"Why Clojure?" is probably the question we've been asked the most at Penpot. We have a vague explanation on our FAQ page, so with this article, I'll explain the motivations and spirit behind our decision.

It all started in a PIWEEK. Of course!

During one of our Personal Innovation Weeks (PIWEEK) in 2015, a small team had the idea to create an open source prototyping tool. They started work immediately, and were able to release a working prototype after a week of hard work (and lots of fun). This was the first static prototype, without a backend.

I was not part of the initial team, but there were many reasons to choose ClojureScript back then. Building a prototype in just a one-week hackathon isn't easy and ClojureScript certainly helped with that, but I think the most important reason it was chosen was because it's fun. It offered a functional paradigm (in the team, there was a lot of interest in functional languages).

It also provided a fully interactive development environment. I’m not referring to post-compilation browser auto-refresh. I mean refreshing the code at runtime without doing a page refresh and without losing state! Technically, you could be developing a game, and change the behavior of the game while you are still playing it, just by touching a few lines in your editor. With ClojureScript (and Clojure) you don't need anything fancy. The language constructs are already designed with hot reload in mind from the ground up.

(Andrey Antukh, CC BY-SA 4.0)

I know, today (in 2022), you can also have something similar with React on plain JavaScript, and probably with other frameworks that I’m not familiar with. Then again, it's also probable that this capability support is limited and fragile, because of intrinsic limitations in the language, sealed modules, the lack of a proper REPL.

About REPL

In other dynamic languages, like JavaScript, Python, Groovy (and so on), REPL features are added as an afterthought. As a result, they often have issues with hot reloading. The language patterns are fine in real code, but they aren't suitable in the REPL (for example, a const in JavaScript evaluates the same code twice in a REPL).

These REPLs are usually used to test code snippets made for the REPL. In contrast, REPL usage in Clojure rarely involves typing or copying into the REPL directly, and it is much more common to evaluate small code snippets from the actual source files. These are frequently left in the code base as comment blocks, so you can use the snippets in the REPL again when you change the code in the future.

In the Clojure REPL, you can develop an entire application without any limitations. The Clojure REPL doesn't behave differently from the compiler itself. You're able to do all kinds of runtime introspection and hot replacement of specific functions in any namespace in an already running application. In fact, it's not uncommon to find backend applications in a production environment exposing REPL on a local socket to be able to inspect the runtime and, when necessary, patch specific functions without even having to restart the service.

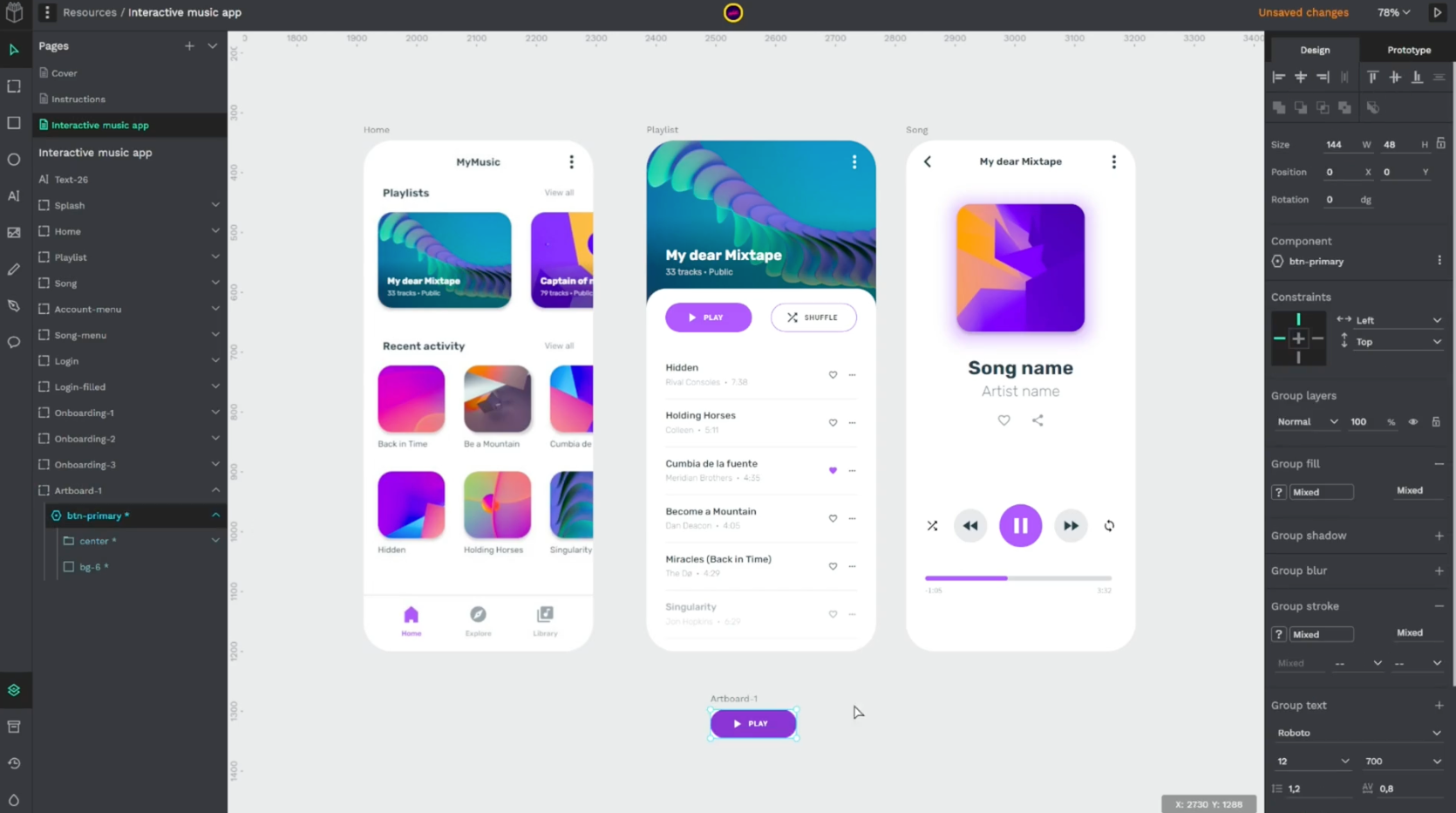

From prototype to the usable application

After PIWEEK in 2015, Juan de la Cruz (a designer at Penpot, and the original author of the project idea) and I started working on the project in our spare time. We rewrote the entire project using all the lessons learned from the first prototype. At the beginning of 2017, we internally released what could be called the second functional prototype, this time with a backend. And the thing is, we were still using Clojure and ClojureScript!

The initial reasons were still valid and relevant, but the motivation for such an important time investment reveals other reasons. It's a very long list, but I think the most important features of all were: stability, backwards compatibility, and syntactic abstraction (in the form of macros).

(Andrey Antukh, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Stability and backwards compatibility

Stability and backwards compatibility are one of the most important goals of the Clojure language. There's usually not much of a rush to include all the trendy stuff into the language without having tested its real usefulness. It's not uncommon to see people running production on top of an alpha version of the Clojure compiler, because it's rare to have instability issues even on alpha releases.

In Clojure or ClojureScript, if a library doesn't have commits for some time, it's most likely fine as is. It needs no further development. It works perfectly, and there's no use in changing something that functions as intended. Contrarily, in the JavaScript world, when you see a library that hasn't had commits in several months, you tend to get the feeling that the library is abandoned or unmaintained.

There are numerous times when I've downloaded a JavaScript project that has not been touched in 6 months only to find that more than half of the code is already deprecated and unmaintained. On other occasions, it doesn’t even compile because some dependencies have not respected semantic versioning.

This is why each dependency of Penpot is carefully chosen, with continuity, stability, and backwards compatibility in mind. Many of them have been developed in-house. We delegate to third party libraries only when they have proven to have the same properties, or when the effort to time ratio of doing it in-house wasn't worth it.

I think a good summary is that we try to have the minimum necessary external dependencies. React is probably a good example of a big external dependency. Over time, it has shown that they have a real concern with backwards compatibility. Each major release incorporates changes gradually and with a clear path for migration, allowing for old and new code to coexist.

Syntactic abstractions

Another reason I like Clojure is its clear syntactic abstractions (macros). It's one of those characteristics that, as a general rule, can be a double-edged sword. You must use it carefully and not abuse it. But with the complexity of Penpot as a project, having the ability to extract certain common or verbose constructs has helped us simplify the code. These statements cannot be generalized, and the possible value they provide must be seen on a case-by-case basis. Here are a couple of important instances that have made a significant difference for Penpot:

- When we began building Penpot, React only had components as a class. But those components were modeled as functions and decorators in a

rumextlibrary. When React released versions with hooks that greatly enhanced the functional components, we only had to change the implementation of the macro and 90% of Penpot's components could be kept unmodified. Subsequently, we've gradually moved from decorators to hooks completely without the need for a laborious migration. This reinforces the same idea of the previous paragraphs: stability and backwards compatibility. - The second most important case is the ease of using native language constructs (vectors and maps) to define the structure of the virtual DOM, instead of using a JSX-like custom DSL. Using those native language constructs would make a macro end up generating the corresponding calls to

React.createElementat compile time, still leaving room for additional optimizations. Obviously, the fact that the language is expression-oriented makes it all more idiomatic.

Here's a simple example in JavaScript, based on examples from React documentation:

function MyComponent({isAuth, options}) {

let button;

if (isAuth) {

button = <LogoutButton />;

} else {

button = <LoginButton />;

}

return (

<div>

{button}

<ul>

{Array(props.total).fill(1).map((el, i) =>

<li key={i}>{{item + i}}</li>

)}

</ul>

</div>

);

}Here's the equivalent in ClojureScript:

(defn my-component [{:keys [auth? options]}]

[:div

(if auth?

[:& logout-button {}]

[:& login-button {}])

[:ul

(for [[i item] (map-indexed vector options)]

[:li {:key i} item])]])All these data structures used to represent the virtual DOM are converted into the appropriate React.createElement calls at compile time.

The fact that Clojure is so data-oriented made using the same native data structures of the language to represent the virtual DOM a natural and logical process. Clojure is a dialect of LISP, where the syntax and AST of the language use the same data structures and can be processed with the same mechanisms.

For me, working with React through ClojureScript feels more natural than working with it in JavaScript. All the extra tools added to React to use it comfortably, such as JSX, immutable data structures, or tools to work with data transformations, and state handling, are just a part of the ClojureScript language.

Guest Language

Finally, one of the fundamentals of Clojure and ClojureScript is that they were built as Guest Languages. That is, they work on top of an existing platform or runtime. In this case, Clojure is built on top of the JVM and ClojureScript on top of JavaScript, which means that interoperability between the language and the runtime is very efficient. This allowed us to take advantage of the entire ecosystem of both Clojure plus everything that's done in Java (the same is true for ClojureScript and JavaScript).

There are also pieces of code that are easier to write when they're written in imperative languages, like Java or JavaScript. Clojure can coexist with them in the same code base without any problems.

There's also an ease of sharing code between frontend and backend, even though each one can be running in a completely different runtime (JavaScript and JVM). For Penpot, almost all the most important logic for managing a file's data is written in code and executed both in the frontend and in the backend.

Perhaps you could say we have chosen what some people call a "boring" technology, but without it actually being boring at all.

Trade-offs

Obviously, every decision has trade-offs. The choice to use Clojure and ClojureScript is not an exception. From a business perspective, the choice of Clojure could be seen as risky because it's not a mainstream language, it has a relatively small community compared to Java or JavaScript, and finding developers is inherently more complicated.

But in my opinion, the learning curve is much lower than it might seem at first glance. Once you get rid of the it's different fear (or as I jokingly call it: fear of the parentheses), you start to gain fluency with the language very quickly. There are tons of learning resources, including books and training courses.

The real obstacle I have noticed is the paradigm shift, rather than the language itself. With Penpot, the necessary and inherent complexity of the project makes the programming language the least of our problems when facing development: building a design platform is no small feat.

This article originally appeared on the Kaleidos blog and has been republished with permission.

Comments are closed.