There are two kinds of Linux users: the cautious and the adventurous.

On one side is the user who almost reflexively tries out ever new option which hits the scene. They’ve tried handfuls of window managers, dozens of distributions, and every new desktop widget they can find.

On the other side is the user who finds something they like and sticks with it. They tend to like their distribution’s defaults. If they’re passionate about a text editor, it’s whichever one they mastered first.

As a Linux user, both on the server and the desktop, for going on fifteen years now, I am definitely more in the second category than the first. I have a tendency to use what’s presented to me, and I like the fact that this means more often than not I can find thorough documentation and examples of most any use case I can dream up. If I used something non-standard, the switch was carefully researched and often predicated by a strong pitch from someone I trust.

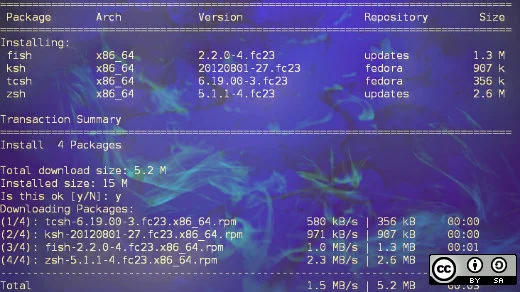

But that doesn’t mean I don’t like to sometimes try and see what I’m missing. So recently, after years of using the bash shell without even giving it a thought, I decided to try out four alternative shells: ksh, tcsh, zsh, and fish. All four were easy installs from my default repositories in Fedora, and they’re likely already packaged for your distribution of choice as well.

Here’s a little bit on each option and why you might choose it to be your next Linux command-line interpreter.

bash

First, let’s take a look back at the familiar. GNU Bash, the Bourne Again Shell, has been the default in pretty much every Linux distribution I’ve used through the years. Originally released in 1989, bash has grown to easily become the most used shell across the Linux world, and it is commonly found in other unix-like operating systems as well.

Bash is a perfectly respectable shell, and as you look for documentation of how to do various things across the Internet, almost invariably you’ll find instructions which assume you are using a bash shell. But bash has some shortcomings, as anyone who has ever written a bash script that’s more than a few lines can attest to. It’s not that you can’t do something, it’s that it’s not always particularly intuitive (or at least elegant) to read and write. For some examples, see this list of common bash pitfalls.

That said, bash is probably here to stay for at least the near future, with its enormous install base and legions of both casual and professional system administrators who are already attuned to its usage, and quirks. The bash project is available under a GPLv3 license.

ksh

KornShell, also known by its command invocation, ksh, is an alternative shell that grew out of Bell Labs in the 1980s, written by David Korn. While originally proprietary software, later versions were released under the Eclipse Public License.

Proponents of ksh list a number of ways in which they feel it is superior, including having a better loop syntax, cleaner exit codes from pipes, an easier way to repeat commands, and associative arrays. It's also capable of emulating many of the behaviors of vi or emacs, so if you are very partial to a text editor, it may be worth giving a try. Overall, I found it to be very similar to bash for basic input, although for advanced scripting it would surely be a different experience.

tcsh

Tcsh is a derivative of csh, the Berkely Unix C shell, and sports a very long lineage back to the early days of Unix and computing itself.

The big selling point for tcsh is its scripting language, which should look very familiar to anyone who has programmed in C. Tcsh's scripting is loved by some and hated by others. But it has other features as well, including adding arguments to aliases, and various defaults that might appeal to your preferences, including the way autocompletion with tab and history tab completion work.

You can find tcsh under a BSD license.

zsh

Zsh is another shell which has similarities to bash and ksh. Originating in the early 90s, zsh sports a number of useful features, including spelling correction, theming, namable directory shortcuts, sharing your command history across multiple terminals, and various other slight tweaks from the original Bourne shell.

The code and binaries for zsh can be distributed under an MIT-like license, though portions are under the GPL; check the actual license for details.

fish

I knew I was going to like the Friendly Interactive Shell, fish, when I visited the website and found it described tongue-in-cheek with "Finally, a command line shell for the 90s"—fish was written in 2005.

The authors of fish offer a number of reasons to make the switch, all invoking a bit of humor and poking a bit of fun at shells that don't quite live up. Features include autosuggestions ("Watch out, Netscape Navigator 4.0"), support of the "astonishing" 256 color palette of VGA, but some actually quite helpful features as well including command completion based on the man pages on your machine, clean scripting, and a web-based configuration.

Fish is licensed primarily unde the GPL version 2 but with portions under other licenses; check the repository for complete information.

Looking for a more detailed rundown on the precise differences between each option? This site ought to help you out.

So where did I land? Well, ultimately, I’m probably going back to bash, because the differences were subtle enough that someone who mostly used the command line interactively as opposed to writing advanced scripts really wouldn't benefit much from the switch, and I'm already pretty comfortable in bash.

But I’m glad I decided to come out of my shell (ha!) and try some new options. And I know there are many, many others out there. Which shells have you tried, and which one do you prefer? Let us know in the comments!

6 Comments