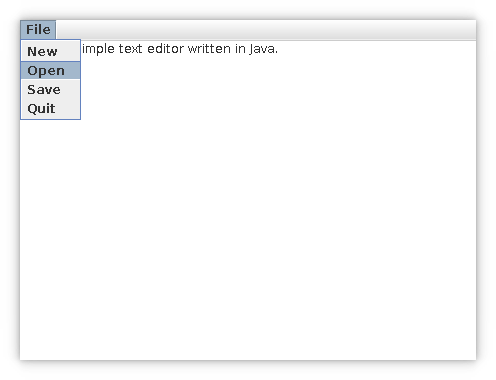

There are a lot of text editors available. There are those that run in the terminal, in a GUI, in a browser, and in a browser engine. Many are very good, and some are great. But sometimes, the most satisfying answer to any question is the one you build yourself.

Make no mistake: building a really good text editor is a lot harder than it may seem. But then again, it’s also not as hard as you might fear to build a basic one. In fact, most programming toolkits already have most of the text editor parts ready for you to use. The components around the text editing, such as a menu bar, file chooser dialogues, and so on, are easy to drop into place. As a result, a basic text editor is a surprisingly fun and elucidating, though intermediate, lesson in programming. You might find yourself eager to use a tool of your own construction, and the more you use it, the more you might be inspired to add to it, learning even more about the programming language you’re using.

To make this exercise realistic, it’s best to choose a language with a good GUI toolkit. There are many to choose from, including Qt, FLTK, or GTK, but be sure to review the documentation first to ensure it has the features you expect. For this article, I use Java with its built-in Swing widget set. If you want to use a different language or a different toolset, this article can still be useful in giving you an idea of how to approach the problem.

Writing a text editor in any major toolkit is surprisingly similar, no matter which one you choose. If you’re new to Java and need further information on getting started, read my Guessing Game article first.

Project setup

Normally, I use and recommend an IDE like Netbeans or Eclipse, but I find that, when practicing a new language, it can be helpful to do some manual labor, so you better understand the things that get hidden from you when using an IDE. In this article, I assume you’re programming using a text editor and a terminal.

Before getting started, create a project directory for yourself. In the project folder, create one directory called src to hold your source files.

$ mkdir -p myTextEditor/src

$ cd myTextEditorCreate an empty file called TextEdit.java in your src directory:

$ touch src/TextEditor.javaOpen the file in your favorite text editor (I mean your favorite one that you didn’t write) and get ready to code!

Package and imports

To ensure your Java application has a unique identifier, you must declare a package name. The typical format for this is to use a reverse domain name, which is particularly easy should you actually have a domain name. If you don’t, you can use local as the top level. As usual for Java and many languages, the line is terminated with a semicolon.

After naming your Java package, you must tell the Java compiler (javac) what libraries to use when building your code. In practice, this is something you usually add to as you code because you rarely know yourself what libraries you need. However, there are some that are obvious beforehand. For instance, you know this text editor is based around the Swing GUI toolkit, so importing javax.swing.JFrame and javax.swing.UIManager and other related libraries is a given.

package com.example.textedit;

import javax.swing.JFileChooser;

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JMenu;

import javax.swing.JMenuBar;

import javax.swing.JMenuItem;

import javax.swing.JOptionPane;

import javax.swing.JTextArea;

import javax.swing.UIManager;

import javax.swing.UnsupportedLookAndFeelException;

import javax.swing.filechooser.FileSystemView;

import java.awt.Component;

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import java.io.File;

import java.io.FileNotFoundException;

import java.io.FileReader;

import java.io.FileWriter;

import java.io.IOException;

import java.util.Scanner;

import java.util.logging.Level;

import java.util.logging.Logger;For the purpose of this exercise, you get prescient knowledge of all the libraries you need in advance. In real life, regardless of what language you favor, you’ll discover libraries as you research how to solve any given problem, and then you’ll import it into your code and use it. And don’t worry—should you forget to include a library, your compiler or interpreter will warn you!

Main window

This is a single-window application, so the primary class of this application is a JFrame with an ActionListener attached to catch menu events. In Java, when you’re using an existing widget element, you "extend" it with your code. This main window needs three fields: the window itself (an instance of JFrame), an indicator for the return value of the file chooser, and the text editor itself (JTextArea).

public final class TextEdit extends JFrame implements ActionListener {

private static JTextArea area;

private static JFrame frame;

private static int returnValue = 0;Amazingly, these few lines do about 80% of the work toward implementing a basic text editor because JTextArea is Java’s text entry field. Most of the remaining 80 lines take care of helper features, like saving and opening files.

Building a menu

The JMenuBar widget is designed to sit at the top of a JFrame, providing as many entries as you want. Java isn’t a drag-and-drop programming language, though, so for every menu you add, you must also program a function. To keep this project manageable, I provide four functions: creating a new file, opening an existing file, saving text to a file, and closing the application.

The process of creating a menu is basically the same in most popular toolkits. First, you create the menubar itself, then you create a top-level menu (such as "File"), and then you create submenu items (such as "New," "Save," and so on).

public TextEdit() { run(); }

public void run() {

frame = new JFrame("Text Edit");

// Set the look-and-feel (LNF) of the application

// Try to default to whatever the host system prefers

try {

UIManager.setLookAndFeel(UIManager.getSystemLookAndFeelClassName());

} catch (ClassNotFoundException | InstantiationException | IllegalAccessException | UnsupportedLookAndFeelException ex) {

Logger.getLogger(TextEdit.class.getName()).log(Level.SEVERE, null, ex);

}

// Set attributes of the app window

area = new JTextArea();

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

frame.add(area);

frame.setSize(640, 480);

frame.setVisible(true);

// Build the menu

JMenuBar menu_main = new JMenuBar();

JMenu menu_file = new JMenu("File");

JMenuItem menuitem_new = new JMenuItem("New");

JMenuItem menuitem_open = new JMenuItem("Open");

JMenuItem menuitem_save = new JMenuItem("Save");

JMenuItem menuitem_quit = new JMenuItem("Quit");

menuitem_new.addActionListener(this);

menuitem_open.addActionListener(this);

menuitem_save.addActionListener(this);

menuitem_quit.addActionListener(this);

menu_main.add(menu_file);

menu_file.add(menuitem_new);

menu_file.add(menuitem_open);

menu_file.add(menuitem_save);

menu_file.add(menuitem_quit);

frame.setJMenuBar(menu_main);

}

All that’s left to do now is to implement the functions described by the menu items.

Programming menu actions

Your application responds to menu selections because your JFrame has an ActionListener attached to it. When you implement an event handler in Java, you must "override" its built-in functions. This sounds more severe than it actually is. You’re not rewriting Java; you’re just implementing functions that have been defined but not implemented by the event handler.

In this case, you must override the actionPerformed method. Because nearly all entries in the File menu have something to do with files, my code defines a JFileChooser early. The rest of the code is separated into clauses of an if statement, which looks to see what event was received and acts accordingly. Each clause is drastically different from the other because each item suggests something wholly unique. The most similar are Open and Save because they both use the JFileChooser to select a point in the filesystem to either get or put data.

The "New" selection clears the JTextArea without warning, and Quit closes the application without warning. Both of these "features" are dangerous, so should you want to make a small improvement to this code, that’s a good place to start. A friendly warning that the content hasn’t been saved is a vital feature of any good text editor, but for simplicity’s sake, that’s a feature for the future.

@Override

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent e) {

String ingest = null;

JFileChooser jfc = new JFileChooser(FileSystemView.getFileSystemView().getHomeDirectory());

jfc.setDialogTitle("Choose destination.");

jfc.setFileSelectionMode(JFileChooser.FILES_AND_DIRECTORIES);

String ae = e.getActionCommand();

if (ae.equals("Open")) {

returnValue = jfc.showOpenDialog(null);

if (returnValue == JFileChooser.APPROVE_OPTION) {

File f = new File(jfc.getSelectedFile().getAbsolutePath());

try{

FileReader read = new FileReader(f);

Scanner scan = new Scanner(read);

while(scan.hasNextLine()){

String line = scan.nextLine() + "\n";

ingest = ingest + line;

}

area.setText(ingest);

}

catch ( FileNotFoundException ex) { ex.printStackTrace(); }

}

// SAVE

} else if (ae.equals("Save")) {

returnValue = jfc.showSaveDialog(null);

try {

File f = new File(jfc.getSelectedFile().getAbsolutePath());

FileWriter out = new FileWriter(f);

out.write(area.getText());

out.close();

} catch (FileNotFoundException ex) {

Component f = null;

JOptionPane.showMessageDialog(f,"File not found.");

} catch (IOException ex) {

Component f = null;

JOptionPane.showMessageDialog(f,"Error.");

}

} else if (ae.equals("New")) {

area.setText("");

} else if (ae.equals("Quit")) { System.exit(0); }

}

}That’s technically all there is to this text editor. Of course, nothing’s ever truly done, and besides, there’s still the testing and packaging steps, so there’s still plenty of time to discover missing requisites. In case you’re not picking up on the hint: there’s definitely something missing in this code. Do you know what it is yet? (It’s mentioned mainly in the Guessing Game article.)

Testing

You can now test your application. Launch your text editor from a terminal:

$ java ./src/TextEdit.java

error: can’t find main(String[]) method in class: com.example.textedit.TextEditIt seems that the code hasn’t got a main method. There are a few ways to fix this problem: you could create a main method in TextEdit.java and have it run an instance of the TextEdit class, or you can create a separate file containing the main method. Both work equally well, but the latter is more realistic in terms of what to expect from large projects, so it’s worth getting used to dealing with separate files that work together to make a complete application.

Create a Main.java file in src and open in your favorite editor:

package com.example.textedit;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

TextEdit runner = new TextEdit();

}

}You can try again, but now there are two files that depend upon one another to run, so you have to compile the code. Java uses the javac compiler, and you can set your destination directory with the -d option:

$ javac src/*java -d .This creates a new directory structure modeled exactly after your package name: com/example/textedit. This new classpath contains the files Main.class and TextEdit.class, which are the two files that make up your application. You can run them with java by referencing the location and name (not the filename) of your Main class:

$ java info/slackermedia/textedit/MainYour text editor opens, and you can type into it, open files, and even save your work.

Sharing your work as a Java package

While it seems to be acceptable to some programmers to deliver applications as an assortment of source files and hearty encouragement to learn how to run them, Java makes it really easy to package up your application so others can run it. You have most of the structure required, but you do need to add some metadata to a Manifest.txt file:

$ echo "Manifest-Version: 1.0" > Manifest.txtThe jar command, used for packaging, is a lot like the tar command, so many of the options may look familiar to you. To create a JAR file:

$ jar cvfme TextEdit.jar

Manifest.txt

com.example.textedit.Main

com/example/textedit/*.classFrom the syntax of the command, you may surmise that it creates a new JAR file called TextEdit.jar, with its required manifest data located in Manifest.txt. Its main class is defined as an extension of the package name, and the class itself is com/example/textedit/Main.class.

You can view the contents of the JAR file:

$ jar tvf TextEdit.jar

0 Wed Nov 25 META-INF/

105 Wed Nov 25 META-INF/MANIFEST.MF

338 Wed Nov 25 com/example/textedit/textedit/Main.class

4373 Wed Nov 25 com/example/textedit/textedit/TextEdit.classAnd you can even extract it with the xvf options, if you’d like to see how your metadata has been integrated into the MANIFEST.MF file.

Run your JAR file with the java command:

$ java -jar TextEdit.jarYou can even create a desktop file, so your application launches at the click of an icon in your applications menu.

Improve it

In its current state, this is a very basic text editor, best suited for quick notes or short README documents. Some improvements (such as adding a vertical scrollbar) are quick and easy with a little research, while others (such as implementing an extensive preferences system) require real work.

But if you’ve been meaning to learn a new language, this could be the perfect practical project for your self-education. Creating a text editor, as you can see, isn’t overwhelming in terms of code, and it’s manageable in scope. If you use text editors frequently, then writing your own can be satisfying and fun. So open your favorite text editor (the one you wrote) and start adding features!

1 Comment