"Change is going to be continual, and today is the slowest day society will ever move."—Tony Fadell

If ever there was an experience that brought the above quotation home for me, it was my experience at the All Things Open conference in Raleigh, NC last October. Thousands of people from all over the world attended the conference, and many (if not most), worked as open source coders and developers. As one of the relatively few educators in attendance, I saw and heard things that were completely foreign to me—terms like as Istio, Stack Overflow, Ubuntu, Sidecar, HyperLedger, and Kubernetes tossed around for days.

I felt like a fish out of water. But in the end, that was the perfect dose of reality I needed to truly understand how open principles can reshape our approach to education.

Not-so-strange attractors

All Things Open attracted me to Raleigh for two reasons, both of which have to do with how our schools must do a better job of creating environments that truly prepare students for a rapidly changing world.

The first is my belief that schools should embrace the ideals of the open source way. The second is that educators have to periodically force themselves out of their relatively isolated worlds of "doing school" in order to get a glimpse of what the world is actually doing.

When I was an engineer for 20 years, I developed a deep sense of the power of an open exchange of ideas, of collaboration, and of the need for rapid prototyping of innovations. Although we didn't call these ideas "open source" at the time, my colleagues and I constantly worked together to identify and solve problems using tools such as Design Thinking so that our businesses remained competitive and met market demands. When I became a science and math teacher at a small public school in rural Appalachia, my goal was to adapt these ideas to my classrooms and to the school at large as a way to blur the lines between a traditional school environment and what routinely happens in the "real world."

Through several years of hard work and many iterations, my fellow teachers and I were eventually able to develop a comprehensive, school-wide project-based learning model, where students worked in collaborative teams on projects that made real connections between required curriculum and community-based applications. Doing so gave these students the ability to develop skills they can use for a lifetime, rather than just on the next test—skills such as problem solving, critical thinking, oral and written communication, perseverance through setbacks, and adapting to changing conditions, as well as how to have routine conversations with adult mentors form the community. Only after reading The Open Organization did I realize that what we had been doing essentially embodied what Jim Whitehurst had described. In our case, of course, we applied open principles to an educational context (that model, called Open Way Learning, is the subject of a book published in December).

As good as this model is in terms of pushing students into a relevant, engaging, and often unpredictable learning environments, it can only go so far if we, as educators who facilitate this type of project-based learning, do not constantly stay abreast of changing technologies and their respective lexicon. Even this unconventional but proven approach will still leave students ill-prepared for a global, innovation economy if we aren't constantly pushing ourselves into areas outside our own comfort zones. My experience at the All Things Open conference was a perfect example. While humbling, it also forced me to confront what I didn't know so that I can learn from it to help the work I do with other teachers and schools.

A critical decision

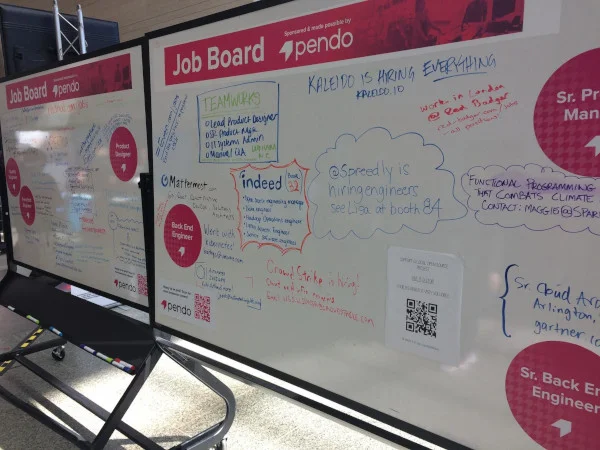

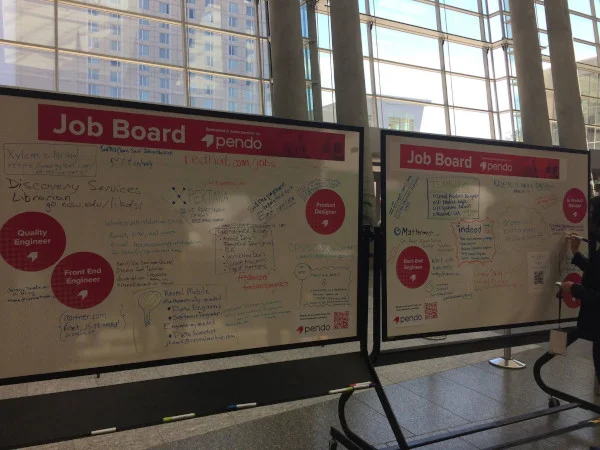

I made this point to others when I shared a picture of the All Things Open job board with dozens of colleagues all over the country. I shared it with the caption: "What did you do in your school today to prepare your students for this reality tomorrow?" The honest answer from many was, unfortunately, "not much." That has to change.

(Images courtesy of Ben Owens, CC BY-SA)

People in organizations everywhere have to make a critical decision: either embrace the rapid pace of change that is a fact of life in our world or face the hard reality of irrelevance. Our systems in education are at this same crossroads—even ones who think of themselves as being innovative. It involves admitting to students, "I don't know, but I'm willing to learn." That's the kind of teaching and learning experience our students deserve.

It can happen, but it will take pioneering educators who are willing to move away from comfortable, back-of-the-book answers to help students as they work on difficult and messy challenges. You may very well be a veritable fish out of water.

4 Comments