WebAssembly is a bytecode format that virtually every browser can compile to its host system's machine code. Alongside JavaScript and WebGL, WebAssembly fulfills the demand for porting applications for platform-independent use in the web browser. As a compilation target for C++ and Rust, WebAssembly enables web browsers to execute code at near-native speed.

When you talk about a WebAssembly, application, you must distinguish between three states:

- Source code (e.g., C++ or Rust): You have an application written in a compatible language that you want to execute in the browser.

- WebAssembly bytecode: You choose WebAssembly bytecode as your compilation target. As a result, you get a

.wasmfile. - Machine code (opcode): The browser loads the

.wasmfile and compiles it to the corresponding machine code of its host system.

WebAssembly also has a text format that represents the binary format in human-readable text. For the sake of simplicity, I will refer to this as WASM-text. WASM-text can be compared to high-level assembly language. Of course, you would not write a complete application based on WASM-text, but it's good to know how it works under the hood (especially for debugging and performance optimization).

This article will guide you through creating the classic Hello World program in WASM-text.

Creating the .wat file

WASM-text files usually end with .wat. Start from scratch by creating an empty text file named helloworld.wat, open it with your favorite text editor, and paste in:

(module

;; Imports from JavaScript namespace

(import "console" "log" (func $log (param i32 i32))) ;; Import log function

(import "js" "mem" (memory 1)) ;; Import 1 page of memory (54kb)

;; Data section of our module

(data (i32.const 0) "Hello World from WebAssembly!")

;; Function declaration: Exported as helloWorld(), no arguments

(func (export "helloWorld")

i32.const 0 ;; pass offset 0 to log

i32.const 29 ;; pass length 29 to log (strlen of sample text)

call $log

)

)The WASM-text format is based upon S-expressions. To enable interaction, JavaScript functions are imported with the import statement, and WebAssembly functions are exported with the export statement. For this example, import the log function from the console module, which takes two parameters of type i32 as input and one page of memory (64KB) to store the string.

The string will be written into the data section at offset 0. The data section is an overlay of your memory, and the memory is allocated in the JavaScript part.

Functions are marked with the keyword func. The stack is empty when entering a function. Function parameters are pushed onto the stack (here offset and length) before another function is called (see call $log). When a function returns an f32 type (for example), an f32 variable must remain on the stack when leaving the function (but this is not the case in this example).

Creating the .wasm file

The WASM-text and the WebAssembly bytecode have 1:1 correspondence. This means you can convert WASM-text into bytecode (and vice versa). You already have the WASM-text, and now you want to create the bytecode.

The conversion can be performed with the WebAssembly Binary Toolkit (WABT). Make a clone of the repository at that link and follow the installation instructions.

After you build the toolchain, convert WASM-text to bytecode by opening a console and entering:

wat2wasm helloworld.wat -o helloworld.wasmYou can also convert bytecode to WASM-text with:

wasm2wat helloworld.wasm -o helloworld_reverse.watA .wat file created from a .wasm file does not include any function nor parameter names. By default, WebAssembly identifies functions and parameters with their index.

Compiling the .wasm file

Currently, WebAssembly only coexists with JavaScript, so you have to write a short script to load and compile the .wasm file and do the function calls. You also need to define the functions you will import in your WebAssembly module.

Create an empty text file and name it helloworld.html, then open your favorite text editor and paste in:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Simple template</title>

</head>

<body>

<script>

var memory = new WebAssembly.Memory({initial:1});

function consoleLogString(offset, length) {

var bytes = new Uint8Array(memory.buffer, offset, length);

var string = new TextDecoder('utf8').decode(bytes);

console.log(string);

};

var importObject = {

console: {

log: consoleLogString

},

js : {

mem: memory

}

};

WebAssembly.instantiateStreaming(fetch('helloworld.wasm'), importObject)

.then(obj => {

obj.instance.exports.helloWorld();

});

</script>

</body>

</html>The WebAssembly.Memory(...) method returns one page of memory that is 64KB in size. The function consoleLogString reads a string from that memory page based on the length and offset. Both objects are passed to your WebAssembly module as part of the importObject.

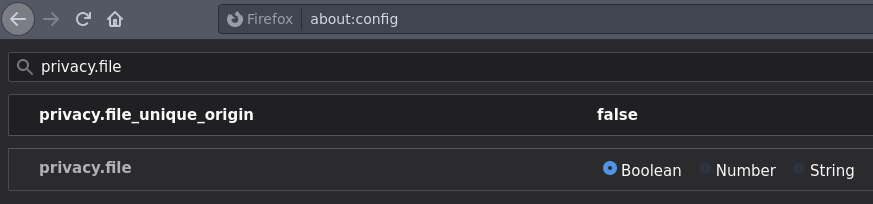

Before you can run this example, you may have to allow Firefox to access files from this directory by typing about:config in the address line and setting privacy.file_unique_origin to true:

(Stephan Avenwedde, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Caution: This will make you vulnerable to the CVE-2019-11730 security issue.

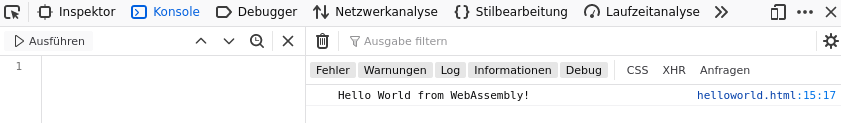

Now, open helloworld.html in Firefox and enter Ctrl+K to open the developer console.

(Stephan Avenwedde, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Learn more

This Hello World example is just one of the detailed tutorials in MDN's Understanding WebAssembly text format documentation. If you want to learn more about WebAssembly and how it works under the hood, take a look at these docs.

Comments are closed.