Culture matters in open organizations. But "culture" seems like such a large, complicated concept to address. How can we help open organization teams better understand it?

One solution might come from Michele J. Gelfand, author of Rule Makers, Rule Breakers: Tight and Loose Cultures and the Secret Signals That Direct Our Lives. Gelfand organizes all countries and cultures into two very simple groups: those with "tight" cultures and those with "loose" ones. Then she explains the characteristics and social norms of both, offering their relative strengths and weaknesses. By studying both, one might overcome the divisions and conflicts that separate people in and across teams, organizations, and countries.

In this two-part review of Rule Makers, Rule Breakers, I'll explain Gelfand's argument and discuss the ways it's useful to people working in open organizations.

Know your social norms

Gelfand believes that our behavior is very strongly dependent on whether we live in a "tight" or "loose" community culture, because each of these cultures has social norms that differ from the other. These norms—and the strictness with which they are enforced—will determine our behavior in the community. They give us our identity. They help us coordinate with each other. In short, they're the glue that holds communities together.

They also impact our worldviews, the ways we build our environments, and even the processing in our brains. "Countless studies have shown that social norms are critical for uniting communities into cooperative, well-coordinated groups that can accomplish great feats," Gelfand writes. Throughout history, communities have put their citizens through the seemingly craziest of rituals for no other reason than to maintain group cohesion and cooperation. The rituals result in greater bonding, which has kept people alive (particularly in times of hunting, foraging, and warfare).

Social norms include rules we all tend to follow automatically, what Gelfand calls a kind of "normative autopilot." These are things we do without thinking about them—for example, being quiet in libraries, cinemas, elevators, or airplanes. We do these things automatically. "From the outside," Gelfand says, "our social norms often seem bizarre, but from the inside, we take them for granted." She explains that social norms can be codified into regulations and laws ("obey stop signs" and "don't steal"). Others are largely unspoken ("don't stare at people on the train" or "cover your mouth when you sneeze"). And, of course, they vary by context.

The challenge is that most social norms are invisible, and we don't know how much these social norms control us. Without knowing it, we often just follow the groups in our surroundings. This is called "groupthink," in which people will follow along with their identifying group, even if the group is wrong. They don't want to stand out.

Organizations, tight and loose

Gelfand organizes social norms into various groupings. She argues that some norms are characteristic of "tight" cultures, while others are characteristic of "loose" cultures. To do this, Gelfand researched and sampled approximately seven thousand people from more than 30 countries across five continents and with a wide range of occupations, genders, ages, religions, sects, and social classes in order to learn where those communities positioned themselves (and how strongly their social norms were enforced officially and by the communities/neighborhoods in general). Differences between tight and loose cultures vary between nations, within countries (like within the United States and its various regions), within organizations, within social classes and even within households.

Because organizations have cultures, they too have their own social norms (after all, if an organization is unable to coordinate its members and influence their behavior, it won't be able to survive). So organizations can also reflect and instill the "light" or "loose" cultural characteristics Gelfand describes. And if we have a strong ability to identify these differences, we can predict and address conflict more successfully. Then, armed with greater awareness of those social norms, we can put open organization principles to work.

Gelfand describes the difference between tight and loose cultures this way:

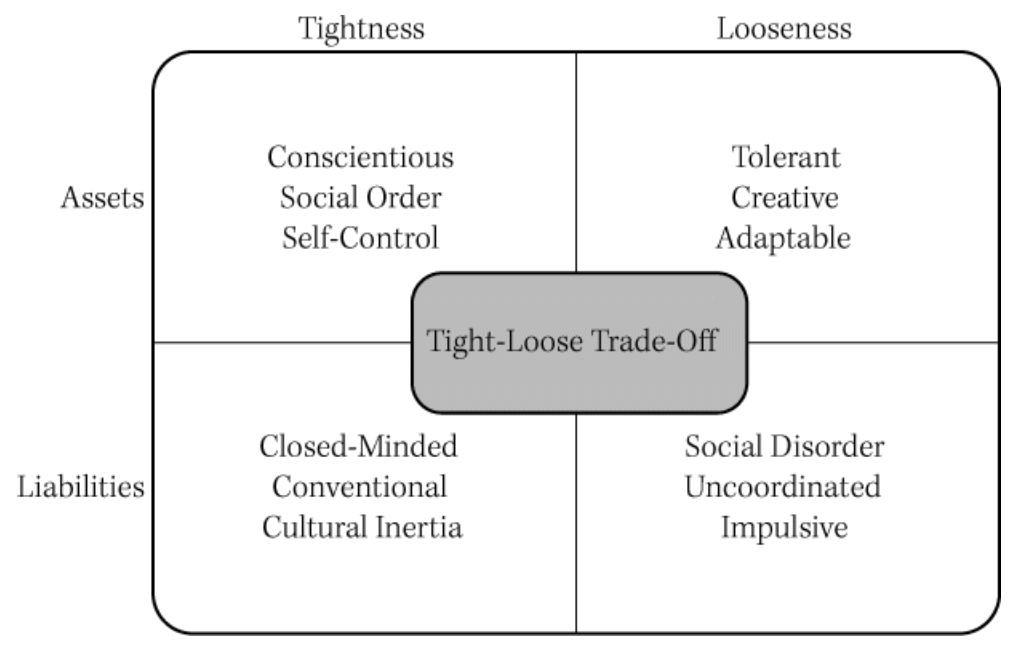

Broadly speaking, loose cultures tend to be open, but they're also much more disorderly. On the flip side, tight cultures have a comforting order and predictability, but they're less tolerant. This is the tight-loose trade-off: advantages in one realm coexist with drawbacks in another.

Tight societies, she concludes, maintain strict social order, synchrony and self-regulation; loose societies take pride in being highly tolerant, creative and open to change.

Although not true in every case, tight and loose cultures generally exhibit some trade-offs; each has its own strengths and weaknesses. See Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Characteristics of tight and loose cultures (from Rule Makers, Rule Breakers, pg. 56)

The work of successfully applying the five open organization principles in these two environments can vary greatly. To be successful, community commitment is vital, and if the social norms are different, the reasons for commitment would be different as well. Organizational leaders must know what the community's values are. Only then can that person adequately inspire others.

In the next part of this review, I'll explain more thoroughly the characteristics of tight and loose cultures, so leaders can get a better sense of how they can put open organization principles to work on their teams.

Comments are closed.