"Community" is a defining characteristic of open organizations. A community could be many things—a "team," a "group," a "department," or a "task force," for example. What makes any of these groups a true community is two distinct factors: a well-defined purpose and clear investment in or value of that purpose.

How does a person balance a community's values with his or her own, personal values? How does that person negotiate this relationship when setting goals? Answers to these questions will expose and speak to that person's character.

So leaders should be asking themselves: What is the character of your open organization community and its members? In what ways must community members balance personal goals with communal ones—and what outcomes does that drive?

One book that I recently read to help me explore those questions is The H Factor of Personality: Why Some People Are Manipulative, Self-Entitled, Materialistic, and Exploitive—And Why It Matters to Everyone, by Kibeom Lee and Michael C. Ashton. In this review I'll explain what the book has to say about character—and specifically what the authors call "The H Factor" (for "honesty and humility"). In a second review, I'll discuss the other five factors that influence open organization communities and those factors' relationship to this H Factor.

The H Factor

Psychologists typically subscribe to a five-factor model of personality. That model holds that personal characteristics cluster into five core traits:

- Emotionality

- eXtraversion

- Agreeableness (versus Anger)

- Conscientiousness

- Openness to experience

These factors help summarize a wide range of behaviors and thought processes. But according to authors Lee and Ashton, a sixth dimension is equally as important: honesty and humility, the "H Factor." It sums up a person's willingness to exploit or avoid exploiting others. The authors describe it like this:

Persons with very high scores on the Honesty-Humility (H) scale avoid manipulating others for personal gain, feel little temptation to break rules, are uninterested in lavish wealth and luxuries, and feel no special entitlement to elevated social status. Conversely, persons with very low scores on this scale will flatter others to get what they want, are inclined to break rules for personal profit, are motivated by material gain and feel a strong sense of self-importance.

To understand the dichotomy of personalities here, try this thought experiment: Imagine you are in a combat military company, and a situation arises in which you can save yourself—but the whole company, say 20 people, will die. But if you sacrifice yourself, you will save the rest of the entire company. Which would you choose?

The extremely "high H" person would sacrifice himself or herself without question. The extremely "low H" person would sacrifice the whole company to save himself or herself without question.

Most of us operate in between these two extremes. We all want to get something from the communities in which we participate. We also desire to provide something to the group as well. The exact point where we are between those two thoughts, will determine our weighted level of "H."

Developing H Factor

H Factor speaks to the ways people prioritize either their own goals or the goals of the community—and it's extremely important in open organizations, where contributors are investing in projects and activities for different reasons and with different goals. Leaders should be paying attention to the value contributors are providing, what they're gaining from their contribution, and how they feel when they are not very helpful to the organization. And they must be careful not to exploit those contributors. In short: They need a well-tuned H Factor.

Consider the "degree to which a person takes others' perspectives into account and feels responsibility for not harming them," or what some psychologists call "guilt-proneness." According to an article in Psychology Today, guilt-proneness "steers people away from relationships in which they might get a free ride and into more equitable relationships." They don't want to take advantage of others, and feel guilty when they do. This is an extremely important point when it comes to identifying a person's level of "H" and the intent behind his or her behavior.

Traditional models of personality also stress that "having the desire to do good is necessary, but it isn't sufficient." One must also have the skills and ability to do good and desire to avoid doing harm. Here's where the ability to consider future consequences becomes important. What people do will either make them feel proud or guilty. People with a high "H factor," some argue, "actually see the world differently from those who lack it"; they look through "a moral lens" and view their actions with an eye toward how what they do could impact others.

A person's character typically doesn't show itself quickly; it only reveals itself in time. Character is something we can only infer through behavior, and moral character is something that shows itself only when some kind of difficult choice is required. Most everyday circumstances do not present a test of loyalty, for example, or offer an opening for a display of courage. On the other hand, there may be far more everyday opportunities for showing kindness and compassion.

But here's where it gets most interesting: Character influences how people enter into situations and exit out of others. We can spot this in our open organizations:

- Does a person recognize the discomfort of the group and discuss it, or not?

- Will the person try to remedy the discomfort or not get involved?

- Will the person offer support or encouragement to people involved?

- Is the person offering an apology for not being helpful enough? How sincere or strong are those apologies?

Building a community's H Factor

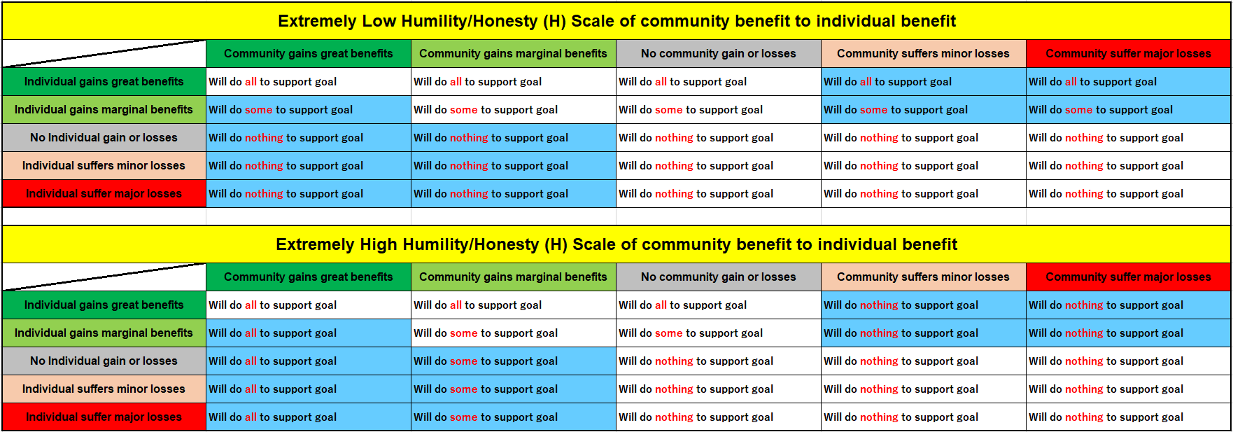

Lee and Ashton chart "high H" and "low H" personalities this way.

|

Honesty-Humility (H) |

|

|

High |

Low |

|

|

Table reproduced from The H Factor (pp. 20-21)

How can we build our communities to best take advantage of the mix of H Factors within them? To help answer that question, I've put together the following chart. Where would you feel guilt for taking too much from the community, or feel taken advantage of by the community? How can (or should) people with varying H Factors work together with a purpose?

Courtesy of Ron McFarland (CC BY-SA); click for larger version

Note the white boxes: the low H people are compatible with the community, as those low H people will gain something themselves by helping to achieve the community's purpose (or both will not support the goal as both individual and community suffers). In the blue area, the low H people will not support the community, even if the community will gain benefits. Also, a low H person will support projects that might be damaging to the community. Therefore, these low H people must be identified and their behavior observed very closely, considering the community's gain and the low H individual's gain.

I'll talk more about this in the second part of this review.

2 Comments