After a decade-long battle, terms of a settlement agreement were finally reached last week between the European Commission and Microsoft regarding anticompetitiveness. The official settlement is a win for European consumers, but the simultaneous Public Undertaking on Interoperability issued by the company leaves much to be desired for the open source community.

The official settlement is an agreement regarding the bundling of Windows and the Internet Explorer browser, which the Commission had argued gave Microsoft an unfair advantage in the web browser market.

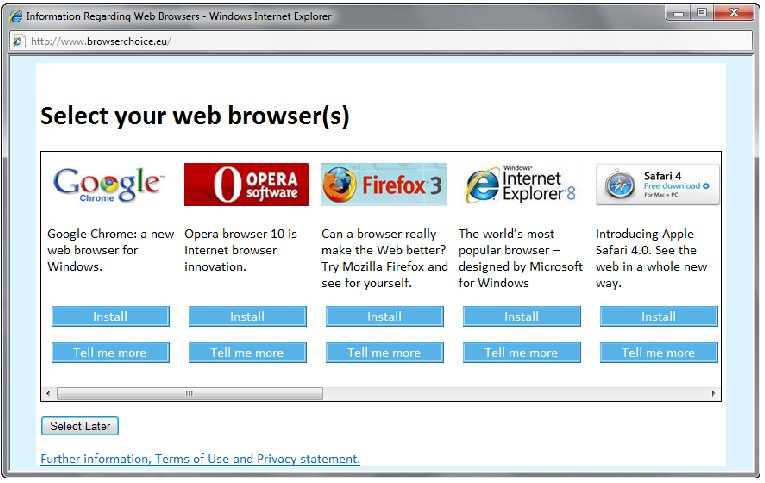

European users of Microsoft Windows will soon see a pop-up ballot screen, like the one pictured, allowing them to choose one of twelve browsers to use: Internet Explorer, Safari, Chrome, Firefox, Opera, AOL, Maxthon, K-Meleon, Flock, Avant Browser, Sleipnir and Slim Browser. According to the Commission, “This should ensure competition on the merits and allow consumers to benefit from technical developments and innovation both on the web browser market and on related markets, such as web-based applications.”

European users of Microsoft Windows will soon see a pop-up ballot screen, like the one pictured, allowing them to choose one of twelve browsers to use: Internet Explorer, Safari, Chrome, Firefox, Opera, AOL, Maxthon, K-Meleon, Flock, Avant Browser, Sleipnir and Slim Browser. According to the Commission, “This should ensure competition on the merits and allow consumers to benefit from technical developments and innovation both on the web browser market and on related markets, such as web-based applications.”

You can read the case documents on the Commission’s website, and a good synopsis of the issues about the web browser and effects of the settlement from the AP writeup.

At the same time, Microsoft published its revised Public Undertaking of Interoperability, which the Commission’s press release is careful to point is not a part of the settlement, although the government “welcomes this initiative to improve interoperability.” The Public Undertaking says the company will provide developers, including those in the open source community, access to technical documentation to products such as Windows, Windows Server, Office, Exchange and SharePoint. It sounds very positive for open source developers, until you see that the Patent Pledge redefines open source to exclude commercial applications.

“An ‘open source project’ is a software development project the resulting source code of which is freely distributed, modified, or copied pursuant to an open source license and is not commercially distributed by its participants. If You engage in the commercial distribution or importation of software derived from an open source project or if You make or use such software outside the scope of creating such software code, You do not benefit from this promise for such distribution or for these other activities.” [note: emphasis mine]

First, are we really back here again - arguing whether free/open source software can be sold for profit? Perhaps we should revisit the Open Source Definition maintained by the Open Source Initiative, which pretty clearly states that you can sell the software if you want. Or not. It’s your choice.

This Patent Pledge definition takes away that choice by attempting to exclude commercial applications. Doesn’t that sound “anticompetitive” to you? Isn’t it ironic that this is being promoted to coincide with the company’s settlement of an anticompetition suit? Of course, this isn’t new. You can read more about it at Groklaw.

But, before your blood starts to boil, the key to remember here is that progress is slowly being made in the government space. Although the undertaking isn’t part of the settlement with the Commission, the government body noted that it “will carefully monitor the impact of this undertaking on the market and take its findings into account in the pending antitrust investigation regarding interoperability.” With that and the official settlement, the European Commission has sent a strong message to the tech industry that it will not tolerate practices that lead to vendor lock-in. The government body instead stood for consumers who should have freedom of choice in the products they want to use. Kudos.

3 Comments