Why did Plato argue that remixing should be banned by the state? What threats did jazz and rock 'n roll pose? And what does all of that mean for the conflicts between artists and copyright today?

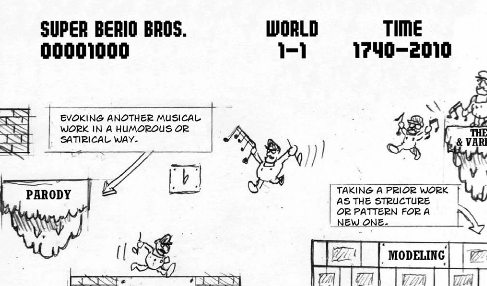

Those are the questions Jennifer Jenkins, James Boyle, and Keith Aoki answer in layman-friendly language in Theft! A History of Music, a graphic novel expected next spring. The three have a previous comic book, Bound by Law, which (like Theft!) attempts to translate complex legal concepts to make them accessible to a wider audience through a friendlier format.

Jenkins described the current state of things as the "music wars." We witness this as a battle between those pirating and remixing without authorization against the record companies that are resorting to legal means to try to sustain their increasingly obsolete business model. But according to Jenkins, "Research shows that both are inaccurate and ahistorical. The history of music can teach us a lot about today's debates."

And when she says history, she really means history. Her earliest example is Plato, who wrote in The Republic:

Music and gymnastic (must) be preserved in their original form, and no innovation made. They must do their utmost to maintain them intact. And when anyone says that mankind must regard...

The newest song which the singers have,

they will be afraid that he may be praising, not some new songs, but a new kind of song; and this ought not to be praised, or conceived to be the meaning of the poet;

for any musical innovation is full of danger in

the whole State, and ought to be prohibited.

Even 2000 years ago, people were already arguing about mashups.

"If you see music as a reflection of the order of the cosmos, as the Greeks did, or as a mode of communication that can jump the firewall of the brain and communicate directly to the emotions, then of course you would worry about the remix. Because the wrong results could be dramatic," Jenkins said.

But it was a cultural problem. Plato wasn't worried about property rights.

Skipping ahead a few centuries, in 1924, Etude magazine pondered the "jazz problem," by noting that, "Jazz is to real music what the caricature is to the portrait." The boundaries policed then were as much racial as they were musical. Similarly, a few decades later, the US had white segregationists who wanted rock 'n roll banned because they saw the inspiration and spillover from black R 'n B music.

Musical borrowing, which much music relies on, is similar to remixing, but it's much older than Nine Inch Nails. Brahm's first symphony was described by conductor Hans von Bülow as "Beethoven's Tenth" due to its similarity not just musically, but also in theme to Beethoven's work. Brahms interpreted this as a plagiarism accusation, when in reality he was well aware of the intentional similarities.

Click image to enlarge and view full comic.

Today we recognize many of these types of borrowing not as wrongdoing, but as art. Will the future be the same for sampling hip hop artists who are now sometimes seen as thieves? Or will we continue to suppress musical innovation with stricter regulation?

In parts two and three of this series, read about what happened when copyright came into the picture and what all of this means for the future of musical creativity.

Jenkins and her co-author and artist, James Boyle and Keith Aoki, expect to release Theft! A History of Music under a Creative Commons license in the spring or summer of 2011.

3 Comments