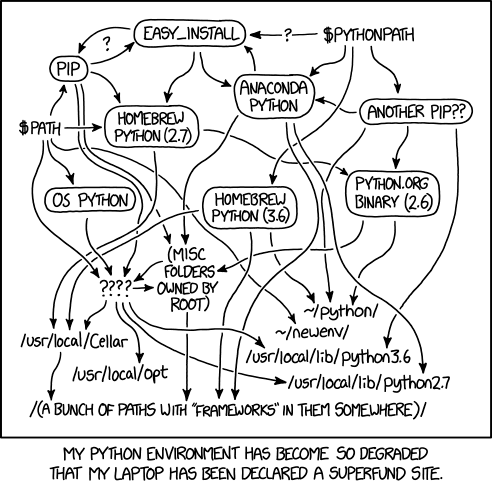

Python is a wonderful general-purpose programming language, often taught as a first programming language. Twenty years in, multiple books written, and it remains my language of choice. While the language is often said to be straight-forward, configuring Python for development has not been described as such (as documented by xkcd).

A complex Python environment: xkcd

There are many ways to use Python in your day-to-day life. I will explain how I use the Python ecosystem tools, and I will be honest where I am still looking for alternatives.

Use pyenv to manage Python versions

The best way I have found to get a Python version working on your machine is pyenv. This software will work on Linux, Mac OS X, and WSL2: the three "UNIX-like" environments that I usually care about.

Installing pyenv itself can be a little tricky at times. One way is to use the dedicated pyenv installer, which uses a curl | bash method to bootstrap (see the instructions for more details).

If you're on a Mac (or another system where you run Homebrew), you can follow instructions on how to install and use pyenv here.

Once you install and set up pyenv per the directions, you can use pyenv global to set a "default Python" version. In general, you will want to select your "favorite" version. This will usually be the latest stable, but other considerations can change that.

Make virtual environments simpler with virtualenvwrapper

One advantage of using pyenv to install Python is that all subsequent Python interpreter installations you care about are owned by you instead of the operating system you use.

Though installing things inside Python itself is usually not the best option, there is one exception: in your "favorite" Python chosen above, install and configure virtualenvwrapper. This gives you the ability to create and switch to virtual environments at a moment's notice.

I walk through exactly how to install and use virtualenvwrapper in this article.

Here is where I recommend a unique workflow. There is one virtual environment that you will want to make so that you can reuse it a lot—runner. In this environment, install your favorite runner; that is, software that you will regularly use to run other software. As of today, my preference is tox.

Use tox as a Python runner

tox is a great tool to automate your test runs of Python. In each Python environment, I create a tox.ini file. Whatever system I use for continuous integration will run it, and I can run the same locally with virtualenvwrapper's workon syntax described in the article above:

$ workon runner

$ toxThe reason this workflow is important is that I test my code against multiple versions of Python and multiple versions of the library dependencies. That means there are going to be multiple environments in the tox runner. Some will try running against the latest dependencies. Some will try running against frozen dependencies (more on that next), and I might also generate those locally with pip-compile.

Side note: I am currently looking at nox as a replacement for tox. The reasons are beyond the scope of this article, but it's worth taking a look at.

Use pip-compile for Python dependency management

Python is a dynamic programming language, which means it loads its dependencies on every execution of the code. Understanding exactly what version of each dependency is running could mean the difference between smoothly running code and an unexpected crash. That means we have to think about dependency management tooling.

For each new project, I include a requirements.in file that is (usually) only the following:

.Yes, that's right. A single line with a single dot. I document "loose" dependencies, such as Twisted>=17.5 in the setup.pyfile. That is in contrast to exact dependencies like Twisted==18.1, which make it harder to upgrade to new versions of the library when you need a feature or a bug fix.

The . means "current directory," which uses the current directory's setup.py as the source for dependencies.

This means that using pip-compile requirements.in > requirements.txt will create a frozen dependencies file. You can use this dependencies file either in a virtual environment created by virtualenvwrapper or in tox.ini.

Sometimes it is useful to have requirements-dev.txt, generated from requirements-dev.in (contents: .[dev]) or requirements-test.txt, generated from requirements-test.in (contents: .[test]).

I am looking to see if pip-compile should be replaced in this flow by dephell. The dephell tool has a bunch of interesting things about it, like the use of asynchronous HTTP requests to speak dependency downloads.

Conclusion

Python is as powerful as it is pleasing on the eyes. In order to write that code, I lean on a particular toolchain that has worked well for me. The tools pyenv, virtualenvwrapper, tox, and pip-compile are all separate. However, they each have their own role, with no overlaps, and together, they deliver a powerful Python workflow.

1 Comment