With the recent worldwide pandemic and stay-at-home orders, I have been looking for things to do to replace some of my usual activities. I started to update my home electronics setup and, as part of that, to delve into home automation. Some of my friends use Amazon's Alexa to turn lights on and off in their house, and that is appealing on some level. However, I am a privacy-conscious individual, and I was never really comfortable with devices from Google or Amazon listening to my family all the time (I'll ignore cellphones for the sake of this conversation). I have known about the open source voice assistant Mycroft for about four years, but due to early struggles with the project, I'd never investigated it too closely. The project has come a very long way since I first stumbled across it, and it checks a lot of boxes for me:

- Self-hosted

- Easy onboarding (via Python)

- Open source

- Privacy-conscious

- Interactive chat channel

In the first article in this series, I introduced Mycroft, and in the second article, I touched upon the concept of skills in artificial intelligence. In its most basic form, a skill is a block of code that is executed to achieve the result desired for an intent. Intents attempt to determine what you want, and a skill is the way Mycroft responds. If you can think of an outcome, there is probably a way to create a skill that makes it happen.

At their heart, Mycroft skills are just Python programs. Generically, they have three or four sections:

- The import section is where you load any Python modules required to accomplish the task.

- An optional function section contains snippets of code that are defined outside of the main class section.

- The class section is where all the magic happens. A class should always take the

MycroftSkillas an argument. - The create_skill() section is what Mycroft uses to load your skill.

When I write a skill, I often start by writing a standard Python file to ensure my code does what I think it does. I do this mainly because the workflow that I am used to, including debugging tools, exists outside of the Mycroft ecosystem. Therefore, if I need to step through my code, I find it much more familiar to use my IDE (PyCharm) and its built-in tools, but this is a personal preference.

All the code for this project can be found in my GitLab repo.

About intent parsers

The skill in this project uses both the Padatious and Adapt intent parsers, which I described in my previous article. Why? First of all, this tutorial is meant to provide a concrete example of some of the features you might want to consider using in your own skill. Second, Padatious intents are very straightforward but do not support regular expressions, while Adapt puts regex to good use. Also, Padatious intents aren't context-aware, which means that, while you could prompt the user for a response and then parse it following some decision-tree matrix, you might be better off using the Adapt intent parser with Mycroft's built-in context handler. Note that, by default, Mycroft assumes you are using the Padatious intent handler. Finally, it's good to note that Adapt is a keyword intent parser. This can make complex parsing cumbersome if you are not a regex ninja. (I am not.)

Implement the 3 T's

Before you start writing a skill, consider the 3 T's: Think things through! Similar to when you're writing an outline for an essay, when you're starting to develop a skill, write down what you want your skill to do.

This tutorial will step through writing a Mycroft skill to add items to the OurGroceries app (which I am not affiliated with). In truth, this skill was my wife's idea. She wanted an application she could use on her phone to manage her shopping lists. We tried almost a dozen apps to try to meet our individual needs—I needed an API or a way to easily interact with the backend, and she had a giant list of criteria, one of the most important was that it is easy to use from her phone. After she made her list of Must-haves, Nice-to-haves, and Wish-list items, we settled on OurGroceries. It does not have an API, but it does have a way to interact with it through JSON. There is even a handy library called py-our-groceries in PyPI (which I have contributed some small amount to).

Once I had an objective and a target platform, I started to outline what the skill needed to do:

- Login/authenticate

- Get a list of the current grocery lists

- Add item to a specific grocery list

- Add item to a category under a specific list

- Add a category (since OurGroceries allows items to be placed in categories)

With this in mind, I started to sketch out the required Python. Here is what I came up with.

Create the Python sketch

By reading the examples for the py-our-groceries library, I figured out I needed to import just two things: asyncio and ourgroceries.

Simple enough. Next, I knew that I needed to authenticate with username and password, and I knew what tasks the program needed to do. So my sketch ended up looking like this:

import asyncio

from ourgroceries import OurGroceries

import datetime

import json

import os

USERNAME = ""

PASSWORD = ""

OG = OurGroceries(USERNAME, PASSWORD)

def fetch_list_and_categories():

pass

def return_category_id():

pass

def add_to_my_list():

pass

def add_category():

passI won't go into the full details of what makes this sketch tick, as that is outside the scope of this series. However, if you want, you can view the working outline in its entirety.

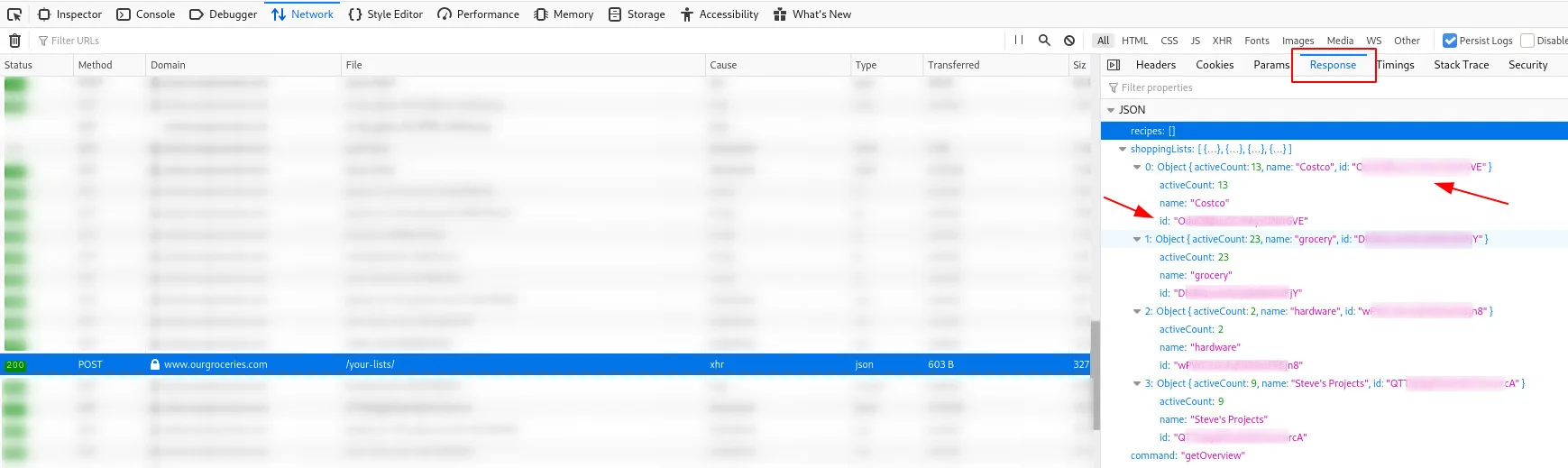

Before you can begin programming, you need to have your username, password, and a list ID. The username and password are obvious. The list ID can be retrieved from the URL after clicking on the link, or more programmatically, you can use the Developer Tools for your browser of choice and inspect the objects. Here is what the Developer Tools looks like in Firefox:

Once you have a list ID, log into OurGroceries and get a cookie. To do this, create an OurGroceries object and then pass it into asyncio. While you are at it, you might as well define your list ID, as well:

OG = OurGroceries(USERNAME, PASSWORD)

asyncio.run(OG.login())

MY_LIST_ID = "a1kD7kvcMPnzr9del8XMFc"For the purposes of this project, you need to define two object types to help organize your code: groceries and categories. The fetch_list_and_categories method is pretty straightforward:

def fetch_list_and_categories(object_type=None):

if object_type == "groceries":

list_to_return = asyncio.run(OG.get_list_items(list_id=MY_LIST_ID))

elif object_type == "categories":

list_to_return = asyncio.run(OG.get_category_items())

else:

list_to_return = None

return (list_to_return)OurGroceries allows you to add more than one category or item with the same name. For example, if you already have "Meat" on your list and you add it again, you will see a category called "Meat (2)" (this number increments whenever you create a category with the same name). For us, this was undesirable behavior. We also wanted to avoid duplication as much as possible, so I made a rudimentary attempt at detecting plurals; for example, my code checks for both "Meat" and "Meats." I am sure there is a more intelligent way of performing these checks, but this example highlights some of the things you may want to think about as you progress. For brevity, I will omit these checks, so the return_category_id method looks something like this:

def return_category_id(category_to_search_for, all_categories):

category_to_search_for_lower = category_to_search_for.lower()

category_id = None

if len(all_categories['list']['items']) is not 0:

for category_heading in all_categories['list']['items']:

# Split the heading because if there is already a duplicate it

# presents as "{{item}} (2)"

category_heading_lowered = category_heading['value'].lower().split()[0]

if category_to_search_for_lower == category_heading_lowered:

category_id = category_heading['id']

break

return(category_id)To add an item to the list, you want to:

- Check that the item does not already exist

- Obtain the category ID

- Add the item to the list under a specific category (if specified)

The add_to_my_list method ends up something like this:

def add_to_my_list(full_list, item_name, all_categories, category="uncategorized"):

# check to make sure the object doesn't exist

# The groceries live in my_full_list['list']['items']

# Start with the assumption that the food does not exist

food_exists = False

toggle_crossed_off = False

category_lowered = category.lower()

for food_item in full_list['list']['items']:

if item_name in food_item['value']:

print("Already exists")

food_exists = True

if not food_exists:

category_id = return_category_id(category_lowered, all_categories)

asyncio.run(OG.add_item_to_list(MY_LIST_ID, item_name, category_id))

print("Added item")Finally, add_category runs the asyncio command to create a category if it does not already exist:

def add_category(category_name, all_categories):

category_id = return_category_id(category_name, all_categories)

if category_id is None:

asyncio.run(OG.create_category(category_name))

refresh_lists()

print("Added Category")

else:

print("Category already exists")You should now be able to test your sketch to make sure everything in each function works. Once you are satisfied with the sketch, you can move on to thinking about how to implement it in a Mycroft skill.

Plan the Mycroft skill

You can apply the same principles you used to sketch out your Python to developing a Mycroft skill. The official documentation recommends using an interactive helper program called the Mycroft Skills Kit to set up a skill. mycroft-msk create asks you to:

- Name your skill

- Enter some phrases commonly used to trigger your skill

- Identify what dialog Mycroft should respond with

- Create a skill description

- Pick an icon from

fontawesome.com/cheatsheet - Pick a color from

mycroft.ai/colorsorcolor-hex.com - Define a category (or categories) where the skill belongs

- Specify the code's license

- State whether the skill will have dependencies

- Indicate whether you want to create a GitHub repo

Here is a demonstration of how mycroft-msk create works:

(Steve Ovens, CC BY-SA 4.0)

After you answer these questions, Mycroft creates the following structure under mycroft-core/skills/<skill name>:

├── __init__.py

├── locale

│ └── en-us

│ ├── ourgroceries.dialog

│ └── ourgroceries.intent

├── __pycache__

│ └── __init__.cpython-35.pyc

├── README.md

├── settings.json

└── settingsmeta.yamlYou can ignore most of these files for now. I prefer to make sure my code is working before trying to get into Mycroft-specific troubleshooting. This way, if things go wrong later, you know it is related to how your Mycroft skill is constructed and not the code itself. As with the Python sketch, take a look at the outline that Mycroft created in __init__.py.

All Mycroft skills should have an __init__.py. By convention, all code should go in this file, although if you are a skilled Python developer and know how this file works, you could choose to break your code out.

Inside the file Mycroft created, you can see:

from mycroft import MycroftSkill, intent_file_handler

class OurGroceries(MycroftSkill):

def __init__(self):

MycroftSkill.__init__(self)

@intent_file_handler('ourgroceries.intent')

def handle_test(self, message):

self.speak_dialog('ourgroceries')

def create_skill():

return OurGroceries()In theory, this code will execute based on the trigger(s) you create during the msk create process. Mycroft first tries to find a file with the .dialog file extension that matches the argument passed to selfspeak_dialog(). In the example above, Mycroft will look for a file called ourgroceries.dialog and then say one of the phrases it finds there. Failing that, it will say the name of the file. I'll get more into this in a follow-up article about responses. If you want to try this process, feel free to explore the various input and output phrases you can come up with during skill creation.

While the script is a great starting point, I prefer to think through the __init__.py on my own. As mentioned earlier, this skill will use both the Adapt and Padatious intent handlers, and I also want to demonstrate conversational context handling (which I'll get deeper into in the next article). So start by importing them:

from mycroft import intent_file_handler, MycroftSkill, intent_handler

from mycroft.skills.context import adds_context, removes_contextIn case you are wondering, the order you specify your import statements does not matter in Python. After the imports are done, look at the class structure. If you want to learn more about classes and their uses, Real Python has a great primer on the subject.

As above, start by mocking up your code with its intended functionality. This section uses the same goals as the Python sketch, so go ahead and plug some of that in, this time adding some comments to help guide you:

class OurGroceriesSkill(MycroftSkill):

def __init__(self):

MycroftSkill.__init__(self)

# Mycroft should call this function directly when the user

# asks to create a new item

def create_item_on_list(self, message):

pass

# Mycroft should also call this function directly

def create_shopping_list(self, message):

pass

# This is not called directly, but instead should be triggered

# as part of context aware decisions

def handle_dont_create_anyways_context(self):

pass

# This function is also part of the context aware decision tree

def handle_create_anyways_context(self):

pass

def stop(self):

passThe __init__ and initialize methods

A skill has a few "special" functions that you should know about. The __init__(self) method is called when the skill is first instantiated. In Python IDEs, variables that are declared outside of the __init__ section will often cause warnings. Therefore, they are often used to declare variables or perform setup actions. However, while you can declare variables intended to match the skills settings file (more on this later), you cannot use the Mycroft methods (such as self.settings.get) to retrieve the values. It is generally not appropriate to attempt to make connections to the outside world from __init__. Also, the __init__ function is considered optional within Mycroft. Most skills opt to have one, and it is considered the "Pythonic" way of doing things.

The initialize method is called after the skill is fully constructed and registered with the system. It is used to perform any final setup for the skill, including accessing skill settings. It is optional, however, and I opted to create a function that gets the authentication information. I called it _create_initial_grocery_connection, if you are curious and want to look ahead. I will revisit these two special functions in the next article when I start walking through creating the skill code.

Finally, there is a special function called stop(), which I didn't use. The stop method is called anytime a user says, "stop." If you have a long-running process or audio playback, this method is useful.

Wrapping up

So you now have the outline of what you want to accomplish. This will definitely grow over time. As you develop your skill, you will discover new functionality that your skill will require to work optimally.

Next time, I will talk about the types of intents you will use, how to set them up, and how to deal with regular expressions. I'll also explore the idea of conversational contexts, which are used for getting feedback from the user.

Do you have any comments, questions, or concerns? Leave a comment, visit me on Twitter @linuxovens, or stop by Mycroft skills chat channels.

Comments are closed.