As any programmer knows, there are many reasons it's vital to keep track of code changes. Sometimes you just want a history of how your project started and evolved, as a matter of curiosity or education. Other times, you want to enable other coders to contribute to your project, and you need a reliable way to merge disparate parts. And more critically, sometimes an adjustment you make to fix one problem breaks something else that was working.

The Fossil source code management system is an all-in-one version control system, bug tracker, wiki, forum, and documentation solution from the creator of the famous SQLite database.

Install Fossil

Fossil is a single, self-contained C program, so you can probably just download Fossil from its website and place it anywhere in your system PATH. For example, assuming /usr/local/bin is in your path, as it usually is by default:

$ wget https://fossil-scm.org/home/uv/fossil-linux-x64-X.Y.tar.gz

$ sudo tar xvf fossil-linux-x64-X.Y.tar.gz \

--directory /usr/local/binYou might also find Fossil in your software repository through your package manager, or you can compile it from source code.

Create a Fossil repository

If you have a coding project you want to track with Fossil, the first step is to create a Fossil repository:

$ fossil init myproject.fossil

project-id: 010836ac6112fefb0b015702152d447c8c1d8604

server-id: 54d837e9dc938ba1caa56d31b99c35a4c9627f44

admin-user: klaatu (initial password is "14b605")Creating a Fossil repo returns three items: a unique project ID, a unique server ID, and an admin ID and password. The project and server IDs are version numbers. The admin credentials establish your ownership of this repository and can be used if you decide to run Fossil as a server for other users to access.

Work in a Fossil repository

To start working in a Fossil repo, you must create a working location for its data. You might think of this process as creating a virtual environment in Python or unzipping a ZIP file that you intend to zip back up again later.

Create a working directory and change into it:

$ mkdir myprojectdir

$ cd myprojectdirOpen your Fossil repository into the directory you created:

$ fossil open ../myproject

project-name: <unnamed>

repository: /home/klaatu/myprojectdir/../myproject

local-root: /home/klaatu/myprojectdir/

config-db: /home/klaatu/.fossil

project-code: 010836ac6112fefb0b015702152d447c8c1d8604

checkout: 9e6cd96dd675544c58a246520ad58cdd460d1559 2020-11-09 04:09:35 UTC

tags: trunk

comment: initial empty check-in (user: klaatu)

check-ins: 1You might notice that Fossil created a hidden file called .fossil in your home directory to track your global Fossil preferences. This is not specific to your project; it's just an artifact of the first time you use Fossil.

Add files

To add files to your repository, use the add and commit subcommands. For example, create a simple README file and add it to the repository:

$ echo "My first Fossil project" > README

$ fossil add README

ADDED README

$ fossil commit -m 'My first commit'

New_Version: 2472a43acd11c93d08314e852dedfc6a476403695e44f47061607e4e90ad01aaUse branches

By default, a Fossile repository starts with a main branch called trunk. You can branch off the trunk when you want to work on code without affecting your primary codebase. Creating a new branch requires the branch subcommand, along with a new branch name and the branch you want to use as the basis for your new one. In this example, the only branch is trunk, so try creating a new branch called dev:

$ fossil branch --help

Usage: fossil branch new BRANCH-NAME BASIS ?OPTIONS?

$ fossil branch new dev trunk

New branch: cb90e9c6f23a9c98e0c3656d7e18d320fa52e666700b12b5ebbc4674a0703695You've created a new branch, but your current branch is still trunk:

$ fossil branch current

trunkTo make your new dev branch active, use the checkout command:

$ fossil checkout dev

devMerge changes

Suppose you add an exciting new file to your dev branch, and having tested it, you're satisfied that it's ready to take its place in trunk. This is called a merge.

First, change your branch back to your target branch (in this example, that's trunk):

$ fossil checkout trunk

trunk

$ ls

READMEYour new file (or any changes you made to an existing file) doesn't exist there yet, but that's what performing the merge will take care of:

$ fossil merge dev

"fossil undo" is available to undo changes to the working checkout.

$ ls

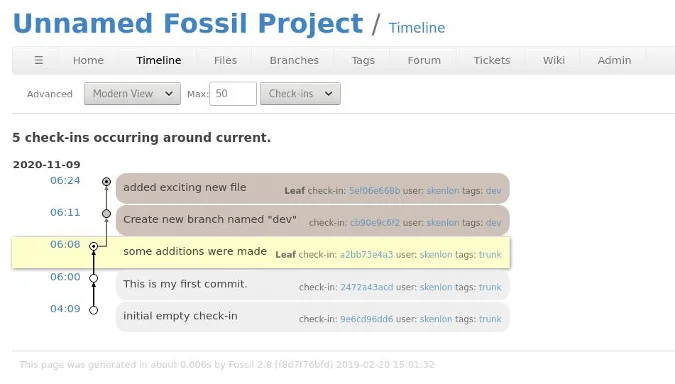

myfile.lua READMEView the Fossil timeline

To see the history of your repository, use the timeline option. This shows a detailed list of all activity in your repository, including a hash representing the change, the commit message you provided when committing code, and who made the change:

$ fossil timeline

=== 2020-11-09 ===

06:24:16 [5ef06e668b] added exciting new file (user: klaatu tags: dev)

06:11:19 [cb90e9c6f2] Create new branch named "dev" (user: klaatu tags: dev)

06:08:09 [a2bb73e4a3] *CURRENT* some additions were made (user: klaatu tags: trunk)

06:00:47 [2472a43acd] This is my first commit. (user: klaatu tags: trunk)

04:09:35 [9e6cd96dd6] initial empty check-in (user: klaatu tags: trunk)

+++ no more data (5) +++

(Klaatu, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Make your Fossil repository public

Because Fossil features a built-in web interface, Fossil doesn't need a hosting service like GitLab or Gitea do. Fossil is its own hosting service, as long as you have a server to put it on. Before making your Fossil project public, though, you must configure some attributes through the web user interface (UI).

Launch a local instance with the ui subcommand:

$ pwd

/home/klaatu/myprojectdir/

$ fossil uiSpecifically, look at Users and Settings for security, and Configuration for project properties (including a proper title). The web interface isn't just a convenience function. It's intended for actual use and is indeed used as the host for the Fossil project. There are several surprisingly advanced options, from user management (or self-management, if you please) to single-sign-on (SSO) with other Fossil repositories on the same server.

Once you're satisfied with your changes, close the web interface and press Ctrl+C to stop the UI engine from running. Commit your web changes just as you would any other update:

$ fossil commit -m 'web ui updates'

New_Version: 11fe7f2855a3246c303df00ec725d0fca526fa0b83fa67c95db92283e8273c60Now you're ready to set up your Fossil server.

- Copy your Fossil repository (in this example,

myproject.fossil) to your server. You only need the single file. - Install Fossil on your server, if it's not already installed. The process for installing Fossil to your server is the same as it was for your local computer.

- In your

cgi-bindirectory (or the equivalent of that directory, depending upon which HTTP daemon you're running), create a file calledrepo_myproject.cgi:

#!/usr/local/bin/fossil

repository: /home/klaatu/public_html/myproject.fossilMake the script executable:

$ chmod +x repo_myproject.cgiThat's all there is to it. Your project is now live on the internet.

You can visit the web UI by navigating to your CGI script, such as https://example.com/cgi-bin/repo_myproject.cgi.

Or you can interact with your repository from a terminal through the same URL:

$ fossil clone https://klaatu@example.com/cgi-bin/repo_myproject.cgiWorking with a local clone requires you to use the push subcommand to send local changes back to your remote repository and the pull subcommand to get remotely made changes into your local copy:

$ fossil push https://klaatu@example.com/cgi-bin/repo_myproject.cgiUse Fossil for independent hosting

Fossil places a lot of power into your hands (and the hands of your collaborators) and makes you independent of hosting services. This article only hints at the basics. There's so much more to Fossil that can help you and your teams in your code projects. Give Fossil a try. It won't just change the way you think about version control; it'll help you stop thinking about version control altogether.

Comments are closed.