Touted as the most extensive revision of the patent law since 1952, the America Invents Act of 2011 was signed by the President on September 16. You might think in light of the celebration and rhetoric, that the Act was tackling the big problems such as patent trolls, broad and abstract patents, the billions squandered in the smartphone wars, or opportunistic litigation against users. You might think that. But you would be wrong.

A Not-So-Innovative Act

The great irony of the America Invents Act is that the big push for patent reform originally came from IT companies, but over the years the reform effort was channeled into fixing a few longstanding anomalies of the U.S. patent system:

- the lack of an effective post-grant invalidation option;

- our unique first-to-invent system; and

- congressional diversion of patent fees for other purposes.

So instead of providing alternatives to litigation as high-tech had asked, the Act adds a post-grant review process that must initiated within nine months. Similar opposition or invalidation proceedings have long been available in the European Patent Office and elsewhere. Meanwhile the Act actually trims back two procedures (ex parte reexamination and inter partes reexamination) that serve as limited alternatives to litigation.

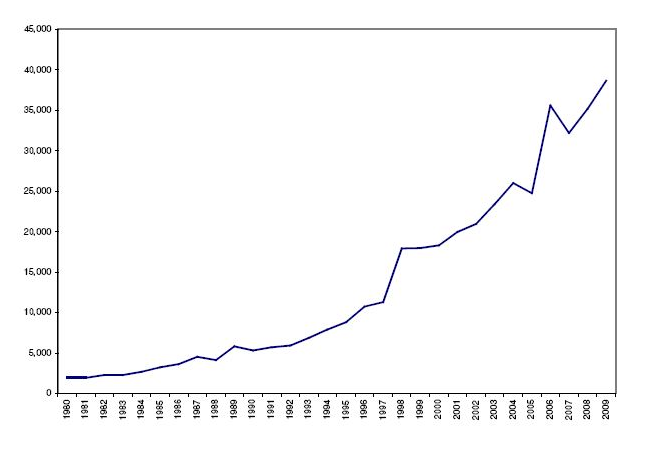

An immediate 9-month window for post-grant review is fine in some industries where patents are few and well-known. It is of little help in IT, where a single product may contain thousands of patentable functions and the government issues a torrent of patents every week – many with abstract, overlapping claims and of questionable quality. IT-related patents now account for nearly half the the 200,000+ U.S. patents each year, nearly four times the number granted by the European Patent Office. Software patents alone now total 40,000 patents each year, despite the fact that they are widely reviled by those who actually create software.

Annual Grants of Software Patents (source: James Bessen and Michael Meurer, A Generation of Software Patents)

Second, the Act adopts, at long last, the first-to-file system used in every other country in the world. Moving to first-to-file was recommended by the 1966 President’s Commission on the Patent System. It has been opposed by small entities and universities, who fear that large companies with well-oiled patent operations will beat them to the patent office. High-tech companies are worried that the added incentive for rushing to the patent office will result in even greater overpatenting.

Third, the Act sets up a reserve fund that makes it less likely (but not impossible) that Congress will divert patent fees to other purposes as it has done on occasion in the past, mostly prior to 2004. The Act gives the PTO greater fee-setting authority, but it reaffirms the current fee structure, which subsidizes patent applications and thereby encourages low-quality filings. The subsidy gives the PTO a powerful incentive to grant patents, since the costs of examination must be recovered from issuance and maintenance fees – fees that it receives only if it grants the patent. Worse, the new Act specifies that fees can only be used for the PTO’s internal costs. In other words, they cannot take into account the damage done from wrongly issued patents.

Subsidizing Value Destruction?

It has been widely claimed that speeding examination at the PTO will create hundreds of thousands of jobs. But if an invention is important, investors will do their own due diligence – and not simply rely on what a GS-5 examiner with a bachelor’s degree in science eventually has to say four years later after a few hours of searching. The examiner has the burden of proving that the patent should not be granted and suffers no repercussions for allowing bad patents to issue. Indeed, patents asserted by trolls are on average eight years old by the time suit is filed (11-12 years after the patent is applied for!) – by which time the examiner is probably working in the private sector.

Few companies are going to knowingly copy a genuine invention, because the patent will be granted and they then face the possibility of an injunction as well as damages. It’s the marginal patents that get a big boost, since granted patents get an enhanced presumption of validity that makes them hard to invalidate. In effect, this is yet another subsidy, which gives the applicant more than the cursory exam merits.

The subsidy doesn’t stop there. Despite claims that patents should be treated as property, they are not taxed as property at either local, state, or federal levels. Yet the public pays for growing costs for federal courts to evaluate validity, interpret claims, determine infringement, and assess damages. Industry (and ultimately the public) pays not only for the astronomical costs of patent litigation but for the uncertainty and damage that trolls do. A recent study shows that litigation by trolls diminishes the market valuation of public companies by $80 billion per year! $80 billion/year is a lot of jobs and innovation foregone – and nearly 50 times the budget of the PTO’s patent operation. The study also shows that 62% of the troll cases involved software patents.

Revenge of the Judicial Activists

To be fair, the America Invents Act does one thing to limit the options for trolls. It stops them from joining dozens of defendants in one lawsuit and hauling them all into the patent friendly Eastern District of Texas. They have done so on the grounds that the allegedly offending mass-market products are sold there (along with everywhere else) and one of the defendants is a local retailer. As a result, in terms of total number of patent defendants, the Eastern District of Texas outranks the next highest district court four-to-one. Here Congress actually overturned Eastern District of Texas case law, undoubtedly offending its judges. (Or at least it thought it did.)

Maybe Congress can get away with this affront to the favorite venue of patent trolls, but companies that advocate reform may not be so lucky. In a recent Eastern District of Texas case, the CEO of a Taiwanese defendant dared to voice his views, not in court but in Taiwan on the other side of the globe, saying "the issue of patent infringement is being taken too seriously sometimes." He might as well be speaking about trolls. Or the bureaucrats of the European Commission who keep trying to criminalize patent infringement – despite widespread opposition from industry. Or the U.S. International Trade Commission which, when it finds a single infringing function out of 10,000, issues exclusionary orders barring entire product lines.

However, the suggestion that patent infringement should not necessarily result in undue punishment so outraged Judge Ward that he doubled the damages – a windfall for the London-based "non-practicing entity" that sued on the patent. He wrote:

The court finds that this statement by InnoLux's CEO shows InnoLux's lack of respect for this court and the jury's verdict. It is also an affront to the United States patent system - a system of constitutional origin.

But the patent system is not mandated by the Constitution – no more than any of the other enumerated powers. Is the regulation of interstate commerce also so sacrosanct as to invite punishment for those who disagree with how agencies regulate it?

Unlike the patent system, free speech is not just something that Congress can provide for if it chooses. We do not want foreign courts half a world way punishing Americans for casual criticism of that country's practices, especially comments made here. Yet tinpot treatment of foreign defendants in the U.S. for they say at home invites other countries to reciprocate.

The growing criticism of absurdly broad, trivial, and abstract patents is undoubtedly also an affront to the US patent system. Patents on abstract subject matter are the legacy of decisions by the specialized Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, especially State Street Bank (1998), which abolished the longstanding exclusion of business methods.

In the course of debate over reform, leading Republicans on the House Judiciary Committee rightly denounced State Street as judicial activism, yet Congress could not muster the will to limit patents on any but the most egregious form, patents on compliance with the tax laws ("tax strategies"). And as the bill was awaiting passage in the Senate, the Chief Judge of the Federal Circuit, joined by the court’s longest serving judge, made it clear that he didn't want to hear arguments limiting the scope of patentable subject matter. Not in an opinion but in separate "additional views" that could not be appealed to the Supreme Court:

This court should decline to accept invitations to restrict subject matter eligibility .... Excluding categories of subject matter from the patent system achieves no substantive improvement in the patent landscape ....

What about the rest of the landscape? Shouldn’t there be some creative and innovative activities where you do not have to read patents first and consult routinely with lawyers?

By creating obstacles to patent protection, the real-world impact is to frustrate innovation and drive research funding to more hospitable locations. To be direct, if one nation makes patent protection difficult, it will drive research to another, more accommodating nation.

The Judge offers no references or empirical evidence but simply equates research with patents. Readers of the study on the costs of trolls may find it more intuitive to substitute "litigation" for "innovation," "legal funding" for "research funding," and "drive lawyers" for "drive research."

But this is the Chief Judge of the patent appeals court – the court that gave the world patents on business methods, software, diagnostic information, everything...And he’s saying: Don’t ask for limits to the patent system. We’re not listening.

Touted as the most extensive revision of the patent law since 1952, the America Invents Act of 2011 was signed by the President on September 16. You might think in light of the celebration and rhetoric, that the Act was tackling the big problems such as patent trolls, broad and abstract patents, the billions squandered in the smartphone wars, or opportunistic litigation against users. You might think that. But you would be wrong.

A Not-So-Innovative Act

The great irony of the America Invents Act is that the big push for patent reform originally came from IT companies, but over the years the reform effort was channeled into fixing a few longstanding anomalies of the U.S. patent system:

the lack of an effective post-grant invalidation option;

our unique first-to-invent system; and

congressional diversion of patent fees for other purposes.

So instead of providing alternatives to litigation as high-tech had asked, the Act adds a post-grant review process that must initiated within nine months. Similar opposition or invalidation proceedings have long been available in the European Patent Office and elsewhere. Meanwhile the Act actually trims back two procedures (ex parte reexamination and inter partes reexamination) that serve as limited alternatives to litigation.

An immediate 9-month window for post-grant review is fine in some industries where patents are few and well-known. It is of little help in IT, where a single product may contain thousands of patentable functions and the government issues a torrent of patents every week – many with abstract, overlapping claims and of questionable quality. IT-related patents now account for nearly half the the 200,000+ U.S. patents each year, nearly four times the number granted by the European Patent Office. Software patents alone now total 40,000 patents each year, despite the fact that they are widely reviled by those who actually create software.

2 Comments