Preparing to run a new (or convert an existing) application in Kubernetes takes work. Working with Kubernetes requires defining and creating multiple "manifests" for the different types of objects in your application. Even a simple microservice is likely to have a deployment.yaml, service.yaml, configmap.yaml, and other files. These declarative YAML files for Kubernetes are usually known as "manifests." You might also have to set up secrets, ingresses, persistent volumes, and other supporting pieces.

Once those are created, you're done with managing your manifests, right? Well, it depends. What happens if someone else needs to work with your manifest but needs a slightly (or significantly) different version? Or what happens if someone wants to leverage your manifests for different stages or environments? You need to handle reuse and updates for the different use cases without losing track of your original version.

Typical approaches for reusing manifests

Approaches for reusing manifests have typically been rather brute force. You make a copy, modify it in whatever way is appropriate, and save it with a different name or location. This process works for the immediate use case, but things can quickly get out of sync or become unwieldy to manage.

The copy approach

Suppose you want to change a manifest to add a new resource or update a value in a manifest copy. Someone or something will have to monitor the original, figure out the differences, and merge them into the copy.

The problem becomes even worse if other people make their own copies and change them to suit their particular use case. Very quickly, the content diverges. People might miss important or significant updates to the original manifests, and they might end up using confusing variations of similar files.

And over time, the situation can worsen, and a significant amount of time can be spent just trying to keep things up to date. If copies of the copies are made, you can end up with something that diverges significantly from the original and even lose track of what was in the original. This, in turn, can dramatically affect usability and maintainability.

The parameterization approach

Another approach is to create parameterized templates from the files. That is, to make the manifests into generic "templates" by replacing static, hardcoded values with placeholders that can be filled in with any value. Values are usually supplied at deployment time, with placeholders replaced by values passed in from a command line or read in from a data file. The resulting templates with the values filled in are rendered as valid manifests for Kubernetes.

This is the approach the well-known tool Helm takes. However, this also has challenges. Removing values and using placeholders fundamentally changes and adds complexity to the manifests, which are now templates. They are no longer usable on their own; they require an application or process like Helm to find or derive and fill in the values. And, as templates, the original files are no longer easily parsable by anyone who looks at them.

The templates are also still susceptible to the issues that copies of the files have. In fact, the problem can be compounded when using templates due to copies having more placeholders and separate data values stored elsewhere. Functions and pipes that join functions can also be added. At some level, this can turn the templates into sort of "programmed YAML" files. At the extreme, this may make the files unusable and unreadable unless you use Helm to render them with the data values into a form that people (and Kubernetes) can understand and use.

Kustomize's alternative approach

Ideally, you would be able to keep using your existing files in their original forms and produce variations without making permanent changes or copies that can easily diverge from the original and each other. And you would keep the differences between versions small and simple.

These are the basic tenets of Kustomize's approach. It's an Apache 2.0-licensed tool that generates custom versions of manifests by "overlaying" declarative specifications on top of existing ones. "Declarative" refers to the standard way to describe resources in Kubernetes: declaring what you want a resource to be and how to look and behave, in contrast to "imperative," which defines the process to create it.

"Overlaying" describes the process where separate files are layered over (or "stacked on top of") each other to create altered versions. Kustomize applies specific kinds of overlays to the original manifest. The changes to be made in the rendered versions are declared in a separate, dedicated file named kustomization.yaml, while leaving the original files intact.

Kustomize reads the kustomization.yaml file to drive its behavior. One section of the kustomization.yaml file, titled Resources, lists the names (and optionally the paths) of the original manifests to base changes on. After loading the resources, Kustomize applies the overlays and renders the result.

You can think of this as applying the specified customizations "on top of" a temporary copy of the original manifest. These operations produce a "customized" copy of the manifest that, if you want, can be fed directly into Kubernetes via a kubectl apply command.

The types of functions built into Kustomize "transform" your Kubernetes manifests, given a simple set of declarative rules. These sets of rules are called "transformers."

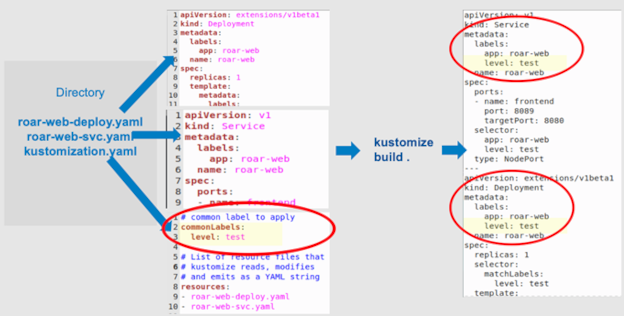

The simplest kind of transformer applies a common identifier to the same set of resources, as Figure 1 demonstrates.

Figure 1: A simple example (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

This example has a simple directory with a set of YAML files for a web app with a MySQL backend. The files are:

roar-web-deploy.yamlis the Kubernetes deployment manifest for the web app part of an app.roar-web-svc.yamlis the Kubernetes service manifest for the web app part of an app.kustomization.yamlis the Kustomize input file that declares the type of transformations you want to make to the manifests.

In the kustomization.yaml file in Figure 1, the commonLabels section (the bottom center) is an example of a transformer. As the name implies, this transformer's intent is to make the designated label common in the files after the transformation.

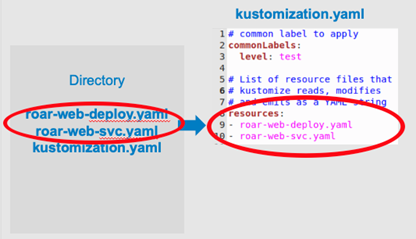

The kustomization.yaml file also includes a resources section, which lists the files to be included and possibly customized or transformed (highlighted in Figure 2).

Figure 2: Resources section in kustomization.yaml (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The kustomization.yaml file is a simple set of declarations about the manifests you want to change and how you want to change them; it is a specification of resources plus customizations. The modifications happen when you run the kustomize build command. The build operation reads the kustomization.yaml file, pulls in the resources, and applies the transformers appropriate to each file. This example pulls in the two roar-web YAML files, produces copies of them, and adds the requested label in the metadata section for each one.

By default, the files are not saved anywhere, and the original files are not overwritten. The "transformed" content can be piped directly to a kubectl apply command or redirected and saved to another file if you want. However, it's generally not a good idea to save generated files because it becomes too easy for them to get out of sync with the source. You can view the output from the kustomize build step as generated content.

Instead, you should save the associated original files and the kustomization.yaml file. Since the kustomization.yaml file pulls in the original files and transforms them for rendering, they can stay the same and be reused in their original form.

Other transformations

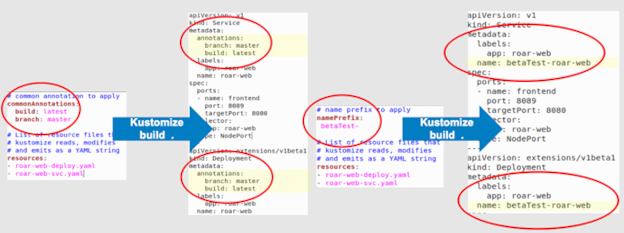

Kustomize provides a set of transformations that you can apply to a set of resources. These include:

commonLabeladds a common label (name:value) to each Kubernetes (K8s) resource.commonAnnotationsadds an annotation to all K8s resources.namePrefixadds a common prefix to all resource names.

Figure 3 shows examples of other types of common changes.

Figure 3: commonAnnotations and namePrefix transformers (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Image transformers

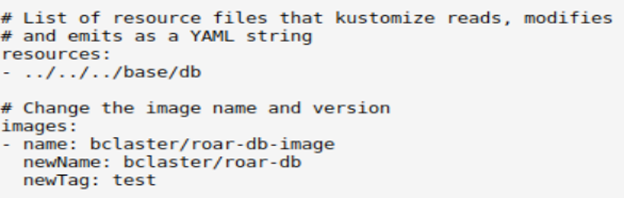

As its name implies, image transformers produce a version of a manifest with a different newname or newTag for an image spec, such as a container or an initcontainer. The name value must match the image value in the original resource.

Figure 4 shows an example of a kustomization.yaml file with changes for an image.

Figure 4: A kustomization.yaml file for an image transformer (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

While it's useful to do these kinds of transformations, a more strategic feature is creating separate versions for different environments from a set of resources. In Kustomize, these are called "variants."

Variants

In Kubernetes, it's common to need multiple variations (variants) of a set of resources and the manifests that declare them. A simple example is building on top of a set of Kubernetes resources to create different variants for different stages of product development, such as dev, stage, and prod.

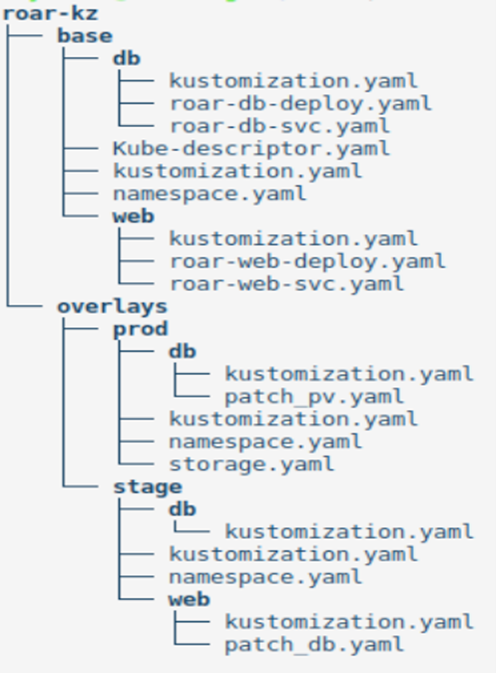

To facilitate these sorts of changes, Kustomize uses the concepts of "overlays" and "bases." A "base" declares things variants have in common, and an "overlay" declares differences between variants. Both bases and overlays are represented within a kustomization.yaml file. Figure 5 includes an example of this structure. It has the original resource manifests and a base kustomization.yaml file in the root of the tree. The kustomization.yaml files define variants as a set of overlays in subdirectories for prod and stage.

Figure 5: A structure utilizing the base/overlay approach (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Variants can also apply patches. Patches in Kustomize are a partial spec or a "delta" for a K8s object. They describe what a section should look like after it changes and how it should be modified when Kustomize renders an updated version. They represent a more "surgical" approach to targeting one or more specific sections in a resource.

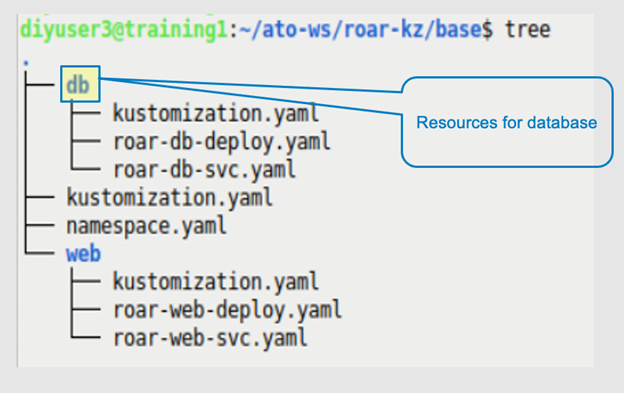

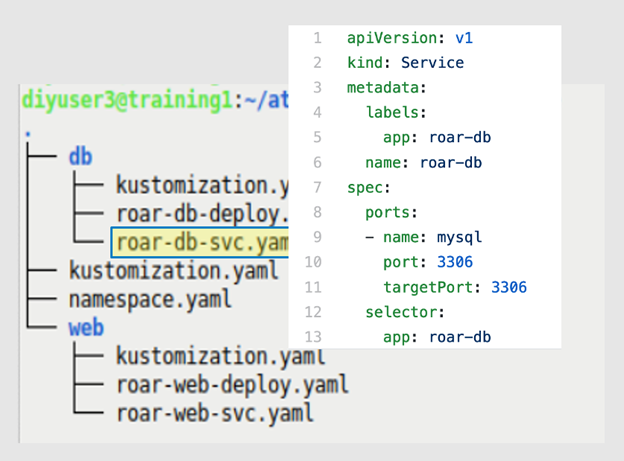

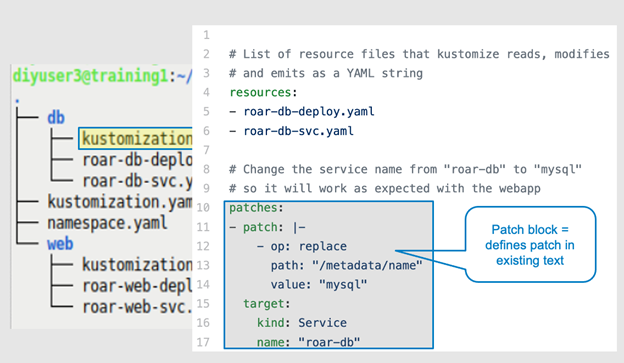

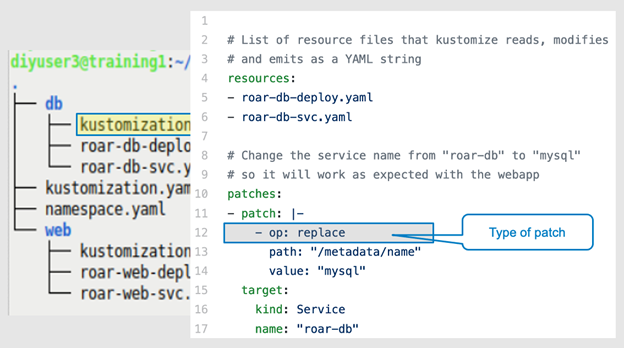

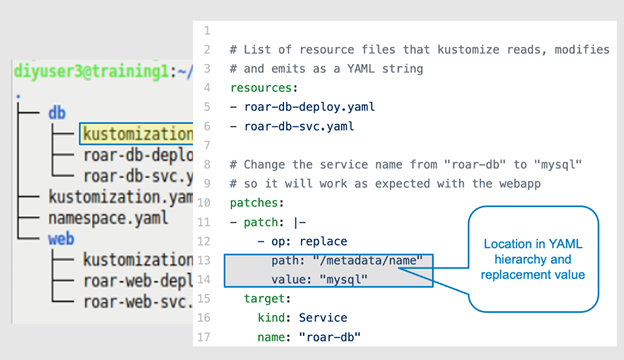

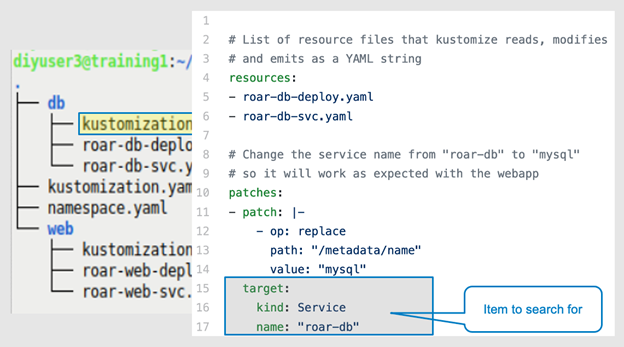

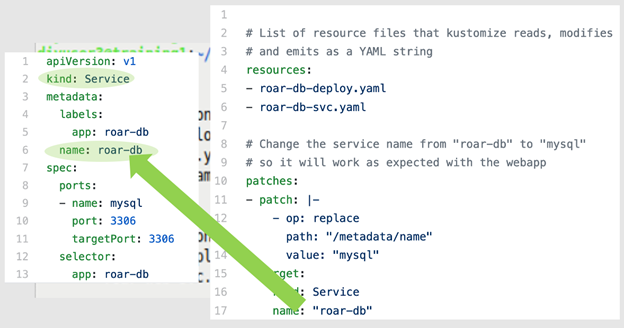

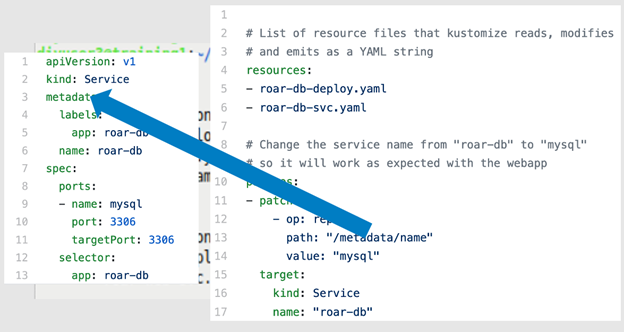

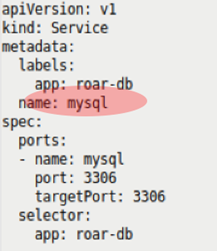

The next set of figures demonstrate leveraging the Kustomize patching functionality. Going back to an earlier example, you have a set of core resource files (a deployment and a service) and the associated kustomization.yaml files for them (Figures 6a and 6b). There are two parts to the app: a database portion and a web app portion. The patch in this example renames the database service.

Figures 6a and 6b: The app structure and the service definition to patch (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

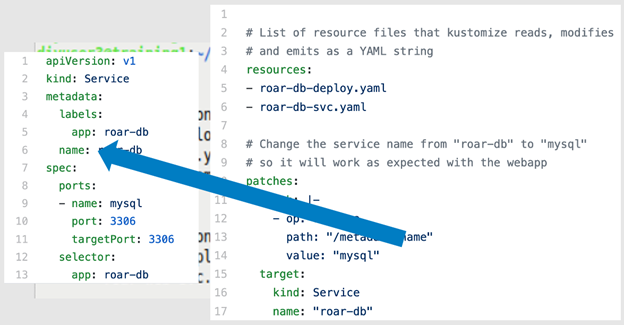

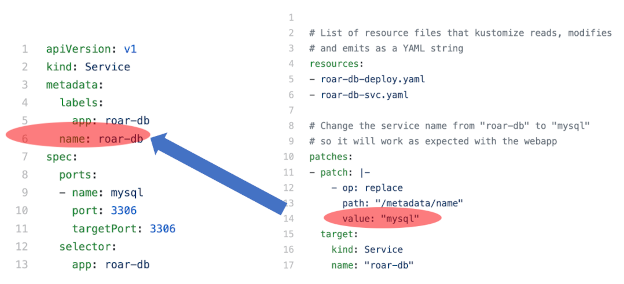

Figures 7a through 7d highlight the patch portion within the kustomization.yaml file associated with the service. Line 12 defines the type of patch, a "replace" in this example. Lines 13 and 14 identify a "location" in the YAML hierarchy to find the value you want to patch and the replacement value to use. Lines 15–17 identify the specific type of item in the K8s resources you wish to change.

Figure 7a: The overall patch block within the kustomization.yaml file (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Figure 7b: The type of patch to apply (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Figure 7c: The location to target in the structure (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Figure 7d: The value to modify (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

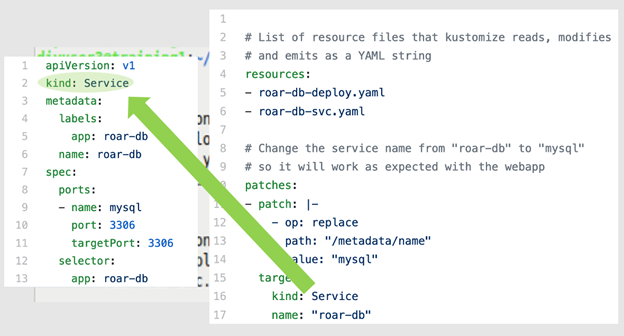

When you execute the kustomize build command against this set of files, Kustomize first locates the K8s resource you're interested in—the service—and then finds the path identified in the patch block (metadata.name.<value>). Then it renders a version of the spec with the value roar-db replaced with mysql. Figures 8a through 8f illustrate this process.

Figures 8a and 8b: Locating the initial named object (kind) (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Figures 8c and 8d: Locating the particular section in the hierarchy (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Figures 8e-8f: Replacing the desired value and rendering the result (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Kustomize supports patching via a "strategic merge patch" (illustrated above) or via JSON patches.

Kustomization hierarchies

The patch scenario example illustrates another useful concept when working with Kustomize: multiple kustomization.yaml files in a project hierarchy. This example project has two subprojects: one for a database and another for a web app.

The database piece has a customization to update the service name with the patch functionality, as described above.

The web piece simply has a file to include the resources.

At the base level, there is a kustomization.yaml file that pulls in resources from both parts of the project and a simple file to create a namespace. It also applies a common label to the different elements.

Generators

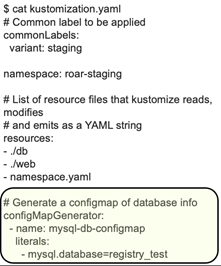

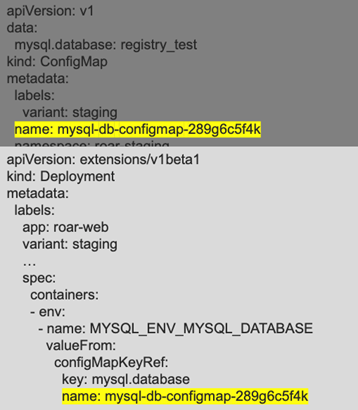

Kustomize also includes "generators" to automatically update related Kubernetes resources when a different resource is updated. A generator establishes a connection between two resources by generating a random identifier and using it as a common suffix on the objects' names.

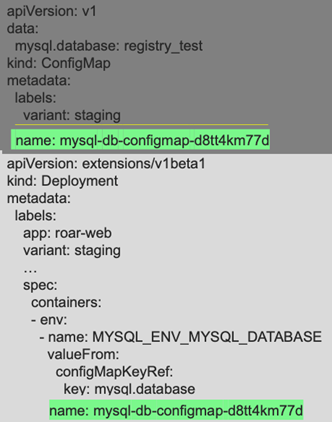

This can be beneficial for configmaps and secrets: If data is changed in them, the corresponding deployment will automatically be regenerated and updated. Figure 9 shows an example specification for a Kustomize generator.

Figure 9a: Example spec for Kustomize generator (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

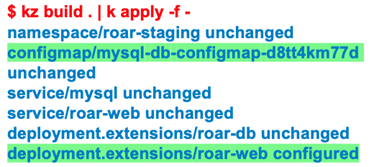

When run through a Kustomize build operation, the new objects produced will have the generated name applied and included in the specs, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 9b: Running kustomize build adds a hash to the references for the generated items (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

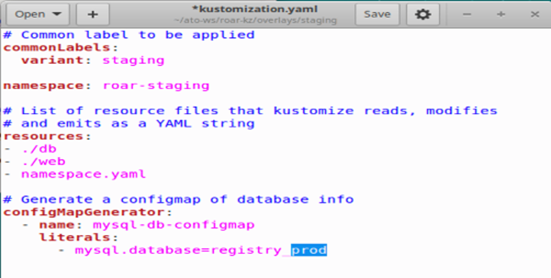

If you then change the configmap associated with the generator (as Figure 11 shows)...

… Kustomize will generate new values that are incorporated into the specs and objects (Figure 12a). Then, if you take the build output and apply it, the deployment will be updated because the associated configmap was updated (Figure 12b).

Figures 9c and 9d: A change in the configMapGenerator spec changes the hash if a build is done again (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Figure 9e: Updates resulting from the hash changes (Brent Laster, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In summary, a kubectl apply operation on the build's results causes the configmap and any dependent items to reference the new hash value of the updated configmap and update them in the cluster.

Kubernetes integration

Kustomize has been integrated into Kubernetes. There are two integration points:

- To view the resources in a directory with a kustomization file, you can run:

$ kubectl kustomize < directory > - To apply those resources, you can use the

-koption onkubectl apply:

$ kubectl apply -k < directory >

If you are using an older version of Kubernetes, it might not have an updated version of Kustomize. In most cases, this isn't a problem unless you need a particular feature or bug fix available in a current version of Kustomize.

Conclusion

Kustomize is another way to facilitate the reuse of Kubernetes manifests. Unlike most other approaches, it leaves the original files intact and generates changed versions on the fly with its build command. The changes to make are defined in a kustomization.yaml file and can include adding various common attributes, making patches on top of original content, or even generating unique identifiers to tie together items like configmaps and deployments.

All in all, Kustomize provides a unique and simple way to deliver variations of Kubernetes manifests once you are comfortable with the setup and function of its various ways to transform files. It is significantly different from the traditional reuse approach taken by Helm, the other main tool for reuse. I'll explore those differences in a future article.

Comments are closed.