Our society and its lawmakers are notoriously bad at predicting the effects of new technologies. I think of the ongoing battles over new distribution formats, like the assumption that "the VCR [would be] to the American film producer and the American public as the Boston strangler is to the woman home alone." Jennifer Jenkins, one of the authors of Theft! A History of Music, has an even more basic and older example: musical notation.

Read part 1 of this series about the upcoming graphic novel Theft! A History of Music and the history it reviews. In part 3, we'll talk about what it all means for the future of music.

Ancient Greeks had their own system of notation as early as the sixth century BC, but it seems to have been used infrequently and fell out of use entirely around the time of the fall of the Roman Empire. Then, other than a few less notable efforts, musical notation wasn't reinvented for several centuries.

So why did the idea come up again? For sharing—but only a very specific type of sharing. The Holy Roman Empire wanted control and uniformity in their sacred church music. Until then, to ensure the standard form, they would have to send around a choir to disseminate the unified mass and song. Hardly practical. But with notation, the approved (and only the approved) tones, music, and chants could be more quickly spread.

Despite the goal of uniformity, however, the reality was that the invention helped people experiment and innovate, then preserve and transmit music—nearly the opposite of the empire's intention for control and conformity.

Unfortunately, we're not much better today at predicting the effects of significantly more advanced technology.

Our generation has a different relationship to musical culture from any other in history. We have the most opportunity for innovation and sharing, but also the most laws preventing it. So when did intellectual property law get its creativity-stifling fingers into music?

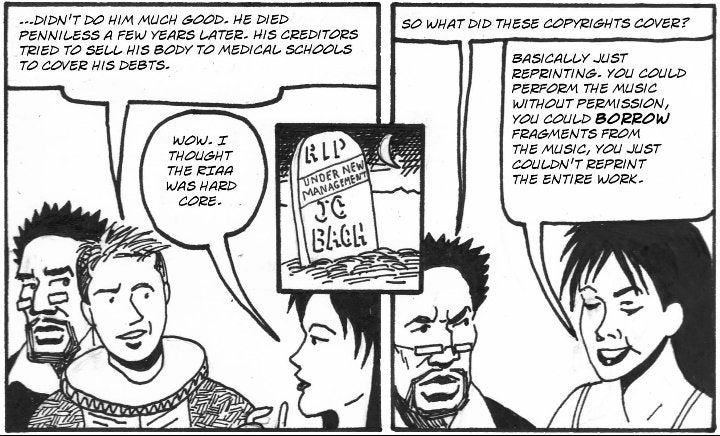

In 1710, the Statute of Anne, now seen as the first copyright law, went into effect and gave authors rights for the first time. But it wasn't applied to music until 1777, when Johann Christian Bach and Karl Friedrich Abel brought a case in which the court found that musical compositions counted as writings that could be covered under the statute. Nevertheless, you still needed permission only for entire works, not fragments, or for performance.

Jenkins pointed out that despite this victory, Bach died penniless, and his creditors tried to sell his body to medical schools. So he won the case, but in the long run, perhaps things could have gone better for him.

Click image to enlarge and view full comic.

Click image to enlarge and view full comic.

Skipping a few centuries again, Jenkins offered more modern examples. "Music has a long and rich history of borrowing across genres and subgenres," she said. "Take the blues, which draws from a rich commons. Or take rock 'n roll."

The law didn't interfere with those practices, for several reasons. Then things changed when digital sampling came along. Today musicians are told that they must license the tiniest fragments of sound, even though music has fundamentally relied on borrowing throughout history. What was once creation is now regarded as theft.

In 1991 an injunction was granted against Warner Bros. Records and Biz Markie for his sampling of Gilbert O'Sullivan's "Alone Again (Naturally)" in his own track titled "Alone Again" (Grand Upright Music, Ltd v. Warner Bros. Records Inc.). Jenkins pointed out that the decision quoted the Ten Commandments--"Thou shalt not steal"--but not copyright law.

In "100 Miles and Runnin'," the group N.W.A. sampled, lowered the pitch of, and looped a two-second guitar chord from Funkadelic's "Get Off Your Ass and Jam." Funkadelic sued, and the federal appeals court ruling over the 2005 case, Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Films Inc., said, "Get a license or do not sample. We do not see this as stifling creativity in any significant way." Quite the opposite is true, though. This ruling eliminated de minimis as it relates to sound recording copyright.

De minimis is the doctrine that means something is too minor, too trivial to care about. When the court was asked how much would count as de minimis, the answer was a single note—maybe. In a footnote, they wrote:

A question arises as to whether the copying of a single note would be actionable. Since that is not the fact situation in this case, we need not provide a definitive answer. We note, however, that under the Copyright Act, the sound recording must "result from the fixation of a series of musical, spoken, or other sounds ...." 17 U.S.C. § 101 (definition of "sound recording").

"What's happening?" Jenkins continued. "This level of granularity--licensing two or three notes--IP rights are being applied down to the atomic level of culture. Tiny fragments of music come loaded with demands for payment and copyright protection."

Despite the assertion that creativity is unaffected, these rulings have changed the music that we create and the way that it sounds.

Will it in any way give us more art, more creativity? Because after all, that's the purpose of copyright, which is defined in US law as "To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts." It doesn't seem so.

Would jazz, blues, rock, or soul have developed the same way under this legal regime? Probably not.

Jenkins and her co-author and artist, James Boyle and Keith Aoki, expect to release Theft! A History of Music under a Creative Commons license in the spring or summer of 2011.

Comments are closed.