A software project's design is a consequence of the time it was written. As circumstances change, it's wise to take a step back and consider whether old ideas still make for a good design. If not, you risk missing out on enhancements, simplifications, new degrees of freedom, or even a project's very survival.

This is relevant advice for .NET developers whose dependencies are subject to constant updates or are preparing for .NET 5. The Fixie project confronted this reality as we flexed to outside circumstances during the early adoption phase of .NET Core. Fixie is an open source .NET test framework similar to NUnit and xUnit with an emphasis on developer ergonomics and customization. It was developed before .NET Core and has gone through a few major design overhauls in response to platform updates.

The problem: Reliable assembly loading

A .NET test project tends to feel a lot like a library: a bunch of classes with no visible entry point. The assumption is that a test runner, like Fixie's Visual Studio Test Explorer plugin, will load your test assembly, use reflection to find all the tests within it, and invoke the tests to collect results. Unlike a regular library, test projects share some similarities with regular console applications:

- The test project's dependencies should be naturally loadable, as with any executable, from their own build output folder.

- When running multiple test projects, the loaded assemblies for test project A should be separate from the loaded assemblies for test project B.

- When the system under test relies on an App.config file, it should use the one local to the test project while the tests are running.

I'll call these behaviors the Big Three. The Big Three are so natural that you rarely find a need to even say them. A test project should resemble a console executable: It should be able to have dependencies, it should not conflict with the assemblies loaded for another project, and each project should respect its own dedicated config file. We take this all for granted. The sky is blue, water is wet, and the Big Three must be honored as tests run.

Fixie v1: Designing for the Big Three

The Big Three pose a huge problem for .NET test frameworks: the primary running process, such as Visual Studio Test Explorer, is nowhere near the test project's build output folder. The most natural attempt to load a test project and run it will fail all of the Big Three.

Early alpha builds of Fixie were naive about assembly loading: The test runner .exe would load a test project and run simple tests, but it would fail as soon as a test tried to run code in another assembly—like the application being tested. By default, it searched for assemblies near the test runner, nowhere near the test project's build output folder.

Once we resolved that, using that test runner to run more than one test project would result in conflicts at runtime, such as when each test project referenced different versions of the same library.

And when we resolved that, the test runner would fail to look in the right config files, mistakenly thinking the test runner's config file was the one to use.

In the days of the regular old .NET Framework, the solution to the Big Three came in the form of AppDomains. AppDomains are a fairly old and now-deprecated technology. Fixie v1 was developed when this was the primary solution, with no deprecation in sight, to the Big Three. Under those circumstances, using AppDomains to solve the Big Three was the ideal design, though it was a bit frustrating to work with them. In short, they let a single test runner carve out little pockets of loaded assemblies with rigid communication boundaries between them.

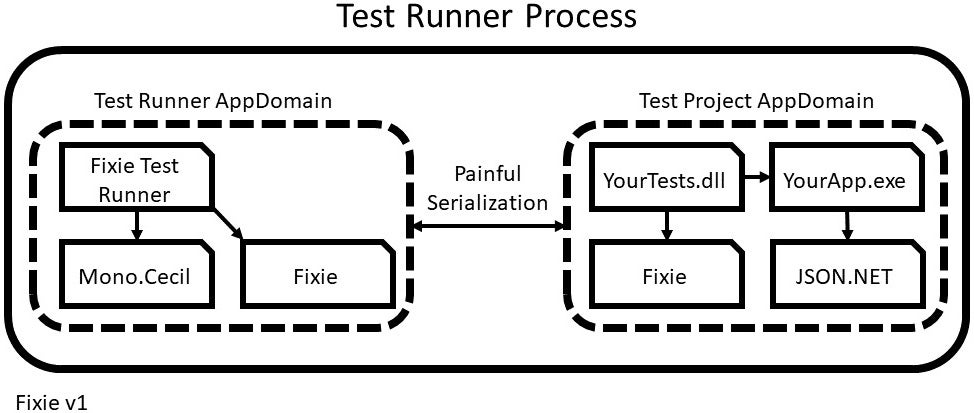

The Test Explorer plugin and its own dependencies (like Mono.Cecil) live in one AppDomain. The test assembly and its dependencies live in a second AppDomain. A painful serialization boundary allows requests to cross the chasm with no risk of mixing the loaded assemblies.

AppDomains let you identify each test project's build output folder as the home of that test project's config file and dependencies. You could successfully load a test project's folder into the test runner process, call into it, and get test results while meeting the Big Three requirements.

And then .NET Core came along. Suddenly, AppDomains were an old and deprecated concept that simply would not continue to exist in the .NET Core world.

Circumstances had changed with a vengeance.

Fixie v2: Adapting to the .NET Core crisis

At first, this seemed like the end of the Fixie project. The entire design depended on AppDomains, and if this newfangled .NET Core thing survived, Fixie would have no answer to the Big Three. Despair. Close up shop. Delete the repository.

In these moments of despair, we were making a classic software development mistake: confusing the solution with the requirements. The actual requirements (the Big Three) had not changed. The circumstances around the design had changed: AppDomains were no longer available. When people make the mistake of confusing their solution with their requirements, they may double down, grip their steering wheel tighter, and just flail around while they try to force their solution to continue working.

Instead, we needed to recognize the plain truth: we had familiar requirements, but new circumstances, and it was time to throw out the old design for something new that met the same requirements under the new circumstances. Once we gave ourselves permission to go back to the drawing board, the solution was clear:

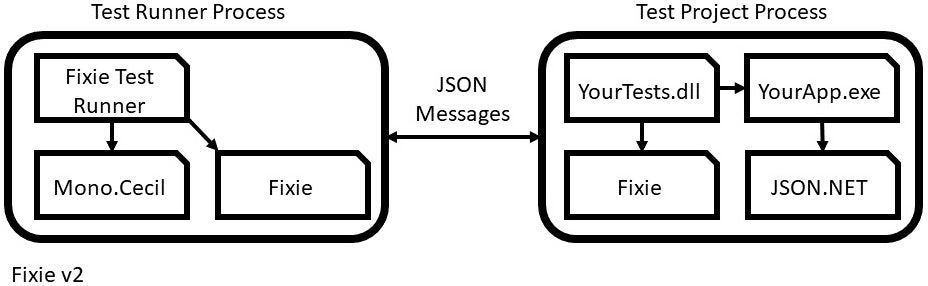

The Big Three let your "library" test project feel like a console application. So, what if your test project was a console application?

A console application already has meaningful notions of loading dependencies from the right folder, distinct from the dependencies of another application, while respecting its own config file. The test runner is no longer the only process in the mix. Instead, the test runner's job is to start the test project as a process of its own and communicate with it to collect results. We traded away AppDomains for interprocess communication, resulting in a new design that met all the original requirements while also working in the context of .NET Framework and .NET Core projects.

This design kept the project alive and allowed us to serve both platforms during those shaky years when it wasn't certain which platform would survive in the long run. However, maintaining support for two worlds became increasingly painful, especially in keeping the Visual Studio Test Explorer plugin alive through every minor Visual Studio release. Every minor Fixie release involved a huge matrix of use cases to do regression testing, and every new little bump in the road brought innovation to a halt.

On top of that, Microsoft was starting to show clear signs that it was abandoning the .NET Framework: the old Framework no longer kept up with advances in .NET Standard, ASP.NET, or C#. The .NET Framework would exist but would quickly fall by the wayside.

Circumstances had changed again.

Fixie v3: Embracing One .NET

Fixie v3 is a work in progress that we intend to release shortly after .NET 5 arrives. .NET 5 is the resolution to the .NET Framework vs. .NET Core development lines, arriving at One .NET. Instead of fighting it, we're following Microsoft's evolution: Fixie v3 will no longer run on the .NET Framework. Removing .NET Framework support allowed us to remove a lot of old, slow implementation details and dramatically simplified the regression testing scenarios we had to consider for reach release. It also allowed us to reconsider our design.

The Big Three requirements changed only slightly: .NET Core does away with the notion of an App.config file closely tied to your executable, instead relying on a more convention-based configuration. All of Fixie's assembly-loading requirements remained. More importantly, the circumstances around the design changed in a fundamental way: we were no longer limited to using types available in both .NET Framework and .NET Core.

By promising less with the removal of .NET Framework support, we gained new degrees of freedom to modernize the system.

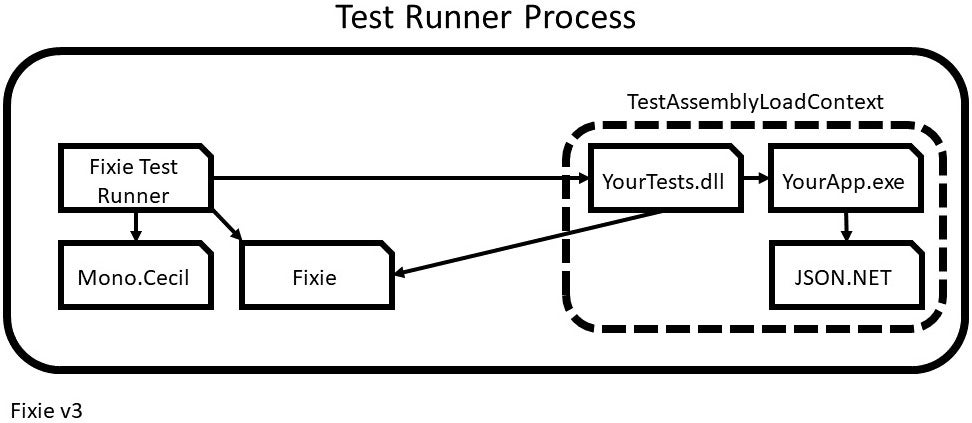

.NET's AssemblyLoadContext is a distant cousin of AppDomains. It's not available to the .NET Framework, so it hadn't been an option for us before. AssemblyLoadContext lets you set up a dedicated loading area for an assembly and its own dependencies without polluting the surrounding process and without being limited to the original process's own folder of assemblies. In other words, it gives AppDomains' "load this folder of assemblies off to the side" behavior without the frustrating AppDomains quirks.

We defined the concept of a TestAssemblyLoadContext, the little pocket of assembly-loading necessary for one test assembly folder:

class TestAssemblyLoadContext : AssemblyLoadContext

{

readonly AssemblyDependencyResolver resolver;

public TestAssemblyLoadContext(string testAssemblyPath)

=> resolver = new AssemblyDependencyResolver(testAssemblyPath);

protected override Assembly? Load(AssemblyName assemblyName)

{

// Reuse the Fixie.dll already loaded in the containing process.

if (assemblyName.Name == "Fixie")

return null;

var assemblyPath = resolver.ResolveAssemblyToPath(assemblyName);

if (assemblyPath != null)

return LoadFromAssemblyPath(assemblyPath);

return null;

}

...

}Armed with this class, we can successfully load a test assembly and all its dependencies in a safe way and from the right folder. The test runner can work with the loaded Assembly directly, knowing that the loading effort won't pollute the test runner's own dependencies:

var assemblyName = new AssemblyName(Path.GetFileNameWithoutExtension(assemblyPath));

var testAssemblyLoadContext = new TestAssemblyLoadContext(assemblyPath);

var assembly = testAssemblyLoadContext.LoadFromAssemblyName(assemblyName);

// Use System.Reflection.* against `assembly` to find and run test methods...We've come full circle: The Fixie v3 Visual Studio plugin uses TestAssemblyLoadContext to load test assemblies in process, similar to the way the Fixie v1 plugin did with AppDomains. The core Fixie.dll assembly need only be loaded once. Most importantly, we got to eliminate all the interprocess communication while taking advantage of the best that the new circumstances allowed.

Always be designing

When you work with any long-lived system, some of your maintenance pains are really clues that outside circumstances have changed. If your circumstances are changing, take a step back and reconsider your design. Are you mistaking your solution for your requirements? Articulate your requirements separate from your solution, and see whether your circumstances suggest a new and perhaps even exciting direction.

2 Comments