On April 18, Docker founder Solomon Hykes made a big announcement via a pull request in the main Docker repo: "Docker is transitioning all of its open source collaborations to the Moby project going forward." The docker/docker repo now redirects to moby/moby, and Solomon's pull request updates the README and logo for the project to match.

Reaction from the Docker community has been overwhelmingly negative. As of this writing, the Moby pull request has garnered 7 upvotes and 110 downvotes on GitHub. The Docker community is understandably frustrated by this opaque announcement of a fait accompli, an important decision that a hidden inner circle made behind closed doors. It's a textbook case of "Why wasn't I consulted?"

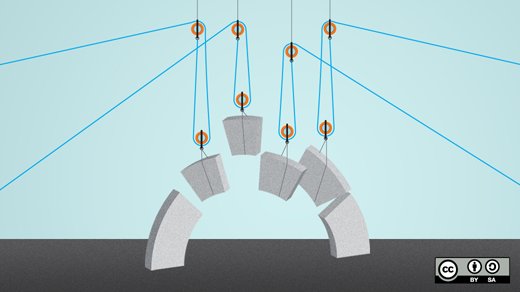

"Inner sourcing" refers to the application of open source principles within the walled garden of a closed organization. What Docker has done here seems something like the reverse, applying closed organization principles to an open source community.

Maybe we can call this "inner circling."

Inner circling can be a difficult tendency to resist. In fact, I've seen it crop up recently in several open source communities of which I'm a part, including the Sustain conference (key organizers hold a private weekly call), and even the Open Organization Ambassadors group (Red Hat editors privately control Opensource.com). It's something we all need to work on. Let's look at four questions that can clarify how to do better.

Who are you? There's a subtle (but important) difference between a closed organization that does some things openly, and an open organization that does some things privately. The former will naturally tend to make closed decisions unless the organization has an ulterior motive for operating openly in a particular situation. However, the more you identify with your community, the more that vetting decisions large and small before you consider them settled will become second nature. Where do you locate your identity? In the open with your community? Or behind closed doors with an inner circle?

Why did you reach this decision? Even an open organization must make some decisions privately. At Gratipay, for example, we've identified "legal, safety, security, and support matters" as the exceptions to the rule of open decision making. However, when announcing a closed decision publicly, explaining the thought process behind your decision will help your community to take your decision on board. When Gratipay had to reboot due to legal uncertainty, we went to great lengths to explain the complicated legal issues to the community. Yes, that's a lot of work. But it's worthwhile for preserving and even enhancing the community's trust.

Docker has some great reasons for renaming their open source project to Moby, and making the decision privately may even be reasonable. For instance, renaming Gittip to Gratipay required two epic bikesheds. With a community the size of Docker's, a public conversation could've become simply unmanageable (though Mozilla's recent open rebrand would suggest otherwise). Even just a few sentences by way of honest explanation could've turned some of those downvotes into upvotes.

Where do you make decisions? Let's assume for a moment that the Docker-to-Moby decision was made publicly (the pull request doesn't actually say). Where was it discussed? On a mailing list? Another GitHub issue? A Google Hangout? A link clearly labeled "more details" gives motivated individuals the ability to do their own research and answer their own questions. This also helps people better understand where they should pay attention to avoid surprises in the future.

How do you make decisions? Links to sources (or the lack thereof) give some implicit clues about how your organization makes decisions, but, to borrow from the Zen of Python, "Explicit is better than implicit." Jono Bacon's book, The Art of Community, includes a whole chapter on governance and decision-making. Recent conferences and books in the Platform Cooperativism movement have been exploring the relationship between cooperative governance models and open source. One way or another, setting clear expectations about how decisions are made builds trust.

Once the dust settles, rebranding the Docker open source project to Moby will probably turn out to have been a fine decision. However, a more open process for making that decision could have resulted in less dust in the first place. Had Docker avoided "inner circling"—importing closed decision making into an open community—their rebrand could have been a source of trust instead of tension.

5 Comments